The disability of deafness: How a cholesteatoma changed my life

Being deaf in one ear definitely has its advantages. When I was a kid, my mom would yell up the stairs to ask a favor or to assign a chore, which I was conveniently “unable” to hear due to my deafness. If I’m ever with someone who talks too much, I can simply sit or walk on their right side and face my left ear toward them. I can lie on my right side with my ear against the pillow and effectively shut out most sounds. Losing hearing in one ear can be convenient.

But while I can joke about being deaf in one ear and talk about the perks that accompany it, the story of how I became deaf is not so lighthearted. When I was six I took the standard 1st grade hearing test. You know, the one where you put the headphones on and lift your hand when you hear the beep? I failed that test and was told to see a doctor. Upon visiting the doctor, the second he looked in my left ear all color drained from his face. He looked at my mother, explained that I had a cholesteatoma, and that I would need emergency surgery within the week.

What is a cholesteatoma?

A cholesteatoma is an external cyst generated as a result of a developmental abnormality. A cholesteatoma can be acquired or congenital, with the acquired version being more common. In layman terms, a congenital cholesteatoma (which is what I had) develops because some cells that weren’t supposed to be in the ear became trapped there when the ear drum sealed during development, resulting in a tumor-like growth in the middle ear. A cholesteatoma can be especially dangerous because of the inner ear’s proximity to the brain. If the growth becomes too large, it will eventually eat into the bony structure separating ear and brain, resulting in possible brain damage and death. This is why the doctor’s face went pale when he was examining me. The growth had become so large that it was making my ear drum bulge. If surgery had not been performed, I would have died within a couple of years.

What are the symptoms of a cholesteatoma?

Symptoms typically include ear discharge, loss of hearing, blood coming from ears, a rotten smell, imbalance, and earache. Hearing loss and discharge are also symptoms of more common, less-threatening ear infections. However, since a cholesteatoma can be deadly, it is always considered a possibility when a patient has an earache. Only after concluding that the problem is only a common ear infection should a doctor exclude cholesteatomas.

Why do cholesteatomas affect hearing?

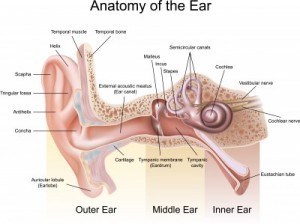

Cholesteatomas can eat away at the bones in the middle ear, namely, the malleus, stapes, and incus. Sound waves are mechanical, meaning that they vibrate, however so slightly, and the ear needs bones to register those vibrations. This is the most common side effect of cholesteatomas: loss of those three middle ear bones. Also, since the cholesteatoma is a growth, it is a mass interfering with the sound waves. In other words, stick some cotton balls in your ears and see how that affects your hearing.

I am, in fact, not completely deaf in my left ear. After finding the growth, the doctors promptly performed surgery and removed it. They discovered that I had lost both the malleus and the incus, but I had a portion of the stapes left, or rather a stub. The doctors laid my new ear drum (made of skin taken from the back of my leg) on top of the stub. It has been judged that I retain about 10% of the hearing that I should normally have in that ear. Essentially, I can stick an ear bud in my ear to listen to music, but anything farther away than that is difficult to hear.

What procedure is needed to remove a cholesteatoma?

Since a cholesteatoma grows in the middle and inner ear, it is difficult to remove via the ear canal. Although in some cases it can be removed by operating in the ear canal, a far more common practice is to make an incision behind the ear, pull the ear forward, and drill into the skull to reach the inner ear. The bottom line is that if you have a cholesteatoma, a procedure needs to be done because it can become life-threatening.

How do we cope with deafness?

Honestly, there isn’t much that can be done about deafness. Believe me, my doctors tried. I had my first surgery to remove the cholesteatoma when I was 6 years old and a second surgery to clear out scar tissue when I was 7. Removing the scar tissue did little to help my hearing, so the doctors then attempted three different surgeries to restore my hearing. All three tried something new, including inserting a prosthetic bone in my ear, and reconstructing my ear canal into an ear cavern. In the end none of them were successful. My doctor suggested hearing aids, but as a child about to go into middle school, I declined that idea.

The good news is that being deaf isn’t the end of the world. I have learned to adapt. I face my good ear toward a person that is talking to me. I use earphones when talking on the phone. I view my disease and recovery as a unique part of me that I like to share with people. I am proud to be deaf.

Ryan Wilson is a professional blogger and writer, and the current editor of Rusin Medical, a health blog committed to providing readers with current medical topics.