Sailing Backwards

We are passing the entrance to the Westport River along the edge of Buzzards Bay and Rhode Island Sound. An eighty degree day. The sails are full and water passes below as FactorX enters the harbor. Enormous glacial remnants of granite mark one side of the channel, a long white sand beach the other, both populated by children of all ages playing along the water’s edge. The winter hours lost to sanding, varnishing, and painting at once make sense as I practice the art of living in the moment.

“What’s that?” I ask as my wife’s voice stirs me from my daydream and causes me to refocus the angle of the tiller.

“We aren’t moving.”

I look down and confirm that the water is indeed rushing by the hull and I glance up at the sails, which are set full although the wind is light.

“Actually, I think we’re now going backwards,” Sally says with the reasoning of a seasoned sailor and extremely reliable observer.

My eyes scan down to the GPS. I assert, with the manly confidence of my gender, “We aren’t going backwards. We’re holding steady.”

Holding steady. Sounds so much better than not moving, don’t you think?

The tidal flow of the Westport River produces a significant current, especially where the channel narrows at the river’s mouth. In light air this challenge is compounded by those huge granite rocks that block the wind, enough so that light air conditions necessitates the use of the engine for all but the saltiest of sailors. I get the diesel going and propel us forward.

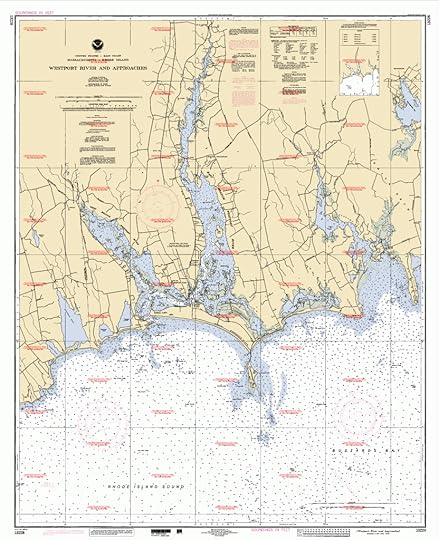

(Chart of the approach to the entrance to the Westport River)

Our movement is still slow against the current giving me ample time to think of the whaling ships that left this harbor in the mid 1800s. I suppose that back then, waiting for a favorable current wasn’t such a big deal. What’s a few idle hours when you’re about to spend the next two years at sea.

Today, sailors are aided by the Eldridge Tide & Pilot Book, which provides accurate predictions on ebbs, flows, and surges for areas all along the coast. By religiously referring to Eldridge you can speed your trip and avoid hours-long slogs against the current. In areas such as Wood’s Hole, the Cape Cod Canal or New York’s Hell’s Gate, use of Eldridge becomes a heightened catechism if you want to stay off the rocks.

Yet, as much as I try to keep a copy of Eldridge aboard, it’s not always easy to make needed time calculations while the tiller is in one hand and a sheet in the other. For this reason I was especially interested to learn of some current data available online or via a smartphone courtesy of the University of South Carolina. Check it out:

http://tbone.biol.sc.edu/tide/worldmap.html

There’s a wonderful passage in Farley Mowat’s classic book The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float that describes Mowat’s troublesome engine that would frequently operate only in reverse. Mowat describes how he departed a Canadian harbor backwards, his sails up and full but not able to overcome an engine that was cranking away in the wrong direction. Someday I might want to recreate that scene, but if I do, I want to do it intentionally (or at least have some basis for supporting that claim), so I’m going to spend some time testing-out this South Carolina computer database.

If you’re a sailor give it a look because sooner or later we all end up sailing backwards for some period of time, don’t we.

Share on Facebook