O Holy Knight

I love Paladins. As far as I can remember, I always have.

This is kinda crazy for a variety of reasons, not the least of which being my own personal views on spirituality and pacifism. Maybe that's one of the reasons I like the idea of a holy warrior so much. It is much easier to fight and die for what you believe in than to just die. That clarity of purpose is hard to come by in real life, which may make it so attractive in fiction.

At any rate, the turnkey moment for my paladin was was the realization that I appreciate paladins across cultures and genres. Sure, the love started with the very Dungeons & Dragons idea of a holy knight dispensing justice from the back of his white charger, but there are some other archetypes I didn't understand my own appreciation for until I tied them into the concept of the Paladin.

Obviously this is a pretty broad definition of paladin as "holy warrior," but I think that's fair considering how far away from The Song of Roland the D&D paladin is. I'm just widening the net similarly, but feel free to argue in the comments. Now, without further adieu, here's two of my most Eastern examples of paladins I love.

Sohei

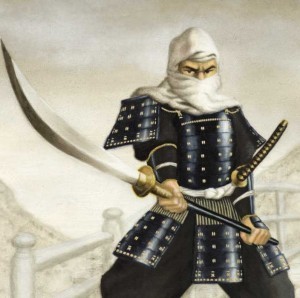

Sohei"Only three things disregard my wishes: the rushing waters of the Kamo river, the unpredictable dice, and the mountain priests."

-Emperor Shirakawa (1073-1086)

First off, just look at that bad ass! A masked samurai with a sword on the end of an eight foot pole! Shields and big horses aren't the only way to roll like a paladin.

Sohei were the military arm of Buddhist sects in Japan during at least the Sengoku and various Shogunates, especially Tokugawa. These guys are sorta the token example of "fighting for peace" and how relatively stupid a concept that is. But like all Japanese warriors, they made up for philosophical holes by being amazing fighters.

Sohei favored the naginata enough that the weapon has become traditionally synonymous with them. Part of their fame was the ability to spin the weapon so hard and so fast that no arrow would hit them. Otherwise, they armed themselves more or less like the samurai, often incorporating steel helms beneath their trademark white cowls.

"Temple samurai" is a pretty boss concept.

My favorite story about sohei shows that they were thinkers willing to use religious beliefs against their enemies just as deftly if not as often as they did their weapons. There is a tale of an intractable daimyo (lord of lands, akin to a duke) who simply refused to come to accord with the monks in the mountains near his capitol. Normally, the sohei would swarm down the mountain and fight the daimyo's forces. But this daimyo's capitol had grown over a trade crossroads, making the lord very powerful and very rich. This allowed him a standing army strong enough that such a fight would likely end badly for the monks even if they won the battle.

Instead of a massive force, a small cadre of sohei marched down the mountain bearing their shrine's idol, sort of a large, ornate box acting as a, for lack of a better term, Buddhist reliquary. They set it down at the crossroads of the daimyo's capitol, right in the middle of where the merchants conducted all their trade and business. They placed a curse upon the idol and walked back up the mountain.

For several weeks, the cursed idol crippled trade. Nobody wanted to go touch the thing. Most wouldn't even go near it. The daimyo found his brisk trade ground to a halt. He made accord with the monks, who promptly came down the mountain, de-cursed the idol, and took it back to the monastery.

Wudang Monks

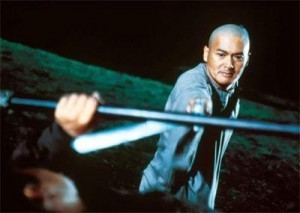

You know these guys best from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, starring the inimitable Chow Yun Fat (pictured right) and Michelle Yeoh.

You know these guys best from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, starring the inimitable Chow Yun Fat (pictured right) and Michelle Yeoh.

Wudang Monks were real, but their reputation as "holy warriors" is apparently largely fictitious. Since I'm not from ancient China, the fictitious reputation affects me way more than the historical reality. At their core, the Wudang monks are Taoist counterparts to the Buddhist Shaolin (or vice versa) named for the mountain housing their monastery.

On a basic level, they're "Chinese sohei," but they diverge in a few big ways that make them different enough to appeal to me in other ways.

First, they didn't typically go to war, which means no vast armis of Wudang monks. In fiction, the Wudang typically ran in singles or duos, although they would team up with larger groups of non-monks.

Second, and the reason they didn't go to war, is that Wudan monks fought primarily for justice. In a vast land with little access to anything like a modern day police force, an expertly trained fighter who wished for nothing but seeing justice done and stood outside the social order of wealth and privilege would have been an absolute godsend (see what I did there?) to peasant villagers. That's a recognizably paladin idea applied in a very Eastern way.

Third, they retained their unassuming, monkish look. Sohei wore the cowls so that nobody ever forgot that a monk stood beneath all that armor and weaponry. The Wudang wanted to be recognized as monks first and only, they just happened to be really amazing swordsmen as well. No stallions, no big armor, no piles of weapons. This is absolutely a paladin focused through an Eastern mindset.

Lastly, the fictional Wudang are the sorta inspiration for the Staten Island rap supergroup, Wu-Tang Clan.

Okay, this post has gone on longer than I expected. In the near future, I'll probably talk in more detail about the original, Western paladins. I'll suggest the best novel about a paladin (until I write my own, that is). I'll also discuss the difference between a cleric and a paladin in roleplaying game terms since D&D had made that a conversation almost necessary if you're going to write or game in the fantasy genre.