Doctor Jekyll and Mister Amygdala

A friend just wrote to me with a troubling story. He’s had a few upheavals in his life recently, including a divorce, but then he made a dreadful ethical slip and got involved with a former patient of his. Of course that’s a huge ethical no-no in the caring professions, and it may have life-long consequences for his career.

A friend just wrote to me with a troubling story. He’s had a few upheavals in his life recently, including a divorce, but then he made a dreadful ethical slip and got involved with a former patient of his. Of course that’s a huge ethical no-no in the caring professions, and it may have life-long consequences for his career.

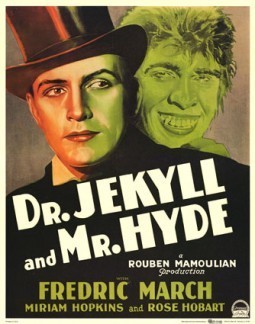

But in responding to my friend’s letter I was reminded of Robert Louis Stevenson’s story, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Most of you know this story from cheesy horror movies, but the book is actually an astute spiritual parable that sprang directly from Stevenson’s subconscious in the form of a nightmare. The story stands up psychologically to the point where you can translate the characters into the terms of modern neuropsychology as represented by the work of author Wildmind contributor Rick Hanson, Ph.D.

Dramatis Personae

Dr. Jekyll, who is the neocortex and mammalian brain, responsible for self-monitoring, planning, advanced cognition, empathy, and compassion.

Mr. Hyde, who is the “reptilian” part of the brain, concerned with fight, flight, and fulfilling appetites.

The Story

Henry Jekyll is a good doctor who helps many people through his work. He has a well-developed mammalian brain in which empathy and compassion are important. He is, however, deeply troubled by his amygdala-driven unexpressed bad-boy tendencies within. He is ashamed of them and afraid of them.

We all have “hindrances” — potentially destructive tendencies toward craving, hatred, and fear. Those tendencies manifest in our thoughts and our actions.

One thing all meditation teachers have to do is to let people know that it’s OK to have these hindrances. When people start self-monitoring (a neocortical activity), as they do when cultivating mindfulness, they start noticing distracted, craving, hateful thoughts. And their reaction is often to get upset about these. But that’s unhelpful, because that’s a case of responding to a hindrance with yet another hindrance. Yes, ultimately we want to get rid of the hindrances, but you can’t deal with them on their own terms, by getting angry about getting angry, or craving a lack of craving, or being afraid of being afraid, or getting despondent about noticing despondency.

These hindrances are not “bad.” They are actually mental behaviors that have evolved over millions of years in order to protect us. Someone threatens you, you get angry, they run away (hopefully). A big carnivore jumps out in front of you, you get scared, you run away. You see something you want, you grab it. And so forth. But these tendencies, while they work well in wolf-packs and worked well when we lived in caves, are maladapted for life in the modern world. Being angry with your computer when it’s working too slowly doesn’t change the computer, and just makes you unhappy and even ill. Bingeing on food because you want it can make us ill in different ways. Negative emotions undermine our relationships with others, so there’s a social cost. And even when they don’t have social or health drawbacks, our hindrances make us unhappy. Our sense of well-being is sub-optimal when we’re frustrated, or craving, or anxious.

The hindrances are not bad, they’re just strategies for finding security and wellbeing that happen not to work very well.

Dr. Jekyll is the man who sees these potentially destructive activities going on, but who is afraid of them. He’s the neocortex observing the amygdala. He identifies with his goodness, and psychologically disowns his hindrances. And he represses them. But in doing so, he’s acting out — internally — a form of violence driven by fear. The neocortex has been silently hijacked by the amygdala, since this fear actually stems from primitive, reptilian parts of the brain.

So Jekyll creates a drug that will anesthetize the bad boy within. He’s trying to anesthetize the amygdala, so that his neocortex no longer has to keep his “baser” instincts in check. But what he hasn’t realized is that over the years of repression, the bad boy has become much stronger. The repression Jekyll has done over the years is a form of inner violence, and thus has been feeding Hyde. And when Jekyll takes the potion it’s his good side (the neocortex, in modern terms) that goes offline, and the inner bad-boy (the reptile brain, the amygdala) that dominates. Mr. Edward Hyde is released. And it ain’t a pretty sight.

Once Hyde — a destructive monster who delights in violence and in indulging his unseemly appetites — is released, it’s impossible to keep him restrained. He becomes stronger with each outing. And indeed, when parts of the brain are exercised, the wiring in them becomes stronger. That part of the brain actually grows.

Of course the story doesn’t end well, and Jekyll is destroyed, but it’s a cautionary tale that we’re meant to learn from. So what should be learn?

What Jekyll should have done is to strengthen the neocortex by developing more mindfulness and compassion, so that the amygdala-driven Hyde would be known, contained without being repressed, and simply fade away through atrophy.

Easy to say! Let’s break that down a little.

When we stop reacting to the hindrances, and either simply accept them without acting on them, or cultivate their opposites — qualities of love, confidence, etc. — the neocortex actually grows. That part of the brain becomes thicker. The number of connections running back to the amygdala increases, so that the reassuring signals reaching it (“It’s OK. There’s no need to panic and get violent. I have this covered”) are stronger. And the amygdala actually shrinks. The brain is a real energy-hog, and takes a lot of work to maintain. If our fight-or-flight mechanisms are not needed, then the body somehow knows that it’s time to remove some of the brain circuitry necessary for those mechanisms.

So Dr. Jekyll is not conquered through fear and repression. He’s conquered through mindfulness and compassion.

It’s worth mentioning that this process of dealing skillfully with hindrances can be short-circuited by “spiritualizing” them. All those spiritual teachers who turn out to have been living double lives, giving inspiring teachings while sleeping with their students? Usually they’ve been telling themselves, and their partners, stories about how the relationships are “sacred” or an expression of non-duality. This is just another example of the amygdala hijacking the neocortex. The old way was, you want, you take. In a spiritual context you want. You make up a half-way convincing story. You take.

This reminds us that Mr. Hyde is sneaky. We need to give the neocortical Dr. Jekyll a lot of exercise, through practicing mindfulness and compassion. And we also need other people to give us feedback and to call us on our bullshit. We need sanghas. Getting enlightened is a team sport.