Myth Merchants, Calcutta Times, Aug 11, 2012

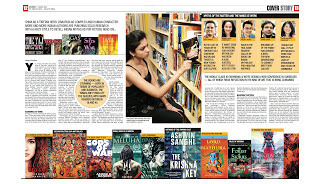

SHIVA AS A TIBETAN HERO, DRAUPADI AS COMPLEX AND HUMAN CHARACTER. MORE AND MORE INDIAN AUTHORS ARE PUNCHING SOLID RESEARCH WITH A RACY STYLE TO RETELL INDIAN MYTHS AS POP FICTION. READ ON...By Dibyajyoti Chaudhuri, Calcutta Times You could call them the charioteers of the gods. Armed with solid research, a vivid imagination and a gripping writing style, a host of authors is dipping into the vast pool of Indian mythology to come up with powerful tales — and takes — that retell our social and historical origins. So you have Amish Tripathi showing Shiva as a Tibetan hero who migrates and attains divinity in a distant land. Ashok K Banker reinvents Sita, Ravan and Ram in his Ramayana series, while Devdutt Pattanaik deconstructs some of our myths and legends in his Myth=Mithya. Ashwin Sanghi, Manreet Sodhi Someshwar, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni... the list of authors reworking age-old stories is growing longer. The results are often stunning — both in terms of popularity and business. The tomes are flying off the shelves, with many readers in the 18-40 age group. Amish, whose Shiva series has been a runaway hit, says his books have generated retail sales worth 17 crore. Ashok, who has seen the market for such books grow over the years, says his books have sold 1.4 million copies till now. So what is it that’s drawing the XBox generation? “There are some crucial reasons for this. You see, in Greece or Egypt, no one talks about Zeus or Amun Ra. But Indian mythology surrounding Ram, Krishna or Shiva is very much alive in the Indian mind. They have become a part of our collective consciousness,” says Amish, who also sees economic factors at play. “In the last 20 years, we’ve emerged as an economically confident nation and there’s a newfound interest in our culture. I’d say we’re at the right place at the right time.” Author Ashwin Sanghi feels a change in demography has a lot to do with the popularity of mythology. “Tales of Ramayana and Mahabharata were traditionally conveyed by elders in the family to youngsters. Breaking up of the family structure and the Indian diaspora spreading far and wide has created a need for the new generations to connect with their culture. A modern format of retelling the stories is important for this generation. The retelling has led to the blurring of lines between mythology and history,” he says. Bookstore owners feel that the racy, new-age storytelling style of these authors helps. “We all knew these characters, but they have been retold and mythical figures have been humanized. These novels are popular across the board,” says Gautam Jatia, CEO of Starmark. The designs, too, are in sync with the smart writing. Rashmi Pusalkar, who’s designed Amish’s covers, says, “Shiva is a human of flesh and blood, he is not a god. The challenge was to show him as vulnerable. I portrayed him from the back, because Indian gods are never seen from the back. He has battle scars and a sculpted physique.” Gunjan Ahlawat, the designer for Ashwin Sanghi’s upcoming The Krishna Key, talks about using fonts and typography that connects with the youth. Says Jadavpur University student Sabyasachi Chaudhuri. “You feel good the moment you hold these books. Flashy covers, smart prints — you feel like grabbing a copy,” he says. The genesis of the trend goes back to the ’90s, when Ashok K Banker came up with his Ramayana series. “Back then, some saw it as pro-Hindutva writing. However, there was a huge pool of great stories, never published before for new-age readers. Modern storytelling had become obsessed with the self; this new genre was a break from that. Now, other writers have found success in this genre,” he says. Author Manreet Sodhi Someshwar, whose Taj Conspiracy has been a big hit, is still a bit cynical. “The immense success of some recent books — the Meluha trilogy for instance — might give the impression that re-inventing Indian history/mythology has been a huge success, but it could also be a fad. I guess we’ll have to wait and see how the genre grows. However, one big change is that earlier what sold in India was primarily literary fiction which had been endorsed by the West. But, of late, Indian fiction has burgeoned and we now have a wide range of writings by Indian authors. Hitherto unexplored genres have also opened up,” she says. Can we call this retelling of our legends pulp mythology? Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni reacts sharply to the term. “I would definitely not call this pulp mythology, a term which implies a lack of seriousness and commercialization. My Palace of Illusions — which shows Draupadi as a complex, human character — as well as other books on Indian mythology are based on careful, thoughtful and sometimes risky reconstructions. They follow in the footsteps of centuries old re-imaginings such as the Kambha Ramayana, the Ramcharitamanasa and the versions of Krittibas and Kashidas,” Chitra says. Manreet agrees with Amish and feels that as the Indian economy is growing, the middle class is expanding and we are seeing a new confidence in ourselves — all of which finds reflection in the kind of art that is being consumed now. “New writers don’t feel the compulsion to write for a Western market because the domestic market is sufficiently robust and is showing a demand for local stories, set within Indian locales and Indian history,” she says. Siddharth Pansari, franchise owner of Crossword bookstore, feels if there were just a handful of Indian authors before, there are now thousands. “Da Vinci Code was a huge hit, although it was set in the backdrop of the Vatican. It is natural that such a book set in an Indian backdrop will do well. Which is why stories dealing with our indigenous myths have so many takers,” he says. Schoolteacher Paromita Dutta couldn’t agree more. “Many of us have not read the Ramayana or Mahabharata in the original form. These re-telling of ancient stories are simply great,” Paromita says. But is a country that is sensitive about its religious and cultural sentiment a good place to experiment with the gods? “What is true mythology? The creation myths in Shiva Purana and Brahma Purana are different. Which one do we believe? The Kambha Ramayana and Ramacharitamanasa are different from the Valmiki Ramayana. There is a lovely line in the Rig Veda which perhaps sums it up nicely. ‘Ekam sat, viprah bahuda vadanti’. Truth is one, wise men speak it differently,” says Amish. Amen to that.

Published on June 15, 2012 06:29

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Please break down the articles in to paras for the ease of reading