Who Do You Write For? Are we simply producers of product? Can I get a refund?

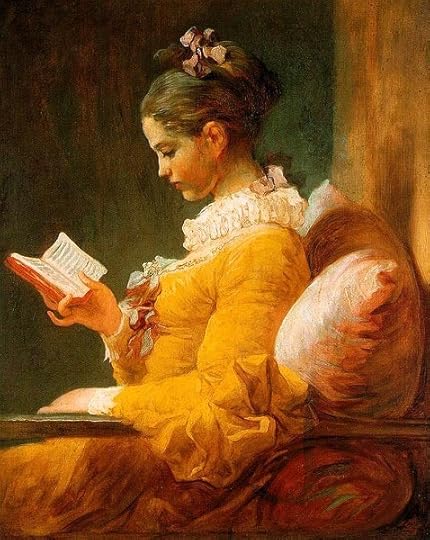

THE READER, by Fragonard, 1732-1806

This question should haunt every writer. Certainly, there is no writing course in the world that doesn’t confront students with it. It seems like an easy one to answer, but it has levels of complexity that, for the most part, only get discussed within their own, embattled spheres.

There is, philosophically, the overarching issue of the writer-text-reader relationship. The obligations of a writer to their readership was examined in many ways over the 20th Century. By the Aestheticists, all the way to the Post-Modernists, it has been a thoroughly chewed subject. I don’t want to list all the various theories – but here’s a good starting place if you’re interested.

Then, of course, there is the commercial sphere. It’s been important, in recent years to proclaim loudly and passionately that you write for your reading audience. It conforms well with the concept of fiction as ‘product’ and writers as ‘manufacturers’ who supply their ‘customers’ with the products they need.

But beyond all that, there is the very personal, very pragmatic reality for most writers of balancing genre expectations with their own creative impulses. And here, one can only speak for oneself. Looking back at the answers given by the writers who generously participated in my Other Voices, Other Genres series, it becomes clear that many writers write for themselves first. And this makes sense. We’re also the ‘first’ reader of any given work.

I spent a lot of time in the theoretical sphere, absorbing various understandings of ‘audience’ and ‘writerly’ reading and ‘open textedness’. And although I learned a lot, it has never been knowledge I could absorb and apply fully as a writer. Admittedly, both Barthes and Eco have had a very strong influence on the way I began to conceive of my ‘reader’. But when I actually sit down to write, I don’t consciously keep that theoretical understanding at the forefront of my mind. I do suspect, however, that it has subtly informed how I ‘address’ the reader in my writing.

I find the second sphere simplistic and degrading. I don’t think there is anything wrong with selling books or appealing to an audience, but I’m disturbed by the spectre of such a transactional relationship between reader and text. It is a model that benefits the retailers at the expense of both readers and writers. My relationship with the books and writers I have loved was far more nuanced and equitable than a ‘buyer & seller’ association. As much as I do believe that the reader plays an integral part in how any give story comes alive, I do acknowledge that the dialogue has been initiated with the writer’s proposition of a story. I prefer to envision the relationship as a cooperative one, a mutual journey. A purely commercial model doesn’t allow for that power distribution. When I put myself, as a reader, into a writer’s hands, I need to trust them. I can’t do that if I believe that the other party is only doing this for money. And, conversely, if I want to take a fictional journey somewhere I have never been before, I cannot demand that the writer deliver my laundry list of literary expectations.

Like any reader, I want to be surprised, but I don’t want to be disappointed. But I can’t be surprised without taking the risk of being disappointed. I have noticed that there has been a steady trend towards readers who would rather simply revisit the familiar than be disappointed. It was really hammered home to me when, after giving a book a very low rating on audible, I got a message from them asking if I’d like to return the book and get my money back.

That really shocked me. There was nothing technically wrong with the file. I simply didn’t LIKE the book. I didn’t warm to the character, the plot didn’t engage me. Why would I want my money back? I took a chance, and I was disappointed. But that doesn’t mean the writer doesn’t deserve to be paid for their book. It simply wasn’t my cup of tea and I won’t be looking for more books from that author. It wasn’t a matter of a mistaken purchase. or an inferior product. It was just a relationship that didn’t work out. You don’t want your money back. You learn and move on.

It did occur to me to wonder, though, why it is that, when the purchase of a book represented a significant outlay of money, both readers and writers have a far more respectful and valued view of each other. Could it be that the $2.99 e-novel has resulted in a $2.99 appreciation for storytelling? It seems a common problem with humans that we seem to value what we pay the most for, and have little respect for what we can purchase cheap or get free. I’m not suggesting we should go back to the days of ‘authorial worship’. But a middle ground might be found, no?

On a personal level, as a writer of stories, I try to write the prose that pleases me. I try to write stories I find interesting and characters who I find compelling. And, I guess, I rely on the fact that there will be readers out there who share my aesthetic. But I’m not willing, as a writer, to put the emotion and craft into my writing for someone whose only expectation is to have a good wank.

My recent interchange on the Guardian Books Blog elicited some interesting commentary: I found this one particularly interesting:

tkmarnell

2 August 2012 10:00PM

Wow, so much hullaballoo over a single sentence, which I didn’t even notice because I skipped the laundry list of titles and prices.

Here’s my take on erotica: its purpose is to titillate. The Google definition (by no means official, but generally representative of popular understanding) is, “Literature or art intended to arouse sexual desire.” If your purpose is not to arouse, but to explore the complications and implications of human mating behavior, it is not erotica. It is a story that happens to have sex…maybe a lot of it. Sex is not such a unique subject that every story that features it is automatically erotica, though nervous booksellers will lump it all together to avoid offending perpetually alarmed parents.

Now, you can’t deny that people who seek out straight-up erotica are looking to be aroused. Do you really think they’re there for the plot and prose, or complex discussions of how the social condemnation of desire impacts the modern man’s psychological makeup? They’re there for the rush. The endorphins. The emotional and physical high of the fantasy. Most don’t even care for the characters; a “he” and “she” will suffice for the purpose (or a “he” and “he,” or “she” and “she,” or two “shes” and a “he” with a cat watching from the doorway…). Conflict in these stories is not an avenue for private reflection and growth, but to build tension that makes the final release more satisfying. Ultimately, no, you don’t need to know the plot; it’s just the framework for the experience readers are after. You could say this about any book, really.

Erotica is what it is. It’s silly to try to justify it in terms of the genres detractors consider more “worthy.” By getting offended by the label of “porn” and insisting that erotica isn’t really about arousal, but all those things that great literary works are “supposed” to be about, you’re essentially agreeing that arousal isn’t a good enough goal on its own. What, exactly, is wrong with porn? Is it too base and obscene for the folks who write “quality” erotica? The message is so mixed it’s making my head spin.(Comment, “Ebooks round up: Fifty Shades of Erotica” Guardian Website, August 1, 2012, http://gu.com/p/39ecm)

What I was being told, if I’m reading this correctly, is that I should shut up and simply write stuff she can get off to, and drop any pretenses of skill, or plot, or characterization. She wants erotica to be porn. She wants erotica writers who believe there is a difference to shut up and put out.

Porn is a different genre of writing. Porn doesn’t require or even benefit from conflict. It doesn’t require characters, it requires stand-ins for the reader to step into and fantasize being. It only requires plot inasmuch as the sexual response could be charted as having a sort of three-act story structure. Writing good porn requires considerable skill. I have tried it and, frankly, I suck at it. You need to really understand that what you’re writing is a roleplay guideline for the reader. No matter what POV it is written in, should have the aura of 2nd Person POV haunting it. It is incredibly open-texted, a guided sexual fantasy experience. And anyone who thinks that is easy to pull off is nuts.

I maintain that erotica/ erotic fiction is different from porn. I know a that there are many erotica writers who disagree with me. I think there are a number of reasons for this.

There is the re-appropriation camp who feel that sexually explicit material of any type should be considered without value judgement. Although I agree with them politically, I do not feel, compelled, as a writer to represent that in my fiction. I’m a writer, not a social activist. Their stance is that if I won’t say that what I write is porn, then I’m saying porn is bad. No. I’m saying I am not skilled at writing porn, and taking a reader to orgasm is not the main motivation behind why I write or what I write. I am a piss poor producer of porn.

Second, there is a reactionary mainstream belief that porn is bad, but erotica is okay. Consequently there are a lot really good porn writers who call themselves erotica writers because their readers don’t like to admit what they’re after is porn. Erotica is ladylike, porn is for perverts. It’s kind of the opposite of the first camp.

What I see is that most erotic fiction writers get caught in the middle. They’re trying to craft a type of fiction that uses desire as a lens through which to tell a wider story. They write about characters whose conflicts are at least partially brought about by their desires, or are coloured by them. Sex, in erotic fiction, is contextualized within the lives and experiences of the character. It informs their definitions of self, and flavours their interactions with other characters in the story. But there has to be a story. There has to be conflict. Otherwise, it’s not erotic fiction.

All this has really led to me forming a much stronger picture of who I write for. I acknowledge that I don’t just write for myself. I do have a reader in mind when I write. It’s a reader who is interested in human complexity, a person who wants to be aroused, but on a less genital and more emotional level. And that requires that the eroticism is contextualized within a story form.

tkmarnell may be right. Perhaps when we speak of D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Anais Nin, Nabokov, etc, we should no longer use the term erotic fiction. Maybe the definition has changed. Maybe is has become a canon with no home.

But the problem with that is that, for literally 90% of my readers, I am an erotic fiction writer. The vast majority of my stories have sex and sexual desire at the very core of the story. It plays a pivotal role in plot and the narrative voice. So I’m not willing to agree with the commenter. I think she really just wants porn, and I don’t think most erotica writers write it.