Despotism, Distraction, and the Defense of Civilization

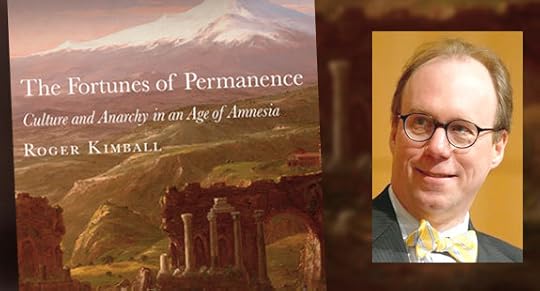

An interview with author Roger Kimball about his new book, The Fortunes of Permanence: Culture and Anarchy in an Age of Amnesia

Roger Kimball is Editor and Publisher of The New Criterion and President and Publisher of Encounter Books. He is an art critic for National Review and writes a regular column for PJ Media at Roger’s Rules. He has written and edited several books on art, literature, culture, politics, and education. He recently spoke with Catholic World Report about his most recent book, The Fortunes of Permanence: Culture and Anarchy in an Age of Amnesia, published by St. Augustine's Press, offering his thoughts on relativism, tyranny, culture, religion, Chesterton, art and architecture, socialism, and the future of Western civilization.

Catholic World Report: In the Preface, you write that the "embrace of relativism was a harbinger, a symptom of a seismic shift in the way people view the world." What was that seismic shift? And how did it set the stage, so to speak, for the rise and growing acceptance of relativism?

Kimball: Perhaps the best way of identifying the nature of that shift is to quote Dostoyevsky’s famous observation, from The Brothers Karamazov, that “If there is no God, everything is permitted.” Dostoyevsky’s great insight was to see that without allegiance to the transcendent, our parochial attachments are anchorless, and, being anchorless, they tend to drift along whichever way the current of sentiment pushes them. As I note in Fortunes, relativism, whether or not it travels under that particular name, has more and more assumed the status of a civil religion in the West. It bearing the promise of liberation from old pieties—just think back to the rancid jubilations of the 1960s and 1970s if you want an example—but regularly delivers new forms of tyranny and enslavement.

That’s to say, while the first upsurge of relativism can be an intoxicating draught—think again of the giddiness that ushered in the Sixties—the unpleasant hangover, the foundering on the jagged shoals of reality—is not long in coming. What seemed like a welcome liberation soon reveals itself as a vertiginous exile. Which is to say that, at bottom, relativism is a religious problem. “God is dead,” Nietzsche proclaimed in the 1880s. What he observed was an emotional, not an historical, fact. The unspoken allegiance to something transcending the vicissitudes of human desire had been (among the elites, anyway) shattered. The result was nihilism, that existential vacuum which human nature abhors and rushes to fill with a panoply of brazen idols and false gods.

Catholic World Report: An interconnecting theme in the book is how relativism informs a number of modern impulses and trends, including those of tyranny, utopianism, and benevolence. Many people, it is safe to say, think those three have little or no connection at all to one another. How are they connected? Why do many people fail to see the relationship between them?

Carl E. Olson's Blog

- Carl E. Olson's profile

- 20 followers