IF ROMEO AND JULIET GOT MARRIED

THE WOMAN BEHIND LOVE'S GREATEST MONUMENT

Colin Falconer

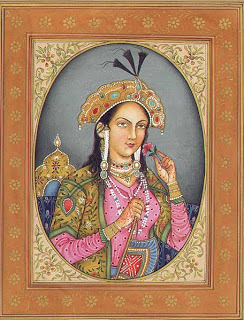

Mumtaz Mahal

In the west we think of Romeo and Juliet as the archetypal lovers, the

ultimate romantic couple. Yet India has perhaps better claim to the accolade

than Italy; if you want to find a monument to the world's greatest love story, you will

find it in one of India’s most polluted and industrialized cities, not the cobbled

medieval streets of Verona.

India’s Juliet was born Arjumand

Banu Begum, in Agra, northern India, the niece of the Empress Nur Jehan, wife

of the Emperor Jehangir. She was fourteen years old when she was engaged to

Prince Khurram - later to become the Shah Jahan. But she had to wait five years

for the marriage, for a date chosen by court astrologers as propitious for a

happy marriage.

For once, the court

astrologers got it exactly right.

In the intervening years the Shah had already taken two other wives; but after he married Arjumand he was so taken with her that he surrendered

his polygamous rights to other women in order to be only with her. He later

conferred upon her the title ‘Mumtaz Mahal’ - the chosen one of the palace.

According to the official court chronicler, Motamid Khan, the relationship

with his other wives ‘had nothing more than the status of marriage. The

intimacy, deep affection, attention and favour which His Majesty had for the

Cradle of Excellence (Mumtaz) exceeded by a thousand times what he felt for any

other.’

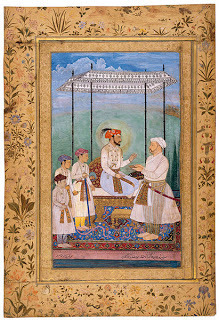

Of course, the affections of princes can be notoriously fickle; but not in the case of

Shah Jahan.

Mumtaz became his trusted companion, and travelled with him everywhere, even

on military campaigns, despite her frequent pregnancies. Court historians go to elaborate lengths to document the

intense and erotic relationship the couple enjoyed. His trust in her was so profound

that he even gave her his imperial seal, the Murh Uzah.

Burhanpur: photograph Md iet

In their nineteen years of marriage she bore him thirteen children, seven of

whom died at birth or at a very young age. But in 1631, while him accompanying on a

military expedition in Burhanpur (now in Madhya Pradesh) she died while giving

birth to their fourteenth child, a daughter named Gauhara.

The Shah was reportedly inconsolable. He went into secluded mourning for a

year and when he appeared again, his hair had turned white.

The first half of his life had been dedicated to their marriage; the second

half of it he dedicated to her memorial.

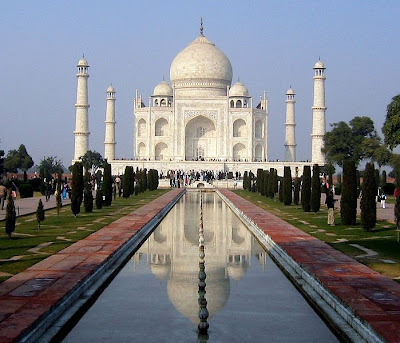

In 1631 he had

her body disinterred and transported in a golden casket back to Agra. He then set to work planning

the design and construction of a suitable mausoleum and funerary garden for the woman who was the love of his life. It was

a task that would take more than 22 years to complete: he was

still laboring over her tomb in his fifties.

the Taj Mahal

He had translucent white

marble brought from Rajasthan; jade and crystal from China; turquoise from Tibet;

carnelian from Arabia. He brought in the finest artisans in the Empire.

There were sculptors from Bukhara, calligraphers from Syria and Persia,

stonecutters from Baluchistan.

When it was finished it became one of the wonders of the world and remains the

iconic

emblem of India; the Taj Mahal.

But the construction bankrupted the Empire and soon after its completion, he

was deposed by his son Aurangzeb and put under house arrest at nearby Agra

Fort.

It is said that he could not see the Taj from his cell so he hung a

crystal in the high window so he could see its reflection there. When he died, Aurangzeb

buried him in the mausoleum next to his wife.

Theirs

was one of the great love stories of history. And as the four million tourists

who flock to Agra every year will attest, it was indeed a love that did not grow old.

See Colin Falconer's HAREM here.

See more history at

Looking for Mr Goodstory here.

I LOVE COMMENTS

From History and Women

Published on July 26, 2012 18:18

No comments have been added yet.