‘Shadow Years’ is a must read as voters sort out Romney’s conflicting narratives.

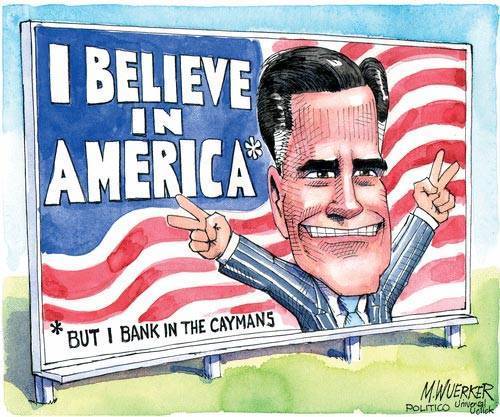

If we examine the achievements that Romney says qualify him to lead our economy, two things are certain: He generated great returns for investors but job creation was never a goal; and his success was dependent on a financial system designed and manipulated by powerful special interests.

David Bernstein’s article on the ‘Shadow Years’ is a must read as voters struggle to sort out the conflicting narratives about Romney’s corporate and political career.

From The Boston Phoenix

Romney’s Shadow Years

Mitt wants to make his departure for the Olympics a clean break from his business life — but it’s not that simple

By DAVID S. BERNSTEIN

With just six weeks to go before the Republican National Convention, Mitt Romney’s campaign has bogged down over the seemingly insignificant minutia of how to precisely define the leave of absence he took from Bain Capital, while he ran the Winter Olympics from 1999 to 2002.

It was predictable that this issue would arise — it has cropped up periodically virtually from the moment Romney returned from Salt Lake City in 2002, to run for governor of Massachusetts.

What may seem surprising is the intensity with which the Obama campaign is pressing its side of the argument: that Romney is responsible for Bain’s actions during those years. Equally noteworthy is the tenacity with which the Romney campaign is fighting back. Romney even submitted himself to five network-television interviews this past Friday, in a mostly unsuccessful attempt to quell the dispute.

The battle over these Bain “Shadow Years” looks especially odd, since the basic facts are not in much dispute.

When Romney left for the Olympics in February 1999, he removed himself from the day-to-day operations of the company. But he did not legally extricate himself at that time, remaining full owner of Bain Capital and most of its related entities, as well as president and CEO.

That only changed more than two years later, when he decided not to return to Bain after the Olympics.

Nobody claims that Romney was running Bain Capital’s day-to-day business from Utah; nobody can dispute that he was legally the head of the company at the time, and at the very least signed occasional documents in that role.

The devil is in the details. Did Romney truly have no input during that time, as he and the company insist? Or, did he keep a hand in the business, as many suspect?

That hardly seems like a huge matter of debate in a presidential contest. It’s not as if Bain Capital operated so much differently during those Shadow Years than it did while Romney was there in person. Romney has not even indicated that he would have done much of anything different had he been in charge at the time.

So why are both camps acting as though the election hangs in the balance?

The answer lies in the dual view Americans hold of corporate magnates.

For the most part, Americans respect supremely successful business leaders. We admire their skill, wisdom, hard work, and risk-taking; gobble up their memoirs and how-to books; and turn to them for analysis and insight.

But it’s a different story when the curtain draws back to reveal tales of greed, manipulation, and double-dealing. Then, America’s populist anger turns against those corporate titans. Think of cigarette executives who swear ignorance of their product’s harm; oil and energy executives whose shortcuts befoul the land while they rake in astronomical profits; business executives, like those at Enron, who rig the system while screwing over employees and customers; and bailed-out bank executives rolling around in multi-million-dollar bonuses.

A close election could easily turn on which of these two images captures the American electorate, as they consider handing the country over to Romney.

NO-LOSE LIFE

The “retroactive retirement” Romney finalized with Bain Capital, in 2002, claimed February 1999 as his exit date. For three years, Romney got to enjoy the perks of being the boss, including an annual salary of at least $100,000, as well as investment opportunities, and, presumably, the authority to intercede in Bain deals if he chose to, whether or not he actually exercised that power. He also held open the option of returning as boss and owner after the Olympics, if he wanted to.

He got all of that, while being absolved in the end of all responsibility and blame for anything the company did during that time.

The ability to fashion that kind of no-lose arrangement, frankly, is one way that the very wealthy and powerful differ from the rest of us. When revealed, it can make successes look inevitable, rather than impressive.

If Romney’s history of stacking the deck is subject to scrutiny, it could undermine the accomplishments at the core of the argument for his candidacy.

Bain Capital, for instance, often structured its deals as no-lose propositions: Bain extracted enormous fees and contracts from its takeover targets, making millions even when those companies collapsed.

And Romney has applied the principle to his own carefully guarded personal image for decades.

One of the most blatant was his pre-arranged face-saving plan when he agreed to head Bain Capital in the first place, in 1983.

In a tale first revealed by Boston Globe reporters in 2007, Romney agreed to do it only if his boss at Bain & Company, William Bain, ensured that there was, in Bain’s words, “no professional or financial risk.”

If Bain Capital failed, Romney would reclaim his old job and salary, plus any raises he would have received. Plus, Bain agreed to “craft a cover story,” the Globe wrote, to shield Romney from personal blame for Bain Capital’s failure.

It seems very likely that this is more-or-less how Romney arranged his leave of absence for the Olympics. It makes for curious bookends to his career at Bain Capital: he started by pre-arranging a way to avoid responsibility, and ended by retroactively arranging to avoid responsibility.

If so, it doesn’t make Romney sound like the bold turnaround master he claims to be. And it raises the question: what else in his life is as he claims, and what is just a pre-arranged “cover story”?

The secrecy and deception make it hard for voters to judge how much credit — or blame — Romney really deserves for Bain, or the Olympics, or his time as governor. It also suggests that a Romney presidency would be even more opaque than most.

COMPLICATED BUSINESS

The Shadow Years loom large with Romney because they fall within a time when his investment activity was particularly complex and wide-ranging — and open to criticism.

In earlier years — when both the leveraged buyout field, and Bain Capital itself, were newly developing, Bain Capital tended to get involved in fewer, fairly straightforward deals.

And after 2002, Romney placed his investments in a blind trust prior to taking the oath of office as governor. That has allowed him to wave off questions about his holdings since then. (Although Romney had previously derided the idea that a blind trust absolved Senator Ted Kennedy of responsibility, and Romney’s trust is considerably less “blind” than most.)

But from the mid 1990s through 2002, Bain Capital and Romney personally had enormous wealth, leverage, relationships, and influence that translated into an increasingly wide range of often difficult-to-unravel investments — some of which might look sketchy to average Americans.

And, in some cases, while he was running the Olympics, Romney made personal investment decisions in tandem with those made by Bain — making it hard to believe he was really out of the Bain loop.

One of those is DDi Corp., which Bain Capital took over in 1996, while Romney was still unambiguously in charge.

Bain took DDi public in 2000, and over the following year sold off two-thirds of its shares, at a reported $36 million profit. Romney personally signed the SEC documents reporting those sales — as well as the documents reporting his own sale, in the same time period, of some $4 million of his own personal DDi shares.

DDi’s stock collapsed soon after, falling from $28 a share to pennies. Among those hit was the Massachusetts pension fund, which had close to $350,000 invested in DDi.

The SEC claimed that Lehman Brothers’ research business over-touted the stock, under pressure from DDi, Bain Capital, and Lehman’s banking arm, which helped underwrite the DDi IPO. Lehman later paid a massive settlement to resolve that and a host of similar SEC charges.

The SEC did not accuse Bain Capital or Romney of wrongdoing in the DDi case, but it certainly smacks of the type of insider-always-wins stock manipulation that outraged people in the housing-market collapse.

Romney’s response, when the case made news while he was governor, was to say that he was on leave of absence for the Olympics at the time. Maintaining that excuse is even more vital for him as he runs for president, in the aftermath of banking scandals.

PROFITEERING, IN BERMUDA?

Then there is the case of Endurance Specialty, one of several casualty insurance companies that sprung up immediately after the 9/11 attacks, which some accused of profiteering off the tragedy.

Endurance Specialty was created in December 2001, and was one of the first major investments of Golden Gate Capital — a fund started by former Bain Capital managers, consisting primarily of large investments from Bain and from Romney personally.

As Endurance Specialty itself proclaimed in its 2002 prospectus, there was an “attractive opportunity” because “many global property and casualty insurers and reinsurers are currently experiencing significantly reduced capital” due to several factors, including “the World Trade Center tragedy.”

In other words, existing insurance companies had their money tied up waiting to sort out 9/11 claims — just as fear-driven customers were desperate to add more coverage, and willing to pay skyrocketing premiums. Companies like Endurance Specialty were able to charge 300 to 400 percent more than pre-9/11 rates, according to reports at the time.

That business can be viewed either as profiteering, or meeting a need.

Either way, Endurance Specialty did do one thing Romney is sensitive about: the company avoided paying US income taxes by basing its operations in Bermuda. It set up shop there, even though almost all of its funding and management were American, and two-thirds of its sales were in the US.

In its prospectus, the company even claims to have received assurances from the Bermuda Ministry of Finance that Endurance Specialty would be exempt from any newly passed taxes there until 2016.

Romney still has at least $2 million invested in Golden Gate, according to his financial disclosure of 2011 (and his wife Ann has at least $250,000), and Golden Gate has sold off its Endurance Specialty holdings — presumably meaning that Romney made money from his investment in the tax-sheltered company.

There was plenty of press back in late 2001 about Golden Gate’s involvement with Endurance Specialty — not just in investors’ trade publications but mainstream media including the Boston Globe. Certainly Romney could have withdrawn his own investment, if not Bain Capital’s — so it behooves him to argue that he was too busy in Salt Lake City to have paid attention to his investments.

There is one more reason that Romney may want to play down his investment persona during the Shadow Years: it may reveal that his much-touted Olympic turnaround was not quite the heroic effort he claims.

Saving the Salt Lake Olympic Games after the bribery scandal is a crucial piece of Romney’s biography — and he was well aware of the political value at the time. The Boston Globe reported that, when pleading for John Hancock to return as a major Olympic sponsor, Romney told his longtime friend and Hancock CEO David D’Alessandro that if the Olympics were not a success, “I won’t be anything anymore in public life.”

Running the Olympics involved many things, but the most important was selling sponsorships — a task that Romney describes at length in Turnaround, his 2004 book about the Olympics experience.

But Romney has never revealed what deals he made to get those $300 million worth of sponsorships (in cash, products, and services) — he exempted those agreements from his pledge of total transparency for the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC), and they have never been made public. That’s a mighty selective, and potentially self-serving, definition of transparency.

So we don’t know whether Romney used any of his leverage at Bain to help him get those career-saving sponsorships.

There are at least a couple of curious coincidences.

One is Gateway, which ended up as the provider of 4000 free computers.

As Romney describes in Turnaround, every computer maker had turned down the crucial sponsorship, including Gateway. “We were about 30 days out from our September 30, 1999, drop-dead date,” Romney wrote. “If we didn’t have a computer sponsor by then, we would have to start buying them at retail.”

Gateway came on board only after what Romney describes as a highly unusual mano a mano meeting with the company’s CEO.

What we do know is that in 2001, according to SEC documents, Gateway made a deal for services from Bain Consulting — payment for which came in the form of options to buy $5 million of Gateway common stock at a price above what it was trading for at the time.

Jon Huntsman Sr. (father of the presidential candidate) was another who had a change of heart, and later found doors open at Bain.

Huntsman repeatedly insisted that he would not contribute to the Olympics — even as late as the very week when, in a reversal, he wrote a million-dollar check. Huntsman’s support was crucial, many said at the time, to convince other Utah philanthropists to follow suit.

A year later, Bain Capital provided the bulk of a $600 million investment that allowed Huntsman’s company to complete a purchase of Imperial Chemical Industries, making Huntsman Corp. the world’s largest privately held chemical company at the time.

To some, that windfall of assistance from Romney’s company looked like a quid pro quo for Huntsman’s help raising the money for the Olympics to succeed. It raised enough questions that a SLOC spokesperson had to deny that Romney had anything to do with the deal.

DOING BUSINESS

The Gateway and Huntsman deals (first reported by the Phoenix in 2007) could have been purely coincidental. But it certainly wouldn’t be out of character for Romney to use that kind of leverage from one area of his influence to get results in another.

Bain Capital was a pioneer in that kind of synergy. Examples abound of one Bain-controlled company helping another. Staples became a huge buyer from American Pad & Paper; Mattress Discounter stores pushed Sealy mattresses; and Bain-funded start-ups received key early contracts with Bain-owned companies.

And the apparent conflicts of interest didn’t bother Romney, as he made sponsorship deals with Bain-held companies, like Sealy; companies he helped run, like Marriott; or companies where his son worked, like monster.com.

The most telling, though, is a deal that ultimately did not get made — with Staples, where Romney served on the board, and held 50,000 shares worth more than $1 million. A Bain Capital fund held 10 times that stake in the company in 2000 — and increased its holding to more than three million shares in 2001, according to SEC documents.

As Romney describes it in Turnaround, Staples CEO Tom Stemberg had no interest in the office-supplies sponsorship. But he agreed after Romney sweetened the deal to include “lobbying SLOC board members and other corporate contacts to switch their office-supply contracts to Staples.” That proposal was so valuable, Stemberg offered an additional $1 million after Romney learned that Office Depot had beaten Staples to the deal. (Office Depot insisted on keeping the sponsorship.)

It’s not hard to speculate that some of those “other corporate contacts” might have included Bain companies — and to wonder whether Romney was making similar offers, leveraging his Bain connections, to land other Olympic sponsors.

That kind of deal-making could help explain why Romney wanted to keep presenting himself as Bain Capital’s owner, president, and CEO, with some control over the company — and not as the fully separated retiree he describes now.

But it might also say something much more important.

If Olympic sponsors were paid off with business from Bain-controlled companies, then Romney’s Salt Lake success seems less a matter of skillful management, and more a function of his ability to buy what he wants. To most voters, that’s a far less presidential trait.

To read the Talking Politics blog, click here. David S. Bernstein can be reached at dbernstein@phx.com and you can f ollow him on Twitter @dbernstein.