Regency Era Prime Ministers-William Lamb

Regency History

Often in my research I keep needing to find who was leading the government and do this through every book. I thought that having the list handy would be good, and then turning it into a research webpage even better. Here is the list. After I post a few more Timeline years and write some more, I will work on the web page with notes about each PM.

The next PM I am doing is William Lamb, and I am hosting a page devoted to him and then all our period PMs at Regency Assembly Press. That page is here.

William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland

04/02/1783

12/19/1783

Whig

William Pitt the Younger

12/19/1783

03/14/1801

Tory

Henry Addington 1st Viscount Sidmouth, “The Doctor”

03/14/1801

05/10/1804

Tory

William Pitt the Younger

05/10/1804

01/23/1806

Tory

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

02/11/1806

03/31/1807

Whig

William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland

03/31/1807

10/04/1809

Tory*

Spencer Perceval

10/04/1809

05/11/1812

Tory

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

06/08/1812

04/09/1827

Tory

George Canning

04/10/1827

08/08/1827

Tory

Frederick John Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

08/31/1827

01/21/1828

Tory

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

01/22/1828

11/16/1830

Tory

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

11/22/1830

07/16/1834

Whig

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

07/16/1834

11/14/1834

Whig

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

11/14/1834

12/10/1834

Tory

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet

12/10/1834

04/18/1835

Conservative

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

04/18/1835

08/30/1841

Whig

Tory* (Tory government, PM a Whig)

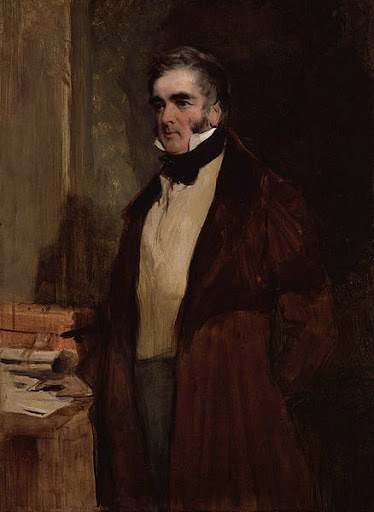

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne

Born 03/15/1779 London

Died 11/24/1848 Brocket, Herts

Major Acts:

Dissenters’ Marriage Bill 1836 – legalized civil marriage outside of the Church of England

Cuckolded by Byron

Viscount Melbourne had two lives – the first as the cuckolded husband in one of the most scandalous affairs of the nineteenth century, and the second as senior statesman and mentor to Queen Victoria.

Born William Lamb, in 1805 he succeeded his elder brother as heir to his father’s title. Now known as Lord Melbourne, he married Lady Caroline Ponsonby. It was a marriage which was to cause him no small amount of grief.

He first came to general notice for reasons he would rather have avoided, when his wife had a public affair with poet Lord Byron. The resulting scandal was the talk of Britain in 1812.

In 1806 he was elected to the Commons as the Whig MP for Leominster, where he served 1806-1812 and 1816-1829, before joining the House of Lords on his father’s death

He was Secretary for Ireland 1827-28, and Home Secretary 1830-34, during which time he cracked down severely on agricultural unrest.

On Grey’s resignation in 1834, King William IV appointed Melbourne as the Prime Minister who would be the ‘least bad choice’, and he remained in office for seven years, except for five months following November 1834 when Peel was in charge.

Without any strong political convictions, he held together a difficult and divided Cabinet, and sustained support in the House of Commons through an alliance of Whigs, Radicals and Irish MPs.

He was not a reformer, although the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835 did ensure that the growing middle class secured control of local government.

Efficient PM

But he was efficient in keeping order, raising taxes and conducting foreign policy.

Melbourne also had a close relationship to the monarch. He was Queen Victoria’s first prime minister, and she trusted him greatly. Their close relationship was founded in his responsibility for tutoring her in the world of politics and instructing her in her role, but ran much deeper than this suggests.

Victoria came to regard Melbourne as a mentor and personal friend and he was given a private apartment at Windsor Castle.

Later in his premiership, Melbourne’s support in Parliament declined, and in 1840 it grew difficult to hold the Cabinet together.

His unpopular and scandal-hit term ended in August 1841, when he resigned after a series of parliamentary defeats.

Lady Caroline Ponsonby- Lamb was not a typical politician’s wife.

The daughter of Frederick Ponsonby, 3rd Earl of Bessborough, and the granddaughter of the 1st Earl Spencer, she was born in 1785.

Lady Caroline married Lord Melbourne, in 1805. After two miscarriages, she gave birth to their only child, George Augustus Frederick, in 1807.

He was epileptic and mentally handicapped and had to be cared for almost constantly. Lady Caroline was devoted to him.

In 1812, Caroline read Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and declared:

“If he was as ugly as Aesop, I must know him.” On meeting Byron that summer, she famously noted in her diary that he was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”.

They began an affair which lasted until 1813, but even after it finished Lady Caroline’s obsession with the poet continued. She published a novel, Glenarvon , in 1816 containing obvious portraits of herself, her husband, Byron and many others.

Embarrassed and disgraced, Melbourne decided to part from his wife, though the formal separation did not occur until 1825.

Lady Caroline died in 1828, aged 42, her death hastened by drink and drugs.

Lord Melbourne, not yet prime minister, was by her bedside.

“It is impossible that anybody can feel the being out of Parliament more keenly for me than I feel it for myself. It is actually cutting my throat. It is depriving me of the great object of my life.”

First Ministry

07/16/1834 11/14/1834

OFFICE

NAME

TERM

First Lord of the Treasury

Leader of the House of Lords

The Viscount Melbourne

July–November 1834

Lord Chancellor

The Lord Brougham

July–November 1834

Lord President of the Council

The Marquess of Lansdowne

July–November 1834

Lord Privy Seal

Earl of Mulgrave

July–November 1834

Home Secretary

Viscount Duncannon

July–November 1834

Foreign Secretary

The Viscount Palmerston

July–November 1834

Secretary of State for War & the Colonies

Thomas Spring Rice

July–November 1834

First Lord of the Admiralty

The Lord Auckland

July–November 1834

Chancellor of the Exchequer

July–November 1834

Leader of the House of Commons

Viscount Althorp

July–November 1834

President of the Board of Trade

July–November 1834

Treasurer of the Navy

Charles Poulett Thomson

July–November 1834

President of the Board of Control

Charles Grant

July–November 1834

Master of the Mint

James Abercromby

July–November 1834

First Commissioner of Woods and Forests

Sir John Hobhouse, Bt

July–November 1834

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Lord Holland

July–November 1834

Paymaster of the Forces

Lord John Russell

July–November 1834

Secretary at War

Edward Ellice

July–November 1834

Second Ministry

April 1835 – August 1839

OFFICE

NAME

TERM

First Lord of the Treasury

The Viscount Melbourne

April 1835–August 1839

Lord Chancellor

In Commission

April 1835–January 1836

The Lord Cottenham

January 1836–August 1839

Lord President of the Council

The Marquess of Lansdowne

April 1835–August 1839

Lord Privy Seal

Viscount Duncannon

April 1835–August 1839

Home Secretary

The Lord John Russell

April 1835–August 1839

Foreign Secretary

The Viscount Palmerston

April 1835–August 1839

Secretary of State for War & the Colonies

The Lord Glenelg

April 1835–February 1839

The Marquess of Normanby

February–August 1839

First Lord of the Admiralty

The Lord Auckland

April–September 1835

The Earl of Minto

September 1835–August 1839

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Thomas Spring Rice

April 1835–August 1839

President of the Board of Trade

Charles Poulett Thomson

April 1835–August 1839

President of the Board of Control

Sir John Cam Hobhouse, Bt

April 1835–August 1839

Secretary at War

Viscount Howick

April 1835–August 1839

First Commissioner of Woods and Forests

Viscount Duncannon

April 1835–August 1839

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Lord Holland

April 1835–August 1839

Viscount Duncannon served concurrently as Lord Privy Seal and First Commissioner of Woods and Forests.

August 1839 – September 1841

OFFICE

NAME

TERM

First Lord of the Treasury

Leader of the House of Lords

The Viscount Melbourne

August 1839–September 1841

Lord Chancellor

The Lord Cottenham

August 1839–September 1841

Lord President of the Council

The Marquess of Lansdowne

August 1839–September 1841

Lord Privy Seal

Viscount Duncannon

August 1839–January 1840

The Lord Clarendon

January 1840–September 1841

Home Secretary

The Marquess of Normanby

August 1839–September 1841

Foreign Secretary

The Viscount Palmerston

August 1839–September 1841

Secretary of State for War & the Colonies

Leader of the House of Commons

The Lord John Russell

August 1839–September 1841

First Lord of the Admiralty

The Earl of Minto

August 1839–September 1841

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Sir Francis Thornhill Baring

August 1839–September 1841

President of the Board of Trade

Henry Labouchere

August 1839–September 1841

President of the Board of Control

Sir John Cam Hobhouse

August 1839–September 1841

First Commissioner of Woods and Forests

Viscount Duncannon

August 1839–September 1841

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The Lord Holland

August 1839–October 1840

The Lord Clarendon

October 1840–June 1841

Sir George Grey, Bt

June–September 1841

Secretary at War

Thomas Babington Macaulay

August 1839–September 1841

Chief Secretary for Ireland

Lord Morpeth

August 1839–September 1841

The Third Ministry was during the time of Victoria.

Family

Apparently Lamb had a dark side once all the brouhaha with his wife was done. He had married Caronline Ponsonby who stated she did not like Byron’s poetry and then spent her life in an open affair with Lord Byron. A man who had been a friend of Lamb’s when they were at University together.

They had a premature daughter and one son, George Augustus Frederick, born on 11 August 1807, who possibly had severe autism. Until Byron, they had a happy life. Caroline died in 1828, after Byron had died, and had also married Caroline’s cousin, who later separated from him.

Aside from the rumors that circulated about Byron at such time, later in life rumors circulated against the widower Lamb. Rumors suggesting that he may have engaged in spanking of high-born ladies, but whipping of those from the streets.

The Writing Life

My current writing project, a Fantasy, the third part of my trilogy on the son of Duke. It is the third in what I started when I left college. I finished the second part about 2 years ago, and so now I will wrap it up and reedit it all. It is tentatively titles, Crown in Jeopardy, the third book in the Born to Grace tale.

It opens with our hero setting up a trap for the enemies.

Chapter 2: Cynwal’s Folly (Continues)

Would Arthur Argent have coordinated attacks from Gwynedd, and from Andover without having Cynwal also part of the plot. No. Cynwal was part of Arthur’s conspiracy. It was not Hyfaidd who had instigated it all. Arthur Argent may have done so, but the Clanrex was part of the plot. Now he was going to pay. Caradoc administered high justice and he had decided on the sentence for Cynwal’s hand in the plot. One that had led to the death of King Richard.

Someone was going to see to it that Cynwal did not leave the field that day. That he was killed in battle. If Caradoc had wanted to ensure that the tale was spread around, he would have put a bounty on the man’s head. Caradoc knew that Cynwal had placed one of a thousand gold on his head. Enough money to keep any man in comfort forever.

Even the Earl of West Hills could live well on a thousand gold, though perhaps not as an Earl was supposed to. “Ah, there.” Cynwal and his closest troops were clear of the caltrops and holes on the battlefield and trying to regroup. They could sense the thousands that were spreading out from the camp. And that many were going after him. “Jamus, there! We attack there.”

Jamus looked back to Caradoc and nodded showing that he heard. He didn’t even shake his head which the man would have if he had no intention of taking Caradoc towards the source.

The men of Northmarch had an advantage knowing that they had turned this attack upon them into an ambush against the attackers. That hiding thousands in the camp had allowed them to spring forth with a host, perhaps not as a great as those that attacked, but nearly so. So many soldiers, and so many archers, that when the attackers were mired in the battlegrounds, they did not notice how many losses they were taking, while the defenders barely took one. The enemy had thought they would have charged and been against the Northmarchers quickly. Surely more than 1000 had fallen to the caltrops, or their horses turned lame in the attack, or the arrows piercing into them.

And very few of Northmarch had been wounded. Caradoc raised his sword and shouted “MacLaughlin!” The battle cry.

Again taken up by hundreds and then thousands. Arrows loosed over his head claimed another hundred or two hundred of the enemy. And Cynwal turned and saw Caradoc then. He had nowhere near the sic hundred horsemen who had charged some few minutes before. Much less, but enough that he had men that would fight and kill. That was the thing that surely gave the Clanrex confidence. He thought he had enough men to kill Caradoc. If his men were caught in a trap and suffering great losses, then he was determined to cause many deaths among the enemy as well. An enemy who had continually hurt the men of Powys.

“I would not want to be you, Cynwal, if you do not attack us.” Caradoc said to himself. The man would lose his hold over the clans, he was sure. And then if he did attack, was he as good a fighter as men said about him. Caradoc had fought duels to reduce the bloodshed. He had fought leaders before. He had killed Hyfaidd, the son of Cynwal. That should make the father wish to seek vengeance. Caradoc was right there. He waved his shield and sword at Cynwal who was looking at him.

What Caradoc wanted to force was Cynwal charging against him and the men he had with him. But Caradoc had no need to personally fight the Clanrex. Caradoc knew he was a decent fighter. And perhaps one of the best in his command. But there were other men as good, or better than he. They could fight Cynwal instead. Or, Iain could shoot at him from the wall. Caradoc had told the man who was considered one of the best archers in all of the clan, that it would not hurt his honor if the Clanrex approached within five feet of him and then Caradoc saw an arrow embedded in his head.

Iain chuckled. Well the men of Cynwal seemed to be rallying to him and beginning to form up. Forty, fifty of them. “I hope you are pleased,” Jamus shouted. “You got there attention and they are going to come this way. You do realize that there are more men then we have in this lane, and with those on foot, we shall be outnumbered here.”

Caradoc heard all of that. Jamus had a way of shouting that he could hear such things. Alain, who was now laughing as he held his shield to clout those who came to close said, “Well done.” The man would use a mace against any enemies that he truly had to hit, but the shield had the arms of Valens upon them, as did his surcoat over his armor. All knew his function. Caradoc was sure that some who stood against the Vater were glad to face a priest of the war god for he would try to disarm before trying to kill. If his opponents treated him the same, then those fighting Alain might survive the day with their lives.

Jamus was in the second rank of horsemen that were pushing against the enemy. Caradoc and Alain were in the third Rank. And behind came many more warriors. Caradoc felt it more than he saw it but the men in front of him from Northmarch were expanding their frontage. Then Jamus shouted back, “Hold Caradoc. Let us create a barrier!”

He knew that Jamus was serious. And he also had the Vater of Valens to help him. Jamus was sure to tell Clarisse, too, if Caradoc was too aggressive at that moment. He could shout his challenge, for the men still were doing so. Instead he hefted his sword and positioned his shield to be defensive. More of the men behind him would have to come forward and strengthen the line, and Cynwal was most likely going to arrive before that.

Looking to the far left, that was what was important. Cynwal was focused on hate. A chance that Caradoc had hoped to exploit. Avram led a large group of men along the lane that was farthest that way. Behind them, Frederick led another contingent. Those two, if they broke free, which had been the plan, might flank the enemy and cause such havoc that very few would be able to rout. If the day went against the men of Powys.

And since the enemy had only expected twelve hundred and found that they were fighting nearly five times that many warriors. He knew that they were already upset and disappointed.

A man broke through the lines in front of him and was doing his best to get at Caradoc. Not Cynwal, but large enough that he was probably one of Cynwal’s bodyguard. A man who probably had been instructed to kill Caradoc just as he had told so many to do their best to kill Cynwal.

Caradoc was at a standstill, and the enemy had a little momentum to his charge. Caradoc braced himself and raised his shield. He was in time to deflect the blow that was aimed at him. But then he had trained to be able to do that for countless hours. Years.

Combat though, was when his life was most at risk. This time as all the other times he had been involved in a fight. And the times that he was involved were increasing in frequency. He did not always leave a fight whole either. By directing battles and not participating in them as a fighter he had a better chance of not bleeding during the fight.

By not being the recipient of an enemies blows, he might not end up bruised. And maybe even his feet wouldn’t get so hot. That was more and more bothersome. That his feet were so damn hot. It made him angered.

A second blow was deflected by his shield. Vater Alain was not going to help get rid of the attacker, for he was trying to be a man defending, and not attacking. The men of Powys worshipped Valens too.

Caradoc saw no help for it, and stood quickly, pushing against the stirrups. Rising he deflected a third blow even as he brought his own sword twisting to slash under the man’s shield he faced. That let his sword slash upwards on the other side of the shield and he knew he hit the man’s shield arm, though the angle did not allow any cutting except perhaps against the strap.

Recovering his sword, he tried to pull hard against any constraint. His sword was very sharp, and if it found a think leather tie, it might cut it. With his sword free he quickly hit it against the man’s shield, and it did seem to move a little. The man once more tried to strike and Caradoc moved his shield in between them. He was there for every strike. And the man had another that he wanted to send Caradoc’s way. Not that Caradoc knew he was very fast, or absurdly fast but the man seemed slow. He was very tall, but he was slow.

And so Caradoc struck again trying to get over the shield but the big man had a big shield. Caradoc’s sword glanced off the top of the rim of the large shield. And the man’s shield shook again. More than it should have. Caradoc must have damaged the ties, he thought. Once more under, and there the enemy had a weakness.

Once more under and pull hard to cut the leather ties and any other armor he could reach. He also had to place his shield between the enemies blade and his head once more. The man should have learned to very his attack. It was too predictable.

Though the enemy losing his shield to the ground was sure to force a change in his routine. As the shield fell away, Caradoc did not want to give him much time. He slashed out again and struck against a now exposed shoulder. He struck hard and though he did not cut into the bone, the man had armor there, he did bruise that shoulder badly. The next strike Caradoc aimed for the helmet. Let him ring a bit.

A solid hit on the man and his head. Time for another. These could be very painful if they kept up. More to do with all that metal on your head being pushed about and how your neck held up. Caradoc would have to be lucky to have his sword cut through the helmet, which was pretty thick steel. But there were places of weakness in the head area. The eye slits, for instance.The neck was always thinly protected, even if there was chainmail there. It had to do with the articulation. If you wanted to see anywhere but straight ahead, you would want to move your helmet about, just as you could do with your head without a helmet. So the neck area was not solid steel.

It took good arm control to move the tip of the blade to where you wanted it to go. But then man squires, especially the sons of the great lords, learned how to do that long before they were considered for advancement to knighthood. Caradoc had mastered it years ago.

Fighting the man, though, also kept others of Powys from engaging him, and should one of those others happen to be Cynwal, then it would be too dramatic for him and the rest of the army. An army that should have had one person kill the Clanrex by then. A thousand gold pieces Cynwal would give to any who killed him. Maybe that was why the warrior still had not retreated. He had no shield and his head must have hurt terribly by then.

“Retreat man. Do you want me to kill you!” Caradoc shouted at the man. Striking once more on the man’s head.

Their steeds were well trained, for they allowed the two men to face each other without too much jostling about. “Never! Swine!”

“Do you not think I shall kill you?”

“Hyfaidd was my friend!” The fool said. That decided it for Caradoc. Hyfaidd was the worst of any type of lord.