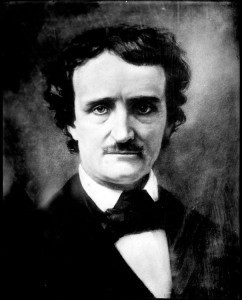

Edgar Allan Poe and the beginning of Crime Reporting (Stateside)

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

Over on Goodreads we’re having a discussion about Edgar Allan Poe’s Dupin Mysteries. Some really interesting discussion has been going on there, and the question of the history of Crime reporting and detective novels came up. Last October, during my Poe-athon, I bought, but did not read, “The Beautiful Cigar Girl” by Daniel Stashower. As I’ve already read the Dupin Mysteries, I decided it was time to read “The Beautiful Cigar Girl”. This is one riveting book, and I highly recommend it if you are a fan of Poe or even of murder mystery and reporting.

I find it interesting that the subtitle of the book is “Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder.” Also on my soon to be read list is Judith Flanders’ most recent book, “The Invention of Murder.” It’s an intriguing premise if you think about it. Murder was not invented in the Victorian era, but, rather, the reporting and sensationalising of it was. What does this have to do with Poe’s Dupin Mysteries? And how do they influence the detective novels that followed, such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes? The answers are in Stashower’s book, and for the sake of the current discussion going on at Goodreads, I’m making an attempt to roughly delineate them here.

In 1825 “The Kentucky Tragedy” went to trial. Known as the Beauchamp-Sharp murder case, it involved a young woman, Ann Cooke, who was seduced and cast aside by Colonel Solomon P. Sharp, solicitor general of Kentucky. She had his child and then turned to another suitor, Jeroboam O. Beauchamp, whom she agreed to marry if he would avenge her honor. Sharp would not agree to a duel and so Beauchamp, donning a disguise, stabbed him to death. Beuchamp received a death sentence and on the eve of his execution, Ann joined him in his cell where they both attempted suicide by poison and self inflicted stabbing. She died that night. He lived long enough to be hanged.

The story inspired many people to write about it, including Poe, who, finding it the stuff of Shakespearian drama, placed it in an Italian setting and began to serialise it. It was not received well, and when a close friend advised him he would do better staging his stories in France, Poe abandoned the story.

At the time, Poe was editing and writing for The Messenger. His best pieces were generally considered to be literary criticism. One of these he criticised, and quite soundly was a book called Norman Leslie by Theodore Faye. Faye had taken his story from sensationalised and highly pulicised Manhattan Well Murder in 1800, which was said to have been the first recorded murder trial in US history.

The Manhattan Well Murder involved the murder of a young woman named Gulielma Sands, who disappeared on the evening of 22 December 1799 after telling her cousin that she and her fiance, Levi Weeks, were to be secretly married. Two days later, some of her belongings were found near Manhattan Well in Lispernard Meadows, known as SoHo today. On 2 January, her body was recovered from the well. Weeks, who had been seen with Gulielma the night of her murder, and who, on the Sunday previous, had been seen taking measurements of the well, was the chief suspect. The trial was held on 31 March and 1 April, 1800, and after five minutes of deliberation, Weeks was acquitted.

Poe called Fay’s work “the most inestimable piece of balderdash with which the common sense of the good people of America was ever so openly or villainously insulted.”

The book, as was the trial so many years before, had proved quite popular with readers, and Poe’s criticism, which was usually respected, was met on this occasion with vehement disapproval on this occasion.

Though the Manhattan Well Murder was the first to be reported, the first efforts in crime and investigated reporting are generally attributed to James Gordon Bennett. Working as a reporter for the Enquirer, Bennet covered a sensational murder trial in Salem, Mass, of a retired sea captain, Joseph White, who had been murdered in his bed. (Incidentally, some say this story inspired Poe’s the Telltale Heart.) The state attorney general, however, issued a set of restrictions forbidding any further investigative reporting on the case. Of course Bennett, who felt (or at least declared) that he was performing a public service, was outraged.

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

Six years later, in 1836, when another sensational murder was in the public’s attention, Bennett, now the owner of his own very successful newspaper, seized upon the opportunity to advance the cause of journalism by “discovering and encouraging the popular taste for vicarious vice and crime.” Helen Jewett was a prostitute savagely murdered with an axe and then set fire to. Polite society was shocked by the very detailed reports which appeared in Bennett’s paper. No other paper felt the subject fit for print. Bennett felt otherwise. As he proclaimed when he was refused his right to report upon the murder in Salem, “It is an old, worm-eaten Gothic dogma of Courts to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press as destructive to the interest of law and justice. . . . The press is the living Jury of the nation.”

The man wanted to sell papers, in my opinion, and that was all. Neither did he limit his reporting to fact. Though he did visit the murder scenes, though he did dig into the histories of the victims and suspects, he often took an opposing course to those who, realising the profits the Herald was making, followed in his footsteps and covered the trial as well. When the murderer was discovered, and his conviction sure, Bennett took the opposing view (no doubt with a mind to sell a few more papers) and declared the suspect innocent. Enough of his readership sympathised with Bennett’s version of the murder’s story, that he walked free, though Bennett himself later admitted to believing in the man’s guilt.

In 1840 Poe was working for Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine, for which he wrote and published “The Man of the Crowd”, which took up, as “Politan” had, the workings of the criminal mind, and in which, using the art of deduction, the narrator reads the histories of passers by from observing the minutest details in their appearances.

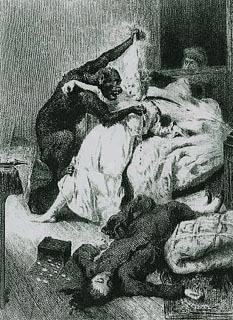

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

In 1841, Poe exercised his literary exercises in deductive reasoning once again in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”, and drew (for perhaps the first time) a great deal of positive notice. However, a handful of reviewers pointed out “there could be no great skill in presenting a solution to a mystery of the author’s own devising.” Poe understood that the effect of the story was accomplished by his having written it backwards. The idea of unraveling a web which he himself had woven troubled even him. He wanted to be the detective himself, and to apply these powers of deductive reasoning on a real case. The story by which he would find such an outlet was unraveling as he pondered upon this problem, and the fact that it was already the most sensational murder in U.S. history provided him with an already certain audience.

Mary Rogers was already a celebrity when her body was pulled from the Hudson River on 28 July 1841. Having worked for some time behind the counter at Anderson’s Tobacco Emporium, she was well known to much of the city as the beautiful cigar girl. Posters were made of her and she was very much admired.

If the case of Mary Rogers was fodder for Poe, it was also fodder for Bennett, who took up the case as his symbol for moral reform. But as he’d already set the pattern for investigative and sensational crime reporting, so did others, and the murder of Mary Rogers became an instant sensation.

As the murdered woman was from New York, and the body found in New Jersey, weeks went by before any real investigations occurred. In the mean time, theories were bandied about between the papers. Bennett began reporting about the incompetency of the men of law in both New York and New Jersey, and it was largely owing to him that the necessary money was raised to pay the investigators and to offer a reward for finding the murderer. Still the case stagnated, and when, a year later, the unsolved case seemed to have been very nearly forgotten, Poe put pen to paper, once more revived C. August Dupin, and attempted to solve the crime for himself, using his own genius and powers of deductive reasoning and relocating the story into that French setting he was so expert creating.

What was Poe’s conclusion? The present version of “The Mystery of Marie Roget” does not give it. Poe seems to have ramped himself up to some grand revelation and then omitted it. In truth, Poe’s conclusion was wrong. What is the true story of Mary Roger’s death? Well, I’m only half way through the “Beautiful Cigar Girl”, and the discussion of the story on Goodreads has not yet begun, and so, perhaps, I’ll save the details of her murder for next week.