The Housing Crisis and the Gulf Between the Rich and the Poor: Half of UK Workers Earn Less Than £14,000 A Year

Note: For US readers, £14,000 is approximately $22,000.

Note: For US readers, £14,000 is approximately $22,000.

In a new series, Breadline Britain, the Guardian is examining how the Tory-led government’s cuts are impacting on British families and individuals, and on the first day of the ongoing series, Amelia Hill provided an overview of the project, which has involved the Guardian commissioning a comprehensive study of the household finances of those in employment (or who are self-employed). As her introductory article explained:

Almost 7 million working-age adults are living in extreme financial stress, one small push from penury, despite being in employment and largely independent of state support … Unlike the “squeezed middle”, these 3.6m British households have little or no savings, nor equity in their homes, and struggle at the end of each month to feed themselves and their children adequately. They say they are unable to cope on their current incomes and have no assets to fall back on, leaving them vulnerable to something as simple as an unexpectedly large fuel bill.

Frank Field, the Labour MP for Birkenhead and former welfare minister, told the Guardian, “These figures are a mega-indictment on the mantra of both political parties, that work is the route out of poverty. What’s shocking about this is that these are people who want to work and are working but who, despite putting their faith in the politicians’ mantra, find themselves in another cul-de-sac. Recent welfare cuts and policy changes make it difficult to advise these people where they should turn to get out of it: it really is genuinely shocking.”

Bruno Rost, the head of Experian Public Sector, which conducted the research, and removed households in the “most deprived” categories from the findings, focusing instead solely on those who are working but “are nevertheless suffering high levels of financial stress,” said the group under scrutiny were “traditionally proud, self-reliant, working people”, who “are the new working class — except the work they do no longer pays.” He added, “These people say that being forced to claim benefits or move into a council property would be the worst kind of social ignominy and self-failure.”

Importantly, the Guardian‘s research has established that the Tories’ simplistic and deceptive claims — that there is either work (good) or benefits (bad) — is shockingly inaccurate. “Challenging the government’s claim that people are better off in work than on benefits,” Amelia Hill explained, “the exclusive research found that 2.2 million children live in families teetering on an economic cliff-edge — despite one or both adults earning a low to middle income. The households in trouble include couples without children who earn a gross annual income of between £12,000 and £29,000, or couples with two children on between £17,000 and £41,000.” She also explained that the research reveals that “having a job is no protection against homelessness and destitution in modern-day Britain.”

The findings echoed a recent report by Oxfam, noting that, as the Guardian put it, “more people in poverty were working than unemployed and the number in work but claiming housing benefit had more than doubled since 2005, to nearly 900,000″ — an alarming statistic in and of itself, but all the more alarming with the realisation that the Tory-led coalition government is savagely axing the benefits needed to keep poorer working families afloat. Oxfam added that people who were working but struggling to survive “were increasingly turning to charities for help,” and that thousands more were “accessing food banks this year than last.”

On Friday, the Guardian produced an interactive page in which, when you enter details of your income and family circumstances, you can find out where you stand financially in the UK as a whole — whether you are in poverty, on the edge of poverty, in the squeezed middle, comfortable, well-off, rich or super-rich.

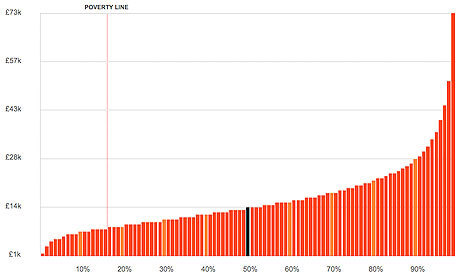

This is a fascinating project, but what impressed me the most was that it contained a graph (click to enlarge) showing how much people earn, which, significantly, demonstrates the problem with the much-quoted average income in the UK. As the Daily Telegraph noted in November, “The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that the average gross salary for full-time employees was £26,200 in 2011.”

This is a fascinating project, but what impressed me the most was that it contained a graph (click to enlarge) showing how much people earn, which, significantly, demonstrates the problem with the much-quoted average income in the UK. As the Daily Telegraph noted in November, “The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that the average gross salary for full-time employees was £26,200 in 2011.”

In contrast, the graph presented by the Guardian shows that the median income — after tax — is a much more startling £14,000 a year, meaning that half the working population earn less than this amount. It is also clear from the graph that over 15 percent of all workers are below the poverty line — earning less than 60% of the median income (around £8,400, which is roughly the amount a full-time worker on the minimum wage — £5.20 an hour — takes home).

I was interested in how this situation corresponded with the housing situation in the UK, where, as the Guardian reported last Tuesday, figures from the Office for National Statistics showed that the average UK house price was £229,000, but with significant regional variation. In London for example, the average house price is £388,000.

A couple on the median income — on £28,000 a year — are therefore excluded from entering the housing market as at no other time in living memory (or, as Shelter put it in a disturbing analysis of the housing crisis), “The UK is now more polarised by housing wealth than at any time since the Victorian era”), as can easily be appreciated from the traditional multiplier (3.5 times income) that was traditionally used to calculate the affordability of a mortgage (and is still a sensible indicator). Even with tax included in the median household income, taking it to around £34,000 a year, that makes an affordable house one that costs £120,000 — almost half the average cost of a house in the UK, and less than a third of the average cost of a house in London.

People don’t need to own their own houses, of course, but unaffordability also stalks the rental market. As I explained in an article last month, Rents Out of Control: How Londoners Are Being Fleeced by Greedy Landlords:

[I]n March, Shelter [the charity for housing and homelessness] reported that “renting a two-bedroom home in London is unaffordable for families earning less than £52,000 a year,” and, that “in eight London boroughs, including Hackney and Tower Hamlets, families would need to earn more than £60,000 a year.”

Shelter also established that “almost one in four London families now rents from a private landlord — an increase of 70 per cent in the past two years,” and discovered that “the rate of inflation on private rents in London was seven per cent in 2011, almost double the rate of inflation on the average London wage,” meaning that, with the typical London household income at less than £35,000 a year, “growing numbers of families are at crisis point, paying up to half of their income in rent each month as they struggle to continue living and working in the capital.”

Shelter’s report is here, and what is particularly clear from any study of the private rented sector is how completely unregulated it remains, after controls were removed under Margaret Thatcher, and how unscrupulous landlords are now pushing up rents to levels that are even higher than mortgages — especially in London and the south east.

Also under attack from the government is social housing — cynically and inappropriately described as subsidised housing — which has never recovered from Margaret Thatcher’s right-to-buy program, and the ban on councils building new social housing with the proceeds. The sector, which deals with around 3.6 million properties (with 1.4 million run by housing associations, according to 2005 data) has seen under-investment in new builds for many years, and is now suffering from government demands, in the Affordable Rent Programme, that rents for new tenancies be set at 80 percent of the cost of market rents — which will add to the strain on poorer workers, and, perversely, to the housing benefit bill.

In another ludicrous policy, more housing chaos will become apparent next April, when, as the Guardian described it, “tens of thousands of people living in social housing will have to find more money to pay for their accommodation or leave their homes.” Under the government’s ill-thought out and inflexible plans (although this is a description that is true of almost all their policies), social tenants “will have their housing benefit cut by £40 a month if they have a spare room and by £70 if they have two spare rooms,” or they can opt to be rehoused. At first glance, it perhaps sounds reasonable to try and address under-occupation in social housing, but many housing associations have, apparently in vain, warned the government that they have “a dearth of suitable homes” to rehouse tenants who “have received letters informing them that they may have to switch to smaller properties” — nearly 100,000 in total.

To cite just two examples, Iain Sim, the chief executive of Coast & Country, based in the north east, said his company “had 2,500 ‘under-occupiers’ but only 16 spare one-bedroom homes on its books,” and Monica Burns, north-east manager for the National Housing Federation, which represents England’s housing associations, called the new rules “futile and unfair.” She said, “Housing associations in the north-east have always been encouraged by government to build bigger homes so families could live in the same homes for life.” She also “warned the welfare bill could rise as social housing tenants migrated to the private sector,” explaining, “The government will then have to pay a higher rate of housing benefit to cover their rents for smaller homes,” and adding, “These are the consequences of a blanket policy that failed to listen to local people.”

Personally, I find it cruel that people with children will no longer have security of tenure under these plans, and will be required to move, for example, the moment a child leaves home. The Guardian also noted that, under the new rules, “children of the same sex will be required to share a room up to age 16, while those of different sex will have to share up to age 10.” This might sound reasonable, but in fact overcrowding is already at epidemic levels in social housing (although it is never mentioned in the mainstream media), and it strikes me as inconceivable that the rules can or will actually be enforced.

The ongoing effects of an overpriced, but artificially sustained housing sector in London and the south east — and the residue of Labour’s housing bubble elsewhere in the country — are causing widespread misery. As the Guardian also explained last month, data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) showed that, in 2011, almost 3 million people aged 20-34 were living with their parents, an increase of 20% (or around 600,000 people) on the figures for 1997, when Tony Blair’s government presided over the start of what would become an unprecedented housing bubble, one that has not been allowed to burst, and that is still hideously over-inflated in any areas of substantial employment.

The Guardian explained that, although the ONS stated that there were “a number of reasons why 1.8 million young men and 1.1 million young women were now living with their parents,” including “higher university costs, increasing rents and a credit squeeze,” it was “noteworthy that the increase over the past decade coincides with an increase in the average price paid by first-time homebuyers of 40% between 2002 and 2011.”

Earlier this month, the Observer also reported the dismal news that millions of young families “are entering an era of insecurity in which renting becomes the norm,” according to a Cambridge University study, commissioned by the independent Resolution Foundation and Shelter, which “warns of steep increases in the number of parents unable to buy their own homes,” and states that, “if the British economy remains stagnant, just over one in four people — 27% — will be in ‘mortgaged home ownership’ by 2025, compared with 43% in 1993-94 and 35% now.”

“Most alarmingly,” the article noted, “it is no longer just young, single people who are locked out of the property market and forced into an under-regulated rental sector due to rising house prices, falling real wages and banks that are unwilling to lend,” and explained, “The same difficulties are now besetting families with children, many of whom are paying half or more of their income in rent and, as a result, have little or nothing left at the end of the month to save for a deposit.”

The Observer added that, in the last five years, “the number of families with children having to rent private accommodation has soared by 86% — more than double the increase across all households (41%).”

The report also predicted that, without some sort of major economic upturn (something that is difficult to envisage in the West as a whole, but impossible to imagine under this wretched government) the shift from ownership to renting “will continue apace for more than a decade,” and “[t]he increase in the proportion of families with children who are renting privately will be most stark in London … rising from 25% now to 33% by 2025. Overall, it predicts that more than a third (36%) of British households will be renting by 2025.”

Realistically, there is only one answer to this growing epidemic of squeezed families and individuals, and increasing poverty, misery and homelessness, and that is to initiate a massive home-building programme — of genuinely affordable, not-for-profit social housing — with government support, creating much-needed economic demand in the economy, and much-needed jobs for the legions of the unemployed, and especially the young unemployed (over a million aged between 16 and 24).

To do that, of course, we need to depose the idiots and scoundrels currently clinging to power through their discredited coalition government, and — it would appear — either re-programme Labour politicians, or set up a whole new political movement.

This is a pretty serious demand — but just look at the alternative: doing nothing and watching the country sink into an economic death spiral, as the tax-evading criminal class — of politicians, bankers, businessmen and women, and unscrupulous celebrities — hide their loot in global tax havens, and the rest of us die a slow death.

Note: For another good analysis, see Polly Toynbee’s most recent Guardian article here.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to my RSS feed (and I can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, Digg and YouTube). Also see my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, updated in April 2012, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” a 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, and details about the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (co-directed by Polly Nash and Andy Worthington, and available on DVD here — or here for the US). Also see my definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all my articles, and please also consider joining the new “Close Guantánamo campaign,” and, if you appreciate my work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to my RSS feed (and I can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, Digg and YouTube). Also see my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, updated in April 2012, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” a 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, and details about the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (co-directed by Polly Nash and Andy Worthington, and available on DVD here — or here for the US). Also see my definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all my articles, and please also consider joining the new “Close Guantánamo campaign,” and, if you appreciate my work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers