The Real and the Unreal: A Manifesto

When I was in college, the task of the researcher was to find information. When I was in graduate school, it was to sort through information. This spring, when my students arrive at the university, I will tell them their task is to resist misinformation.

In the last twenty years, our relationship with information has changed radically — and that means our relationship to reality has as well. We are on the cusp of an age of unreality, and the danger it poses to us, and to the planet we inhabit, is enormous.

I’m sure that I sound alarmist, but let me explain what I mean. And let’s start with what I saw when I first entered Alderman Library at the University of Virginia as a college freshman: a long row of cases filled with drawers containing the library’s card catalog. My family was on the cutting edge of the technological revolution. As soon as we could afford one, we had purchased an Apple IIe, and I had typed my college application essays on it. But some of the freshmen on my hall were still using electric typewriters. By the time I graduated, we could all use the campus computer lab and print out our papers on dot-matrix printers, waiting our turn in the print queue. The card catalog had already been replaced by an online catalog, accessible from terminals in the library.

In graduate school, I learned to search for material not only in the library stacks and among the rows and rows of bound academic journals, or the back issues preserved in the basement on microfische, but also online, on databases like JStor. When I started teaching, I taught my students the arcane process of using the library’s online catalog, until one summer it was redesigned and I returned to find that it now looked and functioned like Google.

While I had been working on my PhD, the challenge had been finding information — locating my initial sources and following the trail of citations back to other relevant sources, eventually gathering a core group of texts. For my students, who arrived already starting every research project in the Google search bar, and many of whom did not even know how to click over to the more reliable Google Scholar, the challenge was sorting through the barrage of information — the 10,000 sources Google would spit out in response to a research question. Even the university library website, which now included what had previously been individually searchable databases, could return over 1000 sources to sort through. My students and I adapted. Like Aschenputtel, we learned to pick the lentils out of the ashes, the useful sources from the irrelevant ones.

This year, my students are arriving to a research landscape that is once again starting to radically alter. Last year, I started seeing the traces of AI writing in their papers — rhetorically perfect sentences in which they did or observed a, b, and also c, or experienced x, however y. In paper after paper they “queried,” as though ChatGPT had chosen its favorite word of the week. Unlike teachers who had forbidden the use of AI, I did not receive papers that were entirely AI-generated. I think because I had spelled out when and under what circumstances they could use AI, as well as the problems it poses (among other things, we watched Ex Machina), my students used it in smarter and more subtle ways. Despite the traces of AI vocabulary and rhetoric, I could still see their individual intellects and hear their distinct voices in their papers.

But this year, I’m a little scared. Not that they will use it in their writing — I have policies for that. But that they will use it in their research and turn in papers containing information fabricated by AI, citing sources that don’t exist. As I write this, the internet is being flooded with information and images that are not real or true. When I search for information on Google, the AI summary that my eye immediately and automatically rests on gives me facts that are not facts. For example, when I asked Google, “How many grammatical genders does German have?”, it initially told me that it has none. Someone, somewhere, must have caught that, because it now correctly answers that German has three.

My students have already been told, by busy high school teachers, to put their sources into online bibliography generators, which will produce the correct citations. But at least 50% of the time those citations are not, in fact, correct. Their high school teachers did not have the time to check all their sources for accuracy — or, indeed, existence. It takes half the semester for the students to realize that when I say I do, I really mean it. I check. I check everything.

We are about to enter a great age of misinformation. It will affect not only my classes but our society as a whole. Students have been told not to trust Wikipedia. What are they supposed to do with Grokipedia? What are we all supposed to do with Sora — especially once the identifying mark has been removed, as it inevitably will be?

In “On Fairy-Stories,” J.R.R. Tolkien wrote that writers of fairy tales are blamed for writing things that are not true — frogs turning into princes, for example. But, he argued, the existence of those tales is premised on a deep understanding of reality. If we did not know the difference between frogs and princes, the tale would be meaningless. Reading fantasy literature, he argued, requires knowing what is real and what is not. But he also contrasted real reality with what we often assume is reality — the human civilization we have created around us. A tree, a horse, a sword, are all real, he might have said. The office building in which you work from nine to five is half real (concrete) and half imagined (the idea that it’s an office building, rather than a cathedral). In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari writes that the basis of any human civilization is an imagined reality — the reality we have created by imagining it into being and agreeing that it’s real. That imagined reality includes money, governments, nations, laws, borders — even, as I tell my students, our university.

Starting now, we are going to have to get a whole lot better at differentiating between what is real (the moon), what is part of our imagined reality (NASA), and what is sheer unreality (the idea that the moon landing was faked). Teachers will have a role to play in that effort, but so will writers of fantasy. We should, by working on the boundary between the real and the unreal, between frogs and princes, be deeply attuned to the difference between them. Our creative work is threatened by the erasure of that boundary — if readers don’t understand the difference between the real and the unreal, our genre disappears. And our genre is precious, not just as a source of entertainment (although fantasy has served that crucial human function for generations, in the form of fairy tales, legends, and myths), but also because it has an even more important function.

Realistic literary forms represent the world as it is — they allow us to understand the society we are living in. They take the human imagined reality (social codes, the stock market) as a given. Jane Austen explores, in exquisite detail, the norms and conventions of her time. Fantastic literary forms represent the world as it isn’t. By presenting alternatives to it, they allow us to imagine other possibilities, other ways of being. They imply that our imagined reality is, in fact, imagined — a human construct that could be constructed in other ways. In doing so, they return us to reality — the underlying real reality on which our lives are fundamentally based. To the reality of the planet we stand on, the environment we live in and that we share with other very real animal species, and the fact of our own eventual deaths. They remind us that while princes only exist in imagined reality, frogs are deeply and fundamentally real, as well as threatened by pollution and climate change.

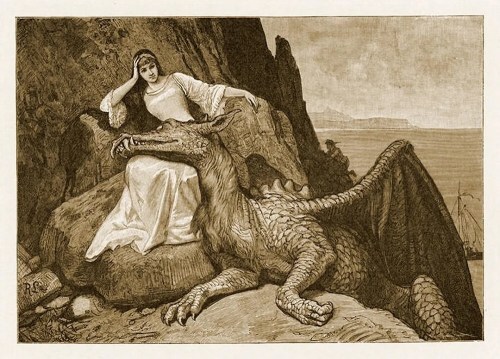

So we have a duty, I think — we writers of the fantastic. We need to forcefully make the point that fantasy is different from unreality, just as a fairy tale is different from a Sora video. Fantasy is a deep, rich tradition that has an important human function, which is to make us question what is real and help us understand that anything the human imagination creates (religions, governments, maps) can change. It helps us escape from the world of illusions created by tech overlords, who start to look like frogs croaking that they are digital princes.

In a world that is careening into unreality, let us continue to write about dragons, in the knowledge that we are doing the deeply important work of showing the richness of the human imagination, as well as the very real natural world that nurtures it and without which it would be impoverished. And let us resist the machinification, the AI-ification, of our field, our creative work, our own voices.

(The image is an engraving by Anton Robert Leinweber.)

newest »

newest »

I applaud your perception, and mission. However, i would like to point out that the problem may not rest in differentiating between the real and unreal (although that is necessary also), but in finding a way to enforce those social codes (such as those against falsehood)

I applaud your perception, and mission. However, i would like to point out that the problem may not rest in differentiating between the real and unreal (although that is necessary also), but in finding a way to enforce those social codes (such as those against falsehood)