A Plot with a Few Holes

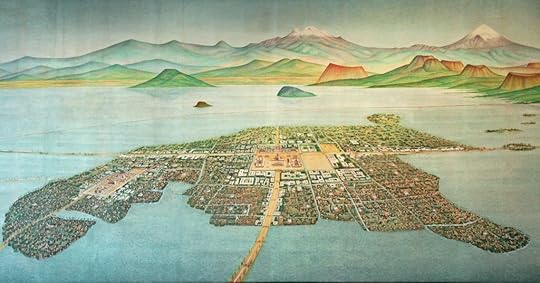

The cracks in Prince Nanzeta’s tale begin to show in July. Perhaps he forgot his story (unlikely) or, possibly, someone in one of his audiences somewhere pointed out to him the fact that the Sacred City of the Aztecs, Tenochtitlan, was actually located in the center of a lake with water all around. The landscape he had described replete with craggy cliffs and bottomless crevasses sounded, in actuality, much more like the royal seat of the Incas, Cuzco, many miles south in Peru.

In August, the “prince” arrives in Butte, Montana, maintaining his Aztec story and, for some reason, linking it to the Incas as if the two tribes were interconnected, somehow, friendly neighbors, though 2,800 miles apart in distance.

At this point, too, he takes on a much more arrogant air than he did in Denver. Where in Colorado, his reasons for condescending to commune with commoners was a necessary ruse that explained his eagerness to sit and spin his yarns for the pleasure of his fellow hotel guests, here, in Texas, followed by Montana, and then in Oklahoma, his attitude begins to feel decidedly more arrogant.

“I come from an aristocracy older than America and its people, and I have no place in my regard for time in my calendar to associate with the baser elements of American Society.”

Where before he admired the common man because he was not false and base and pretending at a nobility they were not naturally heir to, here he’s actually looking down on them as less than him, and making them feel it, too.

Here, too, the story takes on a few additional chapters, including the prophecies of “Red Blanket”, a Yaqui medicine man who had foretold of Nanzeta’s birth in the Aztec temple and how that young man would come to be a great leader of the Yaqui. He also includes a story of how a tribe of Pueblo tried to poison him by throwing snakes on him while they performed one of their snake dances.

Sometimes a tale is too tall to be believed, and the early Nanzeta seems to have understood this. Perhaps his success got to his head, or possibly he was becoming bored of his own story. It’s possible, too, that he simply enjoyed the thrill of convincing people to believe in something that was so obviously a lie.

In Dillon, Montana, our medicine man makes a slight alteration to his name and signs his name in the guestbook as “Manzetta” in with an “M” rather than the usual “N”, though this could simply be journalistic error or even difficulty reading the “prince’s” signature. Beneath his name someone wrote “Reggiano Parmesiano, Duke of Parrlle, Italy”. No doubt this is simply a joke, but it does leave one to wonder if they saw the name and thought to mock it by adding the next entry or, rather, if they saw him and thus were providing subsequent guests to understand that the young man was more likely Italian than Aztec. It’s possibly a clue to his origins. More likely it is one of several dozen red herrings provided by various means as this man’s story unfolds.

It’s here, too, in Dillon, that Nanzeta provides an explanation as to why he might be so bold (or ignorant) as to confuse his Inca heritage with his Aztec one. He is on record as saying that his mother was Inca and that she was of Peruvian royalty, whereas it was his father who was the descendant of Montezuma. A convenient (and necessary lie) but hardly a believable one.

When asked how he spoke English so well, he said he attended Stanford, but upon adding that he has made a tour of the world, he was asked at what age he managed to complete not one course but two at college. His answer is that he began Stanford at the age of fourteen.

At times, the narrative diverges for reasons apparently beyond boredom. It’s as if the challenge of remembering all the details of a fabricated story becomes too much. If one takes the early accounts of him, those which illustrate a very young man, hardly an adult, bearing an outlandish and yet streamlined narrative, challenged, yes, but patiently and graciously defended and compare those with the accounts that come in six months later with their alterations in spelling, the bizarre side stories and interjections of a contemporary but geographically distant and quite separate history and a much more hostile personality it seems possible, perhaps probable, that there are two actors rather than one. Only the descriptions remain identical. Or at least nearly enough so to suppose it is the same person, and it isn’t as if his description is of the ordinary kind, either.

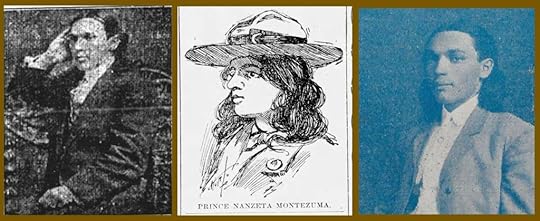

In April and May in Denver, he was described as “A dapper, long-haired, dark skinned Mexican youth, and “a swarthy young man, with very long and black hair”. A line drawing is included, as well, which is useful but not entirely decisive as to his identity (what do you think).

As to his age, it varies somewhat. For instance, in Denver he is 23 and then, later in that same month of May, he is 22. In Spokane, he was “said to be some 30 years but his looks belie that statement and 15 would come nearer what he appears”. In Butte, in August, he “looks not over 25 years of age.” In Oklahoma, in December he is described as “a small, dapper appearing young man of about 20.” It seems to me that these discrepancies are the difference between what he told people and what he appeared, and the line between the two is sometimes vague, but his struggle to be taken seriously on account of his apparent youth in contrast with the expertise he claimed was a sore spot for much of his early career.

In several reports of his appearance, scars are described, particularly when they were used as evidence of his adventures. In Butte he is said to have suffered a “bad cut on the back of his wrist” with a scar to prove it. In Salt Lake, he displayed a scar on his temple, where a bullet grazed it. In October, in Galena, Kansas in October, he showed off two scars on his right arm as proof of a saber wound during his duel with the Mexican soldier.

Another clue is offered in the descriptions of his speech, though it’s uncertain how reliable these are. In Butte in August he spoke with a “charming voice and beautiful English, bearing only the slightest accent” and “as an educated gentleman of refinement, fluent in speech and apparently well informed on all of the things he talks about.” In Dillon he was said to have spoken “with a foreign accent, but occasionally lapses into his native American tongue”. In Payson, Utah in September, his voice was described as soft and mellow with “a rich accent”. In November, while in Texas, his pronunciation was decidedly Spanish. December, in Oklahoma city, he told his story “in perfect English.”

Two marked exceptions occur in, however, in these descriptions of him in this first year of his “advent”. In one account while staying in Galena, he was said to have blue eyes, though the other newspaper accounts of him contemporary to this time identify him quite plainly as a Mexican, which would have made blue quite extraordinary, and may have simply been an error in transcription from written notes to typeset. The second detail which varies pointedly from the other accounts occurred in November in Hempstead, Texas. Here it was said as he was chased out of town that “his wig came off as he ran away”, but as the article, and those written around this time, were highly satirical in regard to the “prince”, I suspect this is a theatrical invention for the sake of sensationalism. However tongue-in-cheek this episode of the “Prince’s” career was reported, it’s worth describing in detail, for its here the “prince” appears to come into some real difficulty. The story begins much like it did in Denver, where he arrives at the hotel and makes an impression.

Arriving there on a recent night, the prince registered at the principal hotel, and by his appearance attracted a lot of attention. His foreign air, combined with his flowing hair and Spanish pronunciation, produced a powerful effect on the minds of the Hempstead people—they thought he was a real bona fide prince and were prepared to pay him the homage due to one of his exalted station.

He tells his stories and impresses his audience to the degree that they once again are moved to pay for his meal and to ply him with drinks and everything that can be offered him.

In the morning, however, the guests of the night before were greeted by the sunrise and “the rude shattering of the dreams which accompanied their sweet slumber” upon finding him on his box selling his remedies. “In his hand he held a quart bottle which he was loudly proclaiming as the only genuine cure for all the ills to which humanity is heir.” (A common claim.) He went on and on making wilder and wilder claims, and introducing one bottle after another, each containing an elixir more powerful than the one before it. The first cost the audience $1 each, the next was $5, but with a coupon was half of that if they returned the first bottle. Soon he sold out and pocketed what a group of skeptical onlookers assessed to be about $100 (a “century” in street-hawking terms and a good day’s work) and, “with a sweeping bow” stepped off his box and closed up shop. As he was putting away his wares, the group of skeptics, insences on behalf of the fools who had fallen for his act, they charged after him, chasing him with out of town with empty cans and firecrackers and a dog.

Down the road went Prince Montezuma, followed by the said hound and half the populace of the town. In the hurry of his flight, his wig came off and this was greeted by a fresh outburst from the pursuers. He made two jumps to the dog’s one and finally won out in the race by landing in an unused Pullman car from which he could not be dislodged. Prince Nanzeta di Velasco Montezuma, Prince of Incas, left Hempstead on the night train a sadder but a wiser man.

By the time he arrives in Oklahoma City in December, news of his preposterous story and the discovery that he is a “fakir prince” and a peddler of snake oil and corn cures has preceded him.

As if to lean into the part, he goes possibly a step too far. The name he writes on the register of the Lee Hotel is “Nantazeta Castro, Count of Gatamo, Venezuela. When asked to account for his credentials, he seems to lose the plot and claims that his name is the cousin of the Venezuelan president Cipriano Castro and, furthermore his people were the “Swiss of Venezuela”. Here, in his retelling of his history, the woman he has fallen in love with is not Mexican but a New Yorker whom he met while she was visiting Venezuela.

What is this sudden need to lay claim to a white identity? And yet, despite no mention of his dark skin, the description is the same.

Last evening a small, dapper appearing young man of about twenty years, with a girlish face and long wavy hair reaching to his shoulders, neatly but not extravagantly attired and carrying a cane, walked into the Hotel Lee…

The Daily Oklahoman, in reporting on the “prince’s” visit, took on an air of apparent suspicion and at times mockery.

He scarcely finished the signature when a commercial traveler stepped up to the princeling and with a smile of recognition, explained: Hello! You there! The last time I saw you, old man, you were selling resurrection plants over at Webb City, Mo.

Even though he had come to Oklahoma City to do something very similar, and had seemingly few qualms about letting his Denver friends know, he took a decidedly defensive tone, denied the whole and proceeded to explain, in perfect English, that he had never been to Webb City, and when a reporter presented his card to the “count’s” door some time later, he was more than prepared to make the story bigger and more elaborate than ever before, intermingling with wild abandon the ancient histories of Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, the descendants of Inca, and the tribe of the “Loqui” (there is no such thing, though, again, this could be journalistic error) as if they were all guests in a politically fraught ballroom rather than civilizations occupying three different continents.

The last straw in the article of that day was the last line which read, simply, “The police kept close watch on his movements all night.”

This left the “count” apparently incensed. He sent a line to the editor demanding an apology. And they did, though with a good bit of irony and sarcasm.

The count asserted that he considered the write up which he received in yesterday morning’s Oklahoman an insult, and cited as cause for grief the last two lines …

We apologize for this, and think perhaps the police should not have done it.

The count last night admitted he had sold medicine at Ardmore, and we apologize for that.

He said last night that it is the custom of his country for the people to wear long hair as it is a part of their religion and he felt that he had a right to wear long hair if he so desired.

Now, we deny having uttered or indited anything insinuative or disrespectful of the count’s tresses. We didn’t do it, …

(They hadn’t.)

… for we have long since avowed with Pope that

“Women man’s imperial race ensnare

And beauty draws us with a single hair.”

We also lament our own ignorance in supposing there were no counts in Venezuela or among its aborigines, but can readily realize now that the South American Indians probably took their cue from the play entitled “The Count of Montezuma,” a rank fake on Dumas’ “Count of Monte Cristo.”

The count’s casual admission that his title was an empty one caused us to surmise the existence of other vacuums but we apologize for that also.

The count also alleges that he is an actor, and as we are willing to concede that fact there is no room for apologies on that score, at least not from us.

It’s in December, however, in Oklahoma City, where the first major deviation in the “prince’s” story takes place. Up to this point, there have been additions to the story. It has certainly grown and become taller and more “epic:” in nature, but a crossroad seems to appear in Kansas that begins, if not to change the trajectory of the story, at the very least to confuse it. It’s here things begin to get strange and the quest for the truth of Nanzetta’s identity and origins seems impossible to pick out of the detritus of lies and deception.

It happens while he, as on previous nights, is sitting in a hotel as a crowd of eager listeners surrounds him. It is here he claims he spent many months on an expedition led by the great English explorer Harry Landes to Thibet and there “penetrated into the wilds of that country further than whites had ever ventured before.” It’s a mere mention in The Daily Oklahoman, but it’s one that will take on a life of its own, given time.

But first … a little about the phenomenon that was The Great American Medicine Show.