Exploring James A. Garfield: The Beginning of a Tragic Tale

Friends

The recent Netflix drama, Death by Lightning (2025), has thrust President James A. Garfield—a long-overlooked figure I’ve always admired—into contemporary consciousness. His remarkable story deserves attention: a dark horse candidate who rose to the presidency only to meet a tragic end. Beyond the assassination itself lies a fascinating historical tapestry involving primitive medical practices, Alexander Graham Bell’s desperate attempt to save a dying man with his newly invented metal detector, and a fateful journey to the New Jersey shore that altered American history.

From the humble classroom to the battlefield, from a farmer to the Ohio Senate Chamber, James Garfield’s path to the White House is a story for the ages…

Back StoryOn a cold November day in 1831, James Abram Garfield entered the world in a modest farmhouse in Moreland Hills, Ohio. The son of Abram Garfield, a hardworking farmer who once shouldered a musket in the War of 1812, James would never know his father. At two years old, the Garfield family lost Abram, leaving his mother, Eliza Ballou Garfield, to shoulder the burden of raising her children in the harsh reality of nineteenth-century rural poverty.

From his early days, James was instilled with a hard-work-pays-off ethic, rising before dawn to milk cows and mend fences for his mom. Between harvests, he earned money at a local tavern, his small frame straining under barrels that men twice his age struggled to lift. Despite limited resources, Garfield had a thirst for knowledge. He was a voracious reader, and the woods became his classroom until, at sixteen, he attended a local school where he excelled in subjects like math and Latin. His teachers recognized his potential and encouraged him to pursue further education.

After graduating with honors from Western Reserve Eclectic Institute in 1856 (now known as Hiram College), Garfield returned to its halls, this time standing at the lectern rather than sitting before it. His academic versatility soon propelled him to the presidency of the institute in 1856, a position he would hold until 1861. The breadth of his teaching reflected both his intellectual range and the institute’s modest faculty size, as he was the primary teacher of the classics, languages, and geometry.

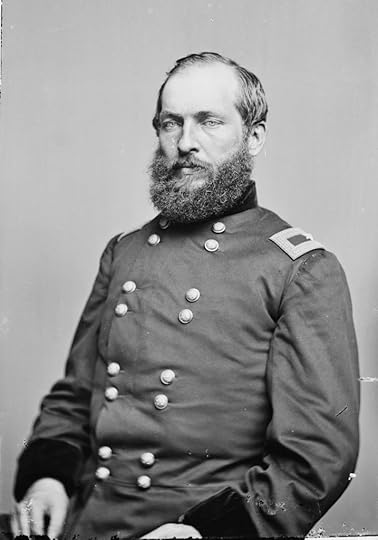

By Mathew Benjamin Brady – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. Civil War

By Mathew Benjamin Brady – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. Civil WarGarfield’s fervent opposition to slavery led him to insist that western territories must remain free soil. While he stopped short of endorsing John Brown’s violent actions at Harper’s Ferry, he viewed Brown’s subsequent trial and execution as a potential catalyst for change, writing that it might herald ‘the dawn of a better day.’

As the Southern states began seceding from the Union, Garfield strongly opposed their departure and advocated military intervention. ‘The sin of slavery,’ he declared, ‘requires blood sacrifice for its forgiveness.’ When Fort Sumter fell to Confederate forces in Charleston Harbor, Garfield saw opportunity in catastrophe-a galvanizing moment that would rally Northern public opinion behind armed conflict with the rebellious states.

As the Civil War erupted, Garfield assembled the 42nd Ohio Infantry Regiment in the sweltering days of August 1861, climbing from Lieutenant Colonel to Colonel before the summer’s end. His military reputation rested on two remarkable feats: first at Middle Creek in January 1862, where his small force routed the larger Confederate army and secured eastern Kentucky for the Union; then at Chickamauga in September 1863, where he galloped through enemy gunfire to deliver crucial intelligence. These actions helped propel him to Major General-the youngest officer to hold this rank.

1880 Republican National Convention The interior of the “Glass Palace” on June 2, 1880, during the Republican convention. Library of Congress

The interior of the “Glass Palace” on June 2, 1880, during the Republican convention. Library of CongressAs Chief of Staff to Major General William S. Rosecrans, Garfield maintained a duplicitous correspondence with the War Department, regularly criticizing his commander’s decisions. By December 1863, he had happily traded his military uniform for civilian attire, stepping down to claim the congressional seat he had won a month earlier – despite never campaigning. A coincidence that followed him for the rest of his career.

Imagine with me the 1880 Republican National Convention, a spectacle that resembled nothing so much as your Uncle Earl’s third wedding — you know, the one where the bride’s ex showed up with a parrot. Politicians with handlebar mustaches that could qualify for their own congressional districts swarmed Chicago’s streets, backstabbing each other with the precision of knitting circle gossip. Shouting matches erupted with the frequency and predictability of grandpa’s digestive complaints after Thanksgiving dinner.

To understand the political division within the Republican Party—picture two squabbling siblings fighting over the last cookie—you have the Stalwarts and the Half-Breeds. The Stalwarts were the ‘old guard’ of the Republican Party, those crusty uncles who still insist on wearing three-piece suits to the beach. They clutched on to their patronage jobs like pearls and rallied behind Senator Roscoe Conkling from New York—a man with the charisma of a carnival barker and the ethics of one, too. These folks weren’t just fans of the spoils system; they were its groupies, and blackmail was just another tool in their questionable toolbox.

Then there were the Half-Breeds, political mongrels with one paw in reform and the other still happily splashing in the mud puddle of patronage. Their pack leader, the magnificently mustachioed James G. Blaine—whose hair had its own gravitational pull—yapped endlessly about cleaning up government. They sniffed disapprovingly at the corruption wafting from congressmen in fat-cat cities like New York, while never noticing the similar stench clinging to their own coats.

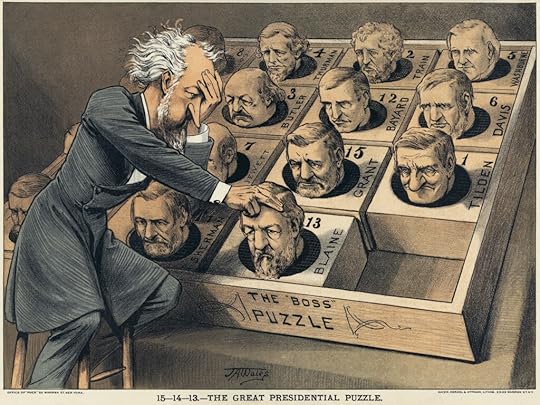

The Nomination No One Saw Coming By Mayer, Merkel, & Ottmann: lithographers James Albert Wales: artist. United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division

By Mayer, Merkel, & Ottmann: lithographers James Albert Wales: artist. United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs DivisionJust when everyone thought they’d be stuck with a Stalwart or Half Breed (an idea as exciting as choosing between oatmeal and oatmeal with butter), James A. Garfield unleashed a speech so stirring it could’ve made a statue weep. Handkerchiefs dabbed at eyes everywhere. The awkward plot twist? He promoted John Sherman, fellow Ohio Senator, current Secretary of the Treasury, and his friend.

And nobody was exactly chomping at the bit to resurrect the political corpse of President U.S. Grant, whose second term had ended with the stench of scandal so pungent you could practically see corruption fumes wafting from the White House windows.

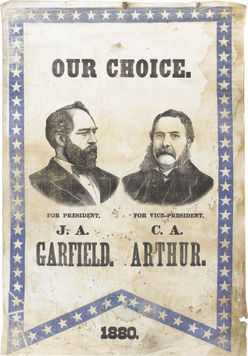

After all the fighting and drama, Garfield was nominated on the 36th ballot. It was like picking the least popular kid for the soccer team, and everyone thought, ‘Well, I guess he’s our best option!’ His calm demeanor and military background made him the perfect compromise candidate, and suddenly, without trying (again), he was the one wearing the big hat.

Front Porch Campaign African American Civil War veterans visited James A. Garfield’s Mentor, Ohio, property during the 1880 “front porch” presidential campaign. The Garfield home is visible in the background. Garfield was one of the few Republicans still openly talking about race and civil rights as late as 1880. NPS

African American Civil War veterans visited James A. Garfield’s Mentor, Ohio, property during the 1880 “front porch” presidential campaign. The Garfield home is visible in the background. Garfield was one of the few Republicans still openly talking about race and civil rights as late as 1880. NPSInstead of galloping across America like today’s candidates, Garfield hatches a peculiar plan: he plops his presidential campaign right on his front porch in Mentor, Ohio. Why this porch-based political experiment? Garfield had some health hiccups and had been wrestling with a nasty bug. He wasn’t keen on bouncing around in dusty train cars and eating greasy takeout. His brilliant solution? Bring the people to him. It also allowed him to connect with voters in a more personal way, because nothing says ‘trust me with nuclear code’ like letting strangers sit in your wicker lawn chair and drink lemonade.

People from all walks of life flocked to Garfield’s home. Farmers, families, Civil War veterans, and curious onlookers came to hear him speak and shake his hand. It was like a mini-festival, with everyone invited. Notable Republicans and campaign managers were there too, helping to strategize and gather support. Think of them as party planners, ensuring everything ran smoothly while Garfield charmed the crowd. Reporters and journalists were also on hand to cover this unusual campaign style.

From his front porch, Garfield tackled weighty matters like civil service reform, economic policy, and educational initiatives, but framed them through the lens of ordinary Americans’ daily struggles. He’d often pause mid-speech to share a humorous tale about his childhood or quote folk wisdom, transforming complex political discourse into kitchen-table conversation.

The strategy proved remarkably effective. As autumn leaves fell and election day approached, the steady stream of visitors departing Mentor carried not just pamphlets and campaign buttons, but also a sense that they’d met not a politician but a neighbor who understood their concerns.

Where Was Chester? Chester Alan Arthur- National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. Harry Newton Blue.

Chester Alan Arthur- National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. Harry Newton Blue.Chester A. Arthur– a man whose magnificent walrus mustache preceded him in any room- was a prominent figure in the Republican Party, known for his affiliation with the Stalwarts faction. At the time of Garfield’s nomination, Arthur served as the Collector of the Port of New York. This position afforded him significant influence, connections, and the ability to wear absurdly opulent suits without a hint of irony. As Roscoe Conkling’s right-hand man, Arthur navigated party politics with the precision of a socialite selecting the perfect pair of riding gloves.

Although Arthur was not the leading campaign strategist–preferring to spend his evening enjoying the finer things in life–he nevertheless proved instrumental in corralling Stalwart supporters behind Garfield. With the panache of a circus ringmaster, he orchestrated delicate peace talks between the stuffy Stalwarts and the reform-obsessed Half-Breeds, who mixed like oil and vinegar at a church picnic.

Arthur’s true genius emerged in fundraising, where his New York Connection, cultivated during legendary midnight feasts at high-priced restaurants, opened wallets faster than a pickpocket on payday.

As Garfield held court on his front porch, Arthur took to the road. He delivered speeches in his oddly high-pitched voice that belied his imposing physical stature, charming Stalwart cronies with inside jokes about Conkling’s vanity and impromptu Shakespeare recitations. Arthur’s flamboyant presence, always impeccably dressed despite the campaign’s trail’s rigor, somehow convinced party loyalists that the reserved Garfield might not be such a bore after all.

A Close Election

The 1880 presidential election revealed a nation still nursing its Civil War wounds. Garfield’s opponent, the Democratic General Winfield Scott Hancock, had earned bipartisan admiration through his battlefield valor. As Americans cast their ballots, they faced a country beset by economic turmoil and scandal-plagued administrations. The electorate grappled with competing visions for government service, tariff policies, and how-or whether- to complete the abandoned promise of true reunification with the former Confederate states.

In the end, Garfield secured 214 Electoral College votes to Hancock’s 155, a margin that belied the true closeness of the contest. The popular vote revealed an even narrower divide: Garfield received approximately 4.4 million votes (48.3%), while Hancock received 4.2 million (47.6%). With less than 10,000 votes separating the candidates, fewer than the population of a small city, the election outcome was a coin toss to the very end.

Side Note: The final count is often debated, but everyone agrees that Garfield won by the smallest of margins. The numbers I provided are from the National Parks Service and the National Archives.

Taking Center StageGarfield’s elation mingled with a sobering awareness of duty. The Oval Office loomed before him—not merely a prize to be won, but a pulpit from which to champion reform and confront the nation’s ills. Contemporary accounts suggest he drew quiet satisfaction from the voters’ endorsement, viewing their ballots as both affirmation and directive. Yet even as champagne corks popped, his mind cataloged the fractures within his own party and the obstacles that would inevitably arise. This characteristic balance of optimism and pragmatism—celebration tempered by foresight-reveals the contemplative man behind the politician’s smile.

On March 4, 1881, James A. Garfield took the oath of office amid an atmosphere electric with anticipation. Standing before the gathered crowd, he delivered an inaugural speech that wove together aspirations of national healing and governmental transformation—a blueprint for the administration he envisioned.

Time, however, was not on his side.

Click here to read his Inaugural Address.

Final ThoughtsI’ve always found President Garfield’s life story deeply moving. His rise from poverty to presidency reads like something out of a storybook-a farm boy who worked his way through college, became a respected scholar and soldier, and eventually ascended to the nation’s highest office.

Tragically, Garfield’s narrative was cut short just as it began. His assassination represents such a pivotal moment in American history that we must examine it thoroughly; the cast of characters surrounding his death, the catastrophic medical decisions that followed, the courtroom battles over his assassin’s sanity, and how those 199 days between inauguration and death transformed not just a presidency, but a nation’s understanding of itself.

Until next time, Keep Reading and Stay Caffeinated.

Subscribe below to stay up to date on myths, legends, mysteries, and the chaos of history.

FacebookThreadsInstagramAmazonXYouTube

If you’re looking for your next favorite read, I invite you to check out my book, The Raven Society. This spellbinding historical fantasy series takes us on a heart-pounding journey through forgotten legends and distorted history. Uncover the chilling secrets of mythology and confront the horrifying truths that transformed myths into monstrous realities. How far will you go to learn the truth?

The Writer and The Librarian (Book 1):

Signed copies at:

https://rlgeerrobbins.com/product/the-writer-and-the-librarian-the-raven-society-book-1/

Explore more blogs here:

November 13, 2025The True Origins of Thanksgiving: Myths and RealitiesFrom Sarah Hale's famous nursery rhyme to Lincoln's proclamation, Roosevelt's date-shift, and the Pilgrims' harvest feast—these seemingly disparate threads of … July 4, 20254th of July: From Patriotism to CommercialismThe cost of Independence was not free. It was paid for by the sweat and blood of over 376,000 lives. … April 27, 2025The Surprising History of Maypole RibbonsDid you know you could have a Maypole with no ribbons and still celebrate May Day? And still be historically … October 10, 2023Unique Gravestones: Tales Behind Famous MonumentsGravestones reveal a great deal about the deceased and the living. Let's explore some of the more unique ones that …Sources:

The Front Porch Campaign of 1880 (U.S. National Park Service)

How Might the 1880 Election Have Gone Differently? (U.S. National Park Service)

Chester A. Arthur | The White House

Chester A. Arthur: Campaigns and Elections | Miller Center

The post Exploring James A. Garfield: The Beginning of a Tragic Tale appeared first on Chasing History.