A Simple, Hard Truth and A Giveaway

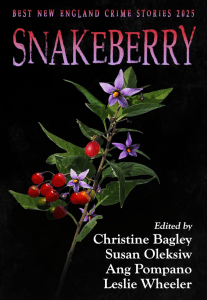

Snakeberry: The Best New England Crime Writing came out earlier this month and I’m going a giveaway to celebrate!

Snakeberry: The Best New England Crime Writing came out earlier this month and I’m going a giveaway to celebrate!

Snakeberry is a great anthology, a labor of love, put out every year in celebration of New England crime writing. This year’s edition has some great Maine representation: Bruce Robert Coffin, Brenda Buchanan, Mo Moeller, and me.

If you write crime stories, be sure to submit next round. Submissions usually open in January.

The collection never disappoints and this year is no exception. To celebrate, I’m going to share my story that was included in the 2023 collection: Wolfsbane.

Read the story and let me know what you think. One lucky commenter will be selected to win a copy of this year’s collection so check back in tomorrow morning to see who it is. And if you don’t get selected, you can purchase a copy HERE. As Dick Cass always says, “Books make great gifts.”

“A Simple, Hard Truth”

By Gabriela Stiteler

Originally Published in Wolfsbane: Best New England Crime Stories (2023)

You get thirty-six years into teaching and you think you know it all.

And then something happens to disrupt the equilibrium.

For example, fifteen years or so ago I had this kid, a smart kid even though I’m not supposed to say that. She was the sort of kid who, when reading Hamlet, called Queen Gertrude “Trudie.”

She made a compelling case that maybe Trudie knew about the poison. That she, like Ophelia, was trapped and poison was the way out. In our unit on Steinbeck, we talked a lot about loneliness and friendship and the way a person can corrode. She had been offended that Curley’s Wife, who was a not a good person, didn’t have a name. She said it was manipulative. She said, “No wonder she corroded.”

I tried to point out that’s what most writing is. Manipulation. A way for us to justify things to ourselves and each other. Things we don’t really understand.

I still think about that kid from time to time.

And again, five years ago I had one kid I didn’t like. Part of me feels bad saying it because I’m not supposed to dislike any of the kids I teach. But he called a girl one of the worst things you can call a girl when she offered up an opinion different from his. And he sprinkled racial slurs into conversations like salt.

He had his reasons.

Abusive dad. Absent mother. And, you know, society. We condition our boys to bottle everything up and then we shake and shake and shake and wait to see what happens.

At the end of the year, he said I was the best teacher he ever had. A statement that kept me up at night. That kid is off in the world now and I try not to think too much about what sort of damage he might be doing.

Then again, he might have turned out just fine.

This past March, I experienced another disruption.

In my third block, the one right after lunch, the kids were preparing for their capstone project, an essay about a life lesson learned. It’s one of those tasks they have to finish in order to get that slip of paper that allows them to walk across the stage and enter the great beyond. In my thirty-six years, I’m proud to say, never once has a kid not earned this credit for my course.

Not even that kid I didn’t like.

Anyway, third block was quiet until Amy, who usually kept to herself, shook things up. She asked, and I still remember because I wrote it down, “Can a life be made less valuable if a person does wrong? Can everything really be forgiven?” It wasn’t where I’d imagined things going, but sometimes it’s worth it to let the train go off the rails. I posed the question to the class and sat back and listened and thought to myself that these kids might just be alright.

But the next day Amy, who asked that question and set us off down a discussion with no clear answer, disappeared from school. Now there are some kids that drop in early spring when they realize they’ve sunk themselves too deep in missing work and low grades. When they realize the year is past the point of salvaging. But not this kid. Until that question in class, she had struck me as the sort that is afraid to breath too loudly, afraid of taking up too much space.

Besides, all her graduation requirements were stacked neatly, waiting. I know because I checked. She was down to a handful of hoops, easy hoops. All she had to do was jump.

Why then, had she disappeared?

I gave it a week before I started asking around. There were two students in particular who could be depended on to be in the know: Jackie Sullivan with a pixie cut and sullen expression and Lauren Reed with pink hair and three nose rings. All it took was two donuts from Tony’s and an invitation to stay after school.

They spilled right away.

“Believe me,” Lauren said, ignoring the donuts. “Amy has her reasons for not coming.”

Jackie nodded and selected a jelly-filled number dusted with powdered sugar.

“Her mom’s sick,” Lauren went on, shooting a quick side-look to the door and lowering her voice. “You know. Real sick. And she’s got her little sisters…”

The way she said it, stretching out the word sick, I picked up quick. Amy’s mom was the sort of sick that looks half-dead and pops pills. The kind of sick that can kill a person. The sort of sick that hit my community hard and showed no signs of relenting.

Lauren watched me with a shrewd expression, making sure the information took root.

“You know?” She repeated.

I nodded.

“It’s too bad about her dad,” Jackie said. She’d taken one delicate bite of the donut and had placed it on a napkin at the center of the desk.

“Stepdad,” Lauren corrected. “Nice guy. He tried to bring them to church sometimes. The Catholic one.”

“Saint Margaret’s,” Jackie murmured, continuing that nod.

Another stretch of silence. The stepfather I knew. A stocky man with meaty hands and dimples. He dropped the kids off and was the one who came for conferences.

A good man, by all accounts.

“He helped us with some plumbing,” Jackie said. “My dad was shocked when he found out.”

What happened to the stepdad was no secret. During the last days of winter, what was left of his body was found in the woods with a hole from a shotgun in his chest, his face picked apart by animals. I’d never touched a gun in my life, but I imagined that shotgun wound to be especially gruesome. The police had looked into it and ended up writing it off as one of those tragic accidents. The man was dressed in dark brown and they figured he was clipped by a hunter.

Amy had shown for school the day after the gruesome discovery, stoic as hell.

Lauren was examining her chipped blue nail polish. “So Amy and her sisters are left with their mom.”

A mom who, according to these two, was slowly dying from those little pills she couldn’t stop taking. Addiction being an illness that can corrode.

Which explained a lot. We live in a small community in central Maine that is slowly dying out. At our center is a half-empty historic downtown surrounded by farmland and crisscrossed by the interstate and a muddy river. We’re bound together by all of the stories we know about a person. By the way we’ve seen similar paths worn down over time. And Amy’s path was clear. Without her stepdad, she would have to stay home and work maybe at the gas station or maybe at the bank.

If she didn’t, her sisters would be taken in by the state.

It was a simple, hard truth.

I made small talk with Lauren and Jackie until they ran out of things to say. At the end of the day, they were good kids. Hardworking and mostly kind. They’d be alright. But that’s what I told myself about most of them. It’s the only way a teacher can sleep at night.

As I watched them make their way down the hallway towards the doors, I couldn’t stop thinking about Amy.

I understood that survival was the most basic of human needs and trumped graduation requirements. But I still believed that a degree, that a piece of paper, might set a person on a different path. Besides, it was my calling, getting kids to tell their stories. Holding space for them to be heard.

It was that misguided optimism that had me showing up at Amy’s address one Saturday morning in early spring when the crocuses were starting to pop, golf ball sized bursts of purple and white. Her trailer was a robin’s egg blue and overlooked the on ramp to 95 going north. The yard was half marsh and half brown patchy grass. The driveway was all mud and the roof was covered in a thin coat of moss.

Before I got out of my car, I popped a Tums from the bottle I kept in my glove compartment. My stomach was churning from too much coffee and not much of anything else.

Dan, who had died six years ago from the sort of cancer that eats a person from the inside, had been big on breakfast. Pancakes on Saturdays with syrup he tapped from woods that ran behind our house or a blueberry compote from the raised bed he tended with the care of a devoted retiree. A raised bed that had grown feral in the time that passed between then and now.

My doctor had been telling me to cut back but old habits were hard to kick.

The mom, who might have been named Donna, was sitting on a rusted metal glider with a pressed glass ashtray on her knee. She was wearing a faded yellow terry cloth bathrobe and a menthol cigarette was hanging out of her mouth.

“Morning,” I said, waving.

She blinked at me a few times before nodding.

“Amy here?” I asked in my friendliest voice.

She continued to stare at me as she took a long drag of the cigarette. In that bright morning light, she was almost beautiful, faded and soft at the edges like the petals of a daffodil.

“I’m Mrs. Murphy. Her English teacher.”

She took another drag. “I know who you are. What do you want?”

She swallowed her rs, like true Mainers do and eyed me with red-rimmed, tired eyes filled with distrust.

I shoved my hands into my pocket and pulled out the folded paper I’d brought. “I wanted to give Amy her last assignment. The one that’ll get her the credit for the class.” I unfolded the paper and held it out to her. She stared at it and it trembled in a slight breeze.

After a minute, I pulled it back.

“Look,” I tried again. “She’s a good kid and I wanted to see how she’s doing.”

The woman’s eyes narrowed slightly but that answer seemed more palatable. “If you ask her, she says fine. I don’t think she is. Christ knows I wish she would cry sometimes. Didn’t do it after they found his body. And she’s not doing it now. Just stands there and takes it all in.”

I didn’t move, waiting. What for, I don’t know.

She went on, in what sounded like a rehearsed litany, “Even as a baby she didn’t cry. Not when she was hungry. Not when she was tired.” She took another long drag, still staring at me. “I told her to go back to school. I told her to finish. I never did and look where it got me. That’s what I said to her. But she won’t.”

She laughed then, unexpectedly. It had a brittle, fragile quality, her laughter. She stopped abruptly, her eyes flicking to some point beyond my shoulder.

“I’m here,” Amy said. She was standing at the door on the side porch, clutching a paper towel, staring at her mother, expressionless. She was small with dark hair and pale skin. She was the sort of kid who was good at slipping through the cracks.

I cleared my throat and forced a smile. “Hi, Amy.”

Her brow furrowed for a second, the way it did when she was deciding between two options. I’d seen it enough in class. Which essay topic. Whether or not to raise her hand. If she wanted to take half of my sandwich that day she came in during lunch. In the end she did, eating the thing in silence. Not meeting my eye.

Teachers, the good ones, know to read nonverbal cues like stage directions. What kids don’t say can be just as revealing as what comes out of their mouths.

And Amy, standing there on that porch with the filtered sunlight from a tall, untrimmed elm, had a look of resignation to her that just about broke my heart.

“Come inside,” she finally said before turning and letting the screen door swing shut.

Her mom went right to staring at the highway ramp. I was already forgotten.

Out back, a small shed was rotted away at the bottom and padlocked shut and the stepdad’s truck with a hitch and a flat sat next to it, surrounded in about an inch of water.

I tried to remember the last time it rained.

I followed up the sagging porch was sinking into the marshy lawn, the steps held up but cinder blocks that were half-sunk. Inside, the galley kitchen was spotless but tired, with peeled linoleum floors and cabinet doors that hung crooked. It smelled like bleach and coffee.

I stood on the rug near the door, worried about leaving muddy traces. The water had soaked through to my socks. “I came because…” I began.

“I know,” she interrupted, gesturing to an open window surrounded by busted vinyl blinds. “Can I get you some coffee?”

Christ, and my doctor, knew I didn’t need coffee. My stomach was rebelling against chalky tablets I’d swallowed. But I nodded.

She turned on the electric stove, the coiled burner turning red, before placing a kettle on it. She took two chipped mugs from a shelf, scooped three tablespoons of generic instant coffee into each mug, slid the powdered creamer over, and then turned to stare at me, waiting for the water to boil.

I unfolded the paper again and put it on the counter next to her, pressing down the little creases.

“It’s our last essay,” I said. “I want to hear what you have to say.”

It wasn’t the way I planned to pitch it. I think until the moment I saw her on the porch I really believed I’d get her back in the classroom. That I’d get her to walk across the stage. But looking at her, I knew I was too late for any of that.

She stared at me, chewing on her bottom lip. Not speaking.

The kettle whistled and she poured the water over the grounds and stirred. Three times to the left. Three times to the right. She sprinkled creamer in her cup and stirred again.

“Do you really?” She asked, sounding almost angry.

“I do,” I said. My voice scratched and I felt suddenly and unexpectedly vulnerable. I couldn’t say why this paper felt so crucial. But it was apparent that it was. Call it a teacher’s intuition. Sometimes I could see things kids needed, things they didn’t know. And right then, I could tell she needed to write that essay.

Not that I could put any of it into words.

She lifted her mug and leaned against the wall behind her.

I forced myself to take a sip of the coffee she made, swallowing a bitter mouthful. I could make out the sound of the television down the hall and two little voices. There was a box of cereal on the counter and two bowls and two spoons. Waiting to be filled.

She stared at the paper and nodded slowly. “I’ll get it to you.”

I put the cup back on the counter and smiled.

She nodded again and I took it as a dismissal and left, not entirely sure how I felt.

Two weeks later, the school was mostly empty when I arrived and I made my copies and got a cup of coffee I knew I shouldn’t drink. I said hello to Dennis, a math teacher, a man I’d known for twenty-six years who was wearing a bowtie, like he always did. And I waved at Joe, who was armed with a spray bottle of Krud Kutter and doing the rounds to make sure the bathrooms had been cleaned. He was vigilant about graffiti.

I cracked my classroom windows and looked out over the football fields. My classroom was prime real estate. Thirty-six years will get you that much. The morning sky was gray and rainy and it smelled like wet earth. I left the fluorescent lights off.

I wrote the date on the whiteboard and started wiping my desks down with cleaner. Usually I spent my mornings thinking through my lessons, through the laundry list of kids I want to check in with, through any loose ends from the day before. I heard Amy coming before I saw her. The squeak of wet sneakers on linoleum. The tentative knock at the door. I don’t know how, but I knew it was her.

“Come in,” I said.

She came in, her dark hair damp and pulled back into a tight ponytail. She was wearing a red polo tucked into wrinkled black pants, her nametag askew gripping a folder.

I smiled. “Good morning,” I said and gestured for her to sit down.

She came and sat and she placed the folder on my desk and stared at it.

“Have you eaten yet?” I asked. They never ate breakfast, these kids.

She shook her head.

I opened the top left drawer and took out an orange and a granola bar and a small plastic bottle of water. I placed each in front of Amy in a tidy row.

“How are your sisters?” I asked.

The fat in the cream I’d put in my coffee was beginning to harden at the top, like a delicate sheet of ice. I forced myself to take a sip and waited. I understood kids in the morning. I knew how to hold silences, to create space for whatever they needed to say, to not say.

“Managing,” Amy said, never taking her eyes from the folder.

“And your mother?” I asked, though I wasn’t really interested.

She shrugged, a quick jerk of the shoulders. “Look, I’ve got to go to work. I did that essay. You wanted to hear what I had to say.” She pushed the folder towards me. “Go ahead,” she said. “Read it.”

The way she said it, was forceful and unexpected. It almost sounded like a challenge.

By this point, the smell of the coffee had crawled into my nostrils and I felt like I might be sick. My palms were damp from sweat and too much caffeine. Very few students liked to watch while I read something they’d written. “Now?”

She nodded and I put the cup down and carefully opened the folder, taking a neatly typed paper out. Four pages double-spaced. About two thousand words. No title. No name. No date.

I slid my glasses on and gave myself a minute to adjust. And then, I leaned back and read, swallowing the lump in my throat. The lump that wouldn’t go away. I’m sure my hands were shaking by the end of it. One or two words had been misspelled and my eyes traced back to them, in need of a distraction, in need of more time. When I looked up, Amy was staring at me. Waiting. And that clock behind her head, was like a metronome.

“Is that what you wanted to hear?” She asked after a minute.

I took off my glasses and rubbed my eyes, thinking. What to say. What not to say.

“The man, the one who died at the end,” I twisted my clumsy tongue around the words. “…He was not a good man.”

She said nothing.

I stumbled on, “What I mean to say is I was glad of the ending. I was glad he died.”

She fixed her eyes on my face, as if to make sure I understood. Really understood what she was saying.

“Look,” I tried again, “I understand why the girl did what she did.” I went on, flailing. “It makes me think about that conversation in class. About the questions you were asking about the value of a life. About goodness and badness.”

Amy was still staring at me, still as the granite breakwaters that jutted out into the ocean, trying to protect what they could against those relentless, beating waves.

I straightened the folder and glanced at the clock.

The hall lights turned on and I could hear kids arriving.

I slid the paper towards her and closed the folder. “And how are your sisters doing?” I asked again.

“They’ll survive.”

“And you, Amy? How are you doing?” I asked at last.

“I’m fine.” She said it like she was trying to convince herself of its truth. “Just fine.”

I wanted to say more but didn’t.

The morning bell rang and with it, voices and lockers and shoes echoed down the hallway.

“So you understand?” Amy asked. She might have been asking for absolution, for forgiveness, for a moment of compassion.

I stared at the folder and then at Amy and thought about that endless series of tomorrows that stretched out before her. I thought about my own life, too. Had I ever been so young and so desperate and so brave?

“I do,” I said and maybe I lied.

Amy nodded again and took the water and the granola bar, tucked them into her bag along with the essay she’d written. And she slipped out of the room, down the hallway, and into the world.

I sat at my desk staring at the coffee I knew I wouldn’t finish and the empty folder and the orange. My students began coming into the room. Some laughing. Some quiet.

END

Remember – Leave a comment about the story and check back in the comments tomorrow morning for the lucky winner.

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 507 followers