AI and “editorial independence”: a risk — or a distraction?

When you have a hammer does everything look like a nail? Photo by Hunter Haley on UnsplashTL;DR: By treating AI as a biased actor rather than a tool shaped by human choices, we risk ignoring more fundamental sources of bias within journalism itself. Editorial independence lies in how we manage tools, not which ones we use.

When you have a hammer does everything look like a nail? Photo by Hunter Haley on UnsplashTL;DR: By treating AI as a biased actor rather than a tool shaped by human choices, we risk ignoring more fundamental sources of bias within journalism itself. Editorial independence lies in how we manage tools, not which ones we use.Might AI challenge editorial independence? It’s a suggestion made in some guidance on AI — and I think a flawed one.

Why? Let me count the ways. The first problem is that it contributes to a misunderstanding of how AI works. The second is that it reinforces a potentially superficial understanding of editorial independence and objectivity. But the main danger is it distracts from the broader problems of bias and independence in our own newsrooms.

What exactly is “editorial independence”?The first thing to note about editorial independence is that, like objectivity, it can never actually be fully achieved.

Just as true objectivity is a chimera — and what we actually do is try to remove and reduce subjectivity from our reporting — the idea of being entirely independent of the world outside the newsroom is a myth.

Our choices of story subjects, angles, questions and phrases are all influenced strongly by external forces ranging from the news agenda as a whole and the human and source material we have to work with, to our training and upbringing, the medium we are working in, the tools that we are using, and the colleagues that we work with.

So when we use AI as part of the production process, it’s important to establish exactly how that affects independence in relation to those other forces.

Using AI to generate questionsThe example of AI challenging editorial independent given in the BBC guidelines is using it to provide questions for interviews, because, it says:

“there is a risk that an AI generated line of questioning is not based human reasoning [sic] and could be biased. Reliance on using AI in this way can risk increasingly homogenous output and undermining editorial skills.”

There is some truth in this but two major flaws:

The suggestion that AI-generated questioning is “not based [on] human reasoning”The phrase AI “could be biased” Image generated by ChatGPT. Its suggestion of an AI-generated question is cliched because it is based on recurring human behaviour, and because a counter-bias hasn’t been provided in the prompt.The myth of AI’s non-humanity

Image generated by ChatGPT. Its suggestion of an AI-generated question is cliched because it is based on recurring human behaviour, and because a counter-bias hasn’t been provided in the prompt.The myth of AI’s non-humanityA common myth about AI is that it couldn’t possibly do the things that define us as human. This myth suggests that the workings of artificial intelligence are entirely separate from human nature.

It is a comforting myth because it allows us to feel protected from the very real challenges that AI presents — not just challenges to our work, but to our identity. It allows us to ignore the very human flaws that AI reflects, when trained on our output.

Generative AI’s large language models work by essentially predicting the next word in a sequence of words — a prediction based on training on human writing.

When prompted to generate questions for a journalist, a generative AI algorithm will therefore provide a response that predicts what a journalist would write based on what journalists have written before.

So we can debunk the idea that AI-generated interview questions are “not based on human reasoning”. Quite literally: AI is trained on the results of human reasoning.

In fact, genAI algorithms are trained in a very similar way to journalists themselves. Like large language models, we take in lots of journalism, learn the ‘patterns’ of the questions that journalists tend to ask, and ‘translate’ that to a particular situation.

On that basis, an argument could equally be made that learning from previous journalists’ questions also risks compromising our editorial independence — that, in the words of the guidance around AI, it “can risk increasingly homogenous output”.

And you’d be right.

But we understand that there is always a tension between being entirely independent, and working within a set of unwritten rules that help journalists, colleagues and audiences to understand each other. Negotiating that tension is a core skill of a good journalist.

A new interaction with informationA similar example is provided in the way we read books and guides on journalistic interviewing, or speak to other reporters, to inform our question generation process. This, it could also be argued, “challenges editorial independence” because it makes us reliant on guidance from an external actor (the author).

But we don’t argue that — in fact, we encourage people to get input from books, guides and other journalists.

A major revolution of AI is the way that it provides a new way to interact with information from books, guides, and other writing on a subject.

So when we ask ChatGPT for interview questions, as well as millions of previous questions, it is ‘reading’ countless books, tutorials and guides to interviewing, and translating that information into a response.

While AI does have the potential to deskill journalists, then, it can also do the opposite. It all depends on how it is used.

AI isn’t “biased” — it will have biases (as will you)What about the second flaw with the guidance: the idea that AI “could be biased”?

I’ve already written about why I’m no longer using the phrase “AI is biased”: it misrepresents the nature of that bias by anthropomorphising AI. The biases of AI are statistical and highly variable, and not the same thing as when we describe a person as “biased”.

In the context of the guidance on editorial independence, “AI is biased” positions it as equivalent to a human source that has their own agenda, or an interfering media magnate. Large language models are unlike either of these things.

Why I’m no longer saying AI is “biased”

By emphasising the bias of AI, the guidance allows us to ignore other biases involved in question generation — particularly institutional and demographic biases.

The homogeneity of journalists’ background and training is just one bias that we know “can risk increasingly homogenous output”. Our reliance on official and other easy-to-reach sources is another bias. There are many more.

Objectivity in journalism is about recognising and taking steps to counter those biases through the methods that we use, such as the questions that we ask, seeking alternative perspectives, and what we do with the answers that we get.

The same applies to AI.

It may be better, then, to treat AI as just one of those sources of bias, and explore similar methods that improve objectivity — not least the applications of AI in identifying biases and looking beyond your own limited experience.

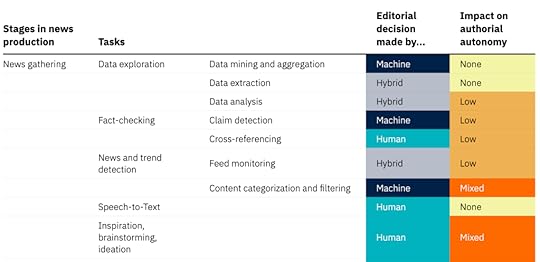

The human element isn’t generation, it’s selection (and development) This “impact matrix” by Katharina Schell lists tasks involved in news gathering, “categorising them by the role of human, machine, or hybrid decision-making and their respective impacts on editorial and authorial control. Tasks with a high impact on autonomy, such as AI-driven story generation, require the highest scrutiny to maintain ethical standards, transparency, and journalistic integrity”

This “impact matrix” by Katharina Schell lists tasks involved in news gathering, “categorising them by the role of human, machine, or hybrid decision-making and their respective impacts on editorial and authorial control. Tasks with a high impact on autonomy, such as AI-driven story generation, require the highest scrutiny to maintain ethical standards, transparency, and journalistic integrity” Perhaps the mistake at the heart of the guidance on AI on editorial independence is to conflate AI with automation.

If we automated the question generation stage in a story it would indeed “risk increasingly homogenous output and undermining editorial skills” — regardless of the technology used.

But AI is a tool, not a process. How we use that tool involves a range of factors. These include:

How we design prompts (including augmenting prompts with our own questions or previous questions)How we iterate with responsesHow we select from responsesEditing, development and adaptationHow AI fits alongside our own processes (are we generating our own questions without AI? Probably yes)Whether AI challenges editorial independence or not depends on how we exercise editorial control through those actions.

If AI is used to generate a wider range of questions than would otherwise be the case, we increase editorial control by providing more options to select from.

If writing an AI prompt forces us to reflect on, and express, what our criteria is for a good question (or a bad one), then this also increases editorial control.

And if reviewing AI responses alongside our own ideas helps us to see bias or homogeneity in our own work, then that critical distance also makes us more editorially independent.

Identifying bias in your writing — with generative AIAutomation — or delegation?

Another way of reading the caution in the guidance is simply “don’t be lazy and delegate this task to a large language model”.

Like automation, delegation is a process, and separate to large language models as a tool. When we talk about automation we are probably talking about something more systematic, more formally integrated into a workflow, and therefore something more likely to have been planned and designed in some way — while delegation is likely to be more ad hoc.

AI does make it easier to delegate or automate editorial decision-making, and the risks in doing so are worth exploring — and clearly identifying.

With every new tool, new skillsets and procedures are needed. Photo by Anton Savinov on Unsplash

With every new tool, new skillsets and procedures are needed. Photo by Anton Savinov on UnsplashWhen seen as acts of delegation or automation instead of the acts of an anthropomorphised “biased” tool, we can start to formulate better guidance.

That guidance can then start to address the new dynamics of the workplace that come as a result of every member of the team managing their own ‘intelligent’ assistants (again, watch out for the anthropomorphism).

Management is the key term here. With management comes additional power, responsibilities and skills. Guidance can draw on that literature, such as when, how, and to “whom” (e.g. role prompting) journalists should delegate or automate editorial tasks.

If we were to delegate a task such as question generation to a colleague, for example, we would need to be confident that they had the right qualities for the task (e.g. scepticism and an aversion to cliche), and had received training in that process (see this “tough interview” involving the BBC’s own David Caswell). We would also check, edit and adapt the results, and provide feedback.

The same principles apply when using AI.

Journalism deals in both speed and depth, and so we might warn against the possibilities of thoughtlessly delegating editorial tasks to AI tools in time-pressured situations, while also encouraging thoughtful preparation for the same editorial tasks.

For example, we might suggest a range of ways that AI can be used as a tool to develop or maintain editorial independence, from question generation using prompts informed by experience and critique, to reviewing questions using the same technology.

A false binaryThe overriding danger in all of this is an arrogance or defensiveness which uses the existence of AI to make us feel superior, and therefore not needing to engage deeply or meaningfully with the concepts of editorial independence and objectivity.

The “AI is biased” argument presents us with a false binary choice whether to use the technology or not, making us feel confident when choosing the human option, instead of asking the better question of “how” AI might tackle or contribute to bias in our processes in general.

Editorial independence is not about the tools that we use — if it was, we would argue that journalists should not use a video camera because it is “biased” towards striking scenes and good-looking sources. Independence is, instead, a collection of behaviours and strategies that inform how we use those tools.

The less we anthropomorphise AI with terms like “biased” and ideas of “challenging” human independence, the more we will see the importance of professionalism in managing large language models, and treating their biases as just one of many that we must negotiate in our reporting — including, crucially, our own.