Raffles, the gentleman thief

The Raffles that concerns us here is the television incarnation as seen in a series of adventures made by Yorkshire TV in 1977. I recently bought a cheap DVD set of the series, not for reasons of nostalgia (a wretched condition) but out of curiosity and whim. I had a vague recollection of enjoying the few episodes I’d seen, and was hoping for another decent Victorian adventure series along the lines of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (1971/1973). Raffles proved to be better than I expected; not quite up to the standards of Granada TV’s peerless adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes stories but thoroughly enjoyable. The production values are better than those in The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, a well-written series with an impressive cast that was nevertheless compromised by a restricted budget. I’m not really reviewing the Raffles series here, this piece is intended to note a couple of points of interest which, for me, added to its pleasures.

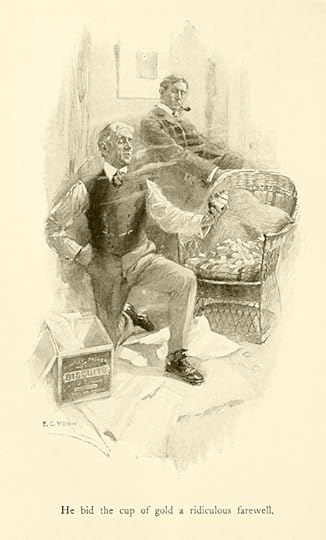

Raffles and Bunny as they were originally. An illustration by FC Yohn from Raffles: Further Adventures of the Amateur Cracksman (1901).

Arthur J. Raffles was invented by EW Hornung, a writer who was, among other things, Arthur Conan Doyle’s brother-in-law. Raffles, like Sherlock Holmes, is a resolute bachelor with a devoted friend and accomplice, but the two men share few other characteristics beyond a talent for outwitting the dogged inhabitants of Scotland Yard. Raffles’ indulgent lifestyle in the bachelor enclave of (the) Albany, Piccadilly, is financed by his burglaries which invariably target aristocrats and the homes of the wealthy. To the general public he’s known as one of the nation’s leading cricket players, a position which gives him access to upper-class social circles from which he would otherwise by excluded. His former school-friend, “Bunny” Manders, is also his partner-in-crime, a position that Bunny is happy to fill after Raffles saves him from bankruptcy and suicide. Conan Doyle disapproved of the immoral nature of the Raffles stories but they were very popular in their day, and they’ve been revived in a number of adaptations for film, TV and radio. George Orwell admired the stories, and writes about them with his usual perceptiveness here, noting the importance of cricket to Raffles’ gentlemanly philosophy of criminal behaviour. I’ve not read any of the stories myself, and I’m not sure that I want now, not when the television adaptations succeed so well on their own terms.

Anthony Valentine and Christopher Strauli.

The TV series was preceded by a pilot episode made in 1975 which saw the first appearances of Anthony Valentine as the dashing Raffles and Christopher Strauli as the fresh-faced Bunny. Valentine and Strauli fit their roles so well it’s difficult to imagine anyone else improving on them, Valentine especially. In the series the pair are supported by many familiar faces from British drama: Graham Crowden, Charles Dance, Brian Glover, Robert Hardy, Alfred Marks, and, in a rare piece of TV acting, Bruce Robinson. Pilot and series were all written by Philip Mackie, and here we have the first noteworthy element since Mackie had earlier adapted six stories for The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, including the one that features Donald Pleasence as William Hope Hodgson’s occult detective, Thomas Carnacki. Raffles is another rival of Sherlock Holmes, of course, albeit a criminal one, and much more of a mirror image of Holmes than the thoroughly villainous Professor Moriarty. Raffles only breaks the law to improve his bank balance, or as an occasional, daring challenge; he regards theft and evasion from the police as a form of sport, and generally deplores other types of crime. Some of his thefts are intended to punish the victim following an infraction, as with the belligerent South African diamond miner who causes a scene at Raffles’ club, and the Home Secretary who makes a speech in Parliament demanding stiffer penalties for burglary. In one conversation about the morality of their activities Bunny suggests to Raffles that his friend is a kind of Robin Hood figure; Raffles agrees before admitting that he never gives his spoils to the poor.

The relationship between Raffles and Bunny is the other point of note. I think it was halfway through the second episode that I found myself thinking “This is all very gay, by Jove!” And this despite my general suspicion of attempts to read a homosexual subtext into every type of Victorian literature, something which has been attempted on many occasions with Sherlock Holmes. (I have a book of gay erotica that includes an extract from Larry Townsend’s The Sexual Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.) Life for the Victorian upper-classes was very homo-social, a constitution that the fiction of the period naturally reflects, and which often causes problems in film and TV adaptations for the many stories which feature few or no women at all. Bearing this in mind, Raffles and Bunny are a pair of bachelors with very little interest in women beyond occasional pleasantries exchanged at mixed gatherings. When Raffles charms the ladies it’s often with the intention of bringing him closer to some expensive bauble that he plans to steal. As the series unfolds, the absence of any external romance that will threaten the Raffles and Bunny friendship becomes increasingly noticeable. When a revelation of past romance with a married woman arrives in the final episode Raffles engineers events so that his old flame is unable to take him away from London and his settled bachelor existence.

Champagne and cigarettes in the steam room. Raffles is smoking despite the notice on the wall asking patrons to refrain.

Then there’s all the visits to the Turkish baths… Our criminal heroes pay regular visits to the place, we even get to see Bunny’s bare bum at one point. I nearly laughed aloud when Raffles is being interviewed by his would-be nemesis, Inspector Mackenzie of Scotland Yard, and Raffles deflects suspicion by declaring that he and Bunny couldn’t possibly have burgled a house when they spent the night together in the Turkish baths. This is all very superficial but an innocent reading becomes increasingly difficult when you know that two years before the series Philip Mackie had also written The Naked Civil Servant, the award-winning dramatisation of Quentin Crisp’s early life. Mackie wasn’t gay but as a writer he could hardly be guileless about the undercurrents in the Raffles and Bunny relationship. It’s easy to see parallels between a life of thieving which can never be admitted to polite society and the love that dare not speak its name.

Raffles and Bunny have a heartfelt conversation in the bedroom.

It’s tempting to go further with this when one reads that EW Hornung based his characters’ relationship on that of Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas. This may indeed be the case but the trail of evidence leads back to a suspiciously vague biography of Hornung by Peter Rowland. Of greater substance is a stage play by Graham Greene, The Return of AJ Raffles, which premiered in London in 1975, and which Mackie must surely have been aware of. When Greene was interviewed by the BBC about his intentions he had this to say:

Raffles and Bunny were, in a sense, the reverse side of the medal of Sherlock Holmes and Watson. That gave me the idea of doing a play on these two characters. […] I’ve brought out what I consider the latent homosexuality in the characters of Bunny and Raffles. I’ve done it only slightly—I mean it’s not by any means a homosexual play. Bunny had been imprisoned with Oscar Wilde for a quite different offence, and so I’ve introduced Lord Alfred Douglas and the Marquis of Queensberry, and also the Prince of Wales, whom I’ve always found a very sympathetic character.

I’m amused that Greene uses the phrase “reverse of the medal” in describing Raffles and Bunny when Teleny, Or the Reverse of the Medal is the title of a very explicit piece of gay erotica frequently attributed (without evidence) to Oscar Wilde. Greene’s play has Bunny, Raffles and Lord Alfred Douglas teaming up to rob the Marquis of Queensbury as revenge for the imprisonment of Oscar Wilde, a laudable enterprise which emulates what we might call the moral immorality of the original stories.

After buying the DVD set on a whim these revelations have been pleasurably surprising. But you don’t have to watch the series for any spurious subtextual reasons, the stories are perfectly enjoyable as they are. Raffles’ exploits begin with small-scale thefts but develop into schemes in which the challenge is as much to outwit the persistent Inspector Mackenzie as to get away with the loot. Hornung’s stories have Raffles and Bunny eventually being caught and imprisoned, with Raffles later going off to die in the Boer War. Mackie ends his series on a happier note, with the pair still blissfully carefree and planning their most audacious robbery yet. There could have been much more of this. It’s a shame there wasn’t.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Enfantômastic!

• Oscar (1985)

• Saki: The Improper Stories of HH Munro

• The Horse of the Invisible

• John Osborne’s Dorian Gray

• “The game is afoot!”

John Coulthart's Blog

- John Coulthart's profile

- 31 followers