A Ticket to Texas: Colonel Rutishauser's Travails at Camp Ford

Captured in the aftermath of the City Belle disaster in May 1864, Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Rutishauser of the 58th Illinois described the elation of his Confederate captors in the aftermath of their successes against General Nathaniel Banks' army.

"They took us to their camp, which was more like a bandit camp, such as I had seen in Italy in previous years, than a military camp," he relayed. "Here I was immediately surrounded by several Rebel officers, all of whom expressed their joy at their victory, which they had just achieved over Banks's mistakes. They mocked this general, called him their commissary, and claimed to have cut off and surrounded the Union army in Alexandria and could now starve them out."

And so began the colonel's lengthy imprisonment; eventually he would be delivered to Camp Ford, Texas, and remained there for nearly six months. Lieutenant Colonel Rutishauser’s account first sawpublication in the November 16, 1864, edition of the Illinois Staats-Zeitungpublished in Chicago. Special thanks to friend of the blog Randy Gilbert whodiscovered and translated this letter from its original German (in fraktur typeno less!) and to Vicki Betts who assisted with the translation.

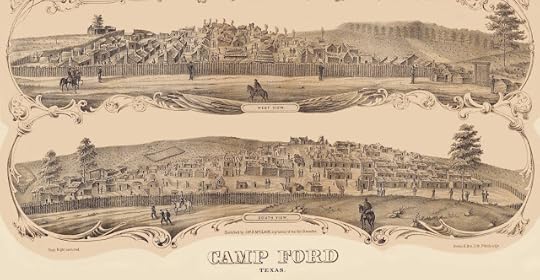

This depiction of Camp Ford, Texas was drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio, a fellow prisoner captured during the City Belle Disaster. (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

This depiction of Camp Ford, Texas was drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio, a fellow prisoner captured during the City Belle Disaster. (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

The brave Lt. Col. Rutishauser of the 58th Illinois Regiment,who was taken prisoner by the Rebels on the Red River last May, and wasrecently exchanged, has shared with us the following interesting account of hisexperiences in the South.

To theeditors of the Illinois State newspaper,

Please allow me to give you a brief account of my capture andmy fellow prisoners' experiences in Texas.

On February7, I was released from McPherson Hospital in Vicksburg with a leave of absence.After recovering somewhat from my illness, I went to Cairo, where I reportedfor duty on April 11to General [Mason] Brayman, commander of the Cairo District, and receivedorders to wait for my regiment, which had been reassigned with the 16thArmy Corps and was not easily accessible to me, as it was in Louisiana.

On the 25th, I reported to General [Stephen] Hurlbut,the corps commander, and received orders and transportation from him, but noopportunity to join the regiment.Three days later, an important dispatch arrived from Washington for General [Nathaniel]Banks and Commodore [David D.] Porter, and I was entrusted with its delivery. Itherefore left Cairo on April 29, and upon arriving in Memphis, by order ofGeneral [Cadwallader C.] Washburn, was given the gunboat Monank (Monarch?)at my disposal. On May 3, I advanced with it to about 30 miles belowAlexandria, when the commander informed me that he could go no further due tothe low water. I therefore considered it best to embark aboard the transportship City Belle, which was following us and had the 120thOhio Regiment on board, in order to deliver my dispatches to the scene.

Colonel Marcus Speigel

Colonel Marcus Speigel120th O.V.I.

However, I had barely been on the ship for 10 minutes when wewere suddenly subjected to heavy fire from artillery and small arms. The secondcannonball destroyed the pilothouse and killed the pilot, and the fourth destroyedthe steam boiler, rendering the ship unsteerable. Many soldiers jumped into theriver to swim to save themselves. The three colonels on board, [Marcus] Spiegelof the 120th Ohio Regiment, [John J.] Mudd of the 2nd IllinoisCavalry Regiment, and [Chauncy J.] Bassett of the 96th U.S. ColoredTroops were killed, along with many other soldiers.

The ship itself was swept ashore by the current on theopposite side of the enemy, whereupon I quickly crawled ashore and fluttered tothe hill under the fierce fire, but without being injured. The boat was sunkinto the shore.

After I wasout of the area of the fire, I destroyed my military orders as a dispatchcarrier and handed the dispatch itself to a private from the 120thOhio Regiment, whom I took along as a companion, intending to carry it on footto Alexandria. During the night, we followed the river for about 20 miles, butour hopes of reaching Alexandria were soon dashed when, unfortunately, weencountered a pile of cotton bales, behind which about 25 Rebels were hidden.They immediately captured us, set fire to the cotton, and marched back the sameway we came.

They took us to their camp, which was more like a banditcamp, such as I had seen in Italy in previous years, than a military camp. HereI was immediately surrounded by several Rebel officers, all of whom expressedtheir joy at their victory, which they had just achieved over Banks's mistakes.They mocked this general, called him their commissary, and claimed to have cutoff and surrounded the Union army in Alexandria and could now starve them out.On the same day, I was taken to Chennyville, but first I was joined by theprisoners of the 120th Ohio Regiment. After marching for seven daysthrough pine forests, bypassing Alexandria, we arrived in Nacatorche(Natchitoches) on May 10th, were transported by river to Shreveport, and fromthere, about 110 miles away, on foot to Camp Ford near Taylor (sic), Texas. Imyself had to be left behind in the so-called hospital in Marshall due toillness.

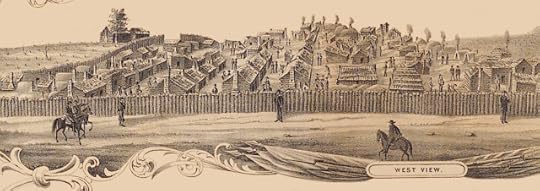

Detailed view of Camp Ford, Texas. Lt. Col. Rutishauser said that the name "camp" was a misnomer "for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed close together. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can." (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)

Detailed view of Camp Ford, Texas. Lt. Col. Rutishauser said that the name "camp" was a misnomer "for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed close together. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can." (Courtesy of Randy Gilbert)After three weeks, and before I had recovered, I, too, had tomarch to Tyler, accompanied by a captured staff officer from General Banks,despite my protests and citing my poor health. Arriving at the camp, I foundthe captured officer prisoners of the 120th Ohio Regiment in a hutthat they had built themselves out of wood and that offered protection from theburning sun's rays, but not from storms and rain.

I am incorrectly using the name "camp" here todescribe the place where we were imprisoned, although it does not deserve it,for it was a six-acre cattle yard enclosed by tall, thick posts placed closetogether. The prisoners are driven into this enclosure like a herd of cattle,and there they are left to make their own beds on the ground as best they can.The camp commander showed so much humanity that he allowed the prisoners, underguard, to fetch bushes and shrubs from the nearby forest so that they couldobtain some protection from the heat of the sun. This humanity, however, wasvery cheap, and in his other treatment of the prisoners, he was so inhumanethat he had some of them shot dead from outside the enclosure without theslightest cause. He is also the author of the order that authorizes any Rebelsoldier or citizen to shoot at will any Union prisoner attempting to escape.

Before I speak further about this enclosure, I must return toour marches. For two days we had nothing to eat except a small so-calledbiscuit, a tuber kneaded together from water and flour. Later, we were givencorn flour in very small quantities and quality. However, since we had nocooking utensils, each of us provided himself with a board on which the flourwas mixed with water in the evening and roasted over the fire without salt.Finally, pork and beef were also delivered, which we stuck on sharpened twigsand roasted over the fire. At night, we slept without shelter, most of uswithout blankets, on the bare ground. I myself was fortunate enough to keep mywatch, which I bartered with a Rebel soldier after a few days for a usedblanket that had been taken from under a horse's saddle. My money was stolen bya Rebel guard on the very first night, as I fell asleep after a weary march.The thief, who returned the empty wallet to me, received no reprimand from hiscommanding officer, Captain Hendriks, 6th Texas Cavalry Regiment,when I complained to him.

The Ohioans fared no better; the night before we arrived atcamp, they were combed and searched by the Rebel guards, and under threat ofbeing shot if they resisted being plundered. At Camp Ford, the men are providedwith cornmeal and beef, which is distributed equally. This, apart from a littlesalt, is the only food available, and it is therefore no wonder that thehospital is full and the sick roam the camp by the hundreds. The prisonerscannot procure vegetables, for even if they have money, access to theseprovisions is blocked. I myself was once granted the privilege of receiving anorder allowing me to bring two watermelons into camp for my own use.

However, afew prisoners of Irish descent, who enjoyed the favor of Colonel Border, wereonce granted the privilege of trading in foodstuffs subject to a tax of 25percent of the value. This tax, it was said, was intended to benefit thehospital. The Rebel Dr. [Thomas W.] Meagher of Tyler, who was in charge of theoperation, never received any of it, so it can only be assumed that the colonelused the money for his own purposes. Mycomrades in the field will do well to remember the names of Colonel J.P. Borderand his adjutant, B.W. McEachem, both of whom treated the prisoners in the mostoutrageous manner, so that if they ever get hold of them, they can pay them inkind.

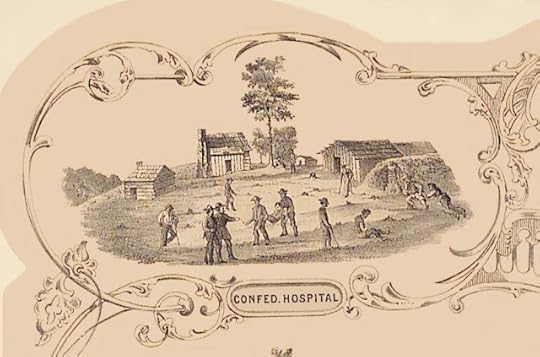

The hospital at Camp Ford as drawn by James McLain of the 120th Ohio

The hospital at Camp Ford as drawn by James McLain of the 120th OhioFrom time to time, some wheat flour also arrived at the camp.It cost 50 cents in greenbacks per pound. Sugar cost $1.75 per pound, pork$1.00, butter $1.75 per pound, a gallon of molasses $6.50 per pound, a quart ofmilk $1.00, and onions $1.00 per dozen. For several days, Col. [George] Sweet [15thTexas Cavalry] has been the post commander. He asked me to take over thesupervision of the camp and gave me the necessary orders. I devoted myattention to cleaning the camp in a military manner, which mainly improved thehealth of the people. I visited the sick, tried to cheer them up, and gave themmy advice as best I could. This is about all that can be done for them. We haveno proper doctors there; The few gentlemen who consider themselves such, butwho understand nothing of medicine, contribute not a little to the increase inthe number of burial mounds. Medicines are also in short supply.

During the course of my duties, I monitored the supply ofrations and discovered a deficit of 8,287 corn meal rations for 3,070 men in 17days. Considering the quality of this food, it is easy to see that theprisoners must have suffered greatly from such deception. I lodged a complaintagainst this injustice and thereby somewhat improved our situation, but I couldnot prevent us from later being given unmilled corn when the mill broke down.Fortunately, we had some good craftsmen among us, whom I immediately employedto repair the mill to protect us from starvation.

Col. Sweet allowed some of his men to go into the woods withthe prisoners to gather brush for the camp and huts, but after a few days, thisprivilege was revoked, as it was considered too inconvenient for the guards toconstantly run into the woods. Indeed, it required the service of two men fortwo hours a day to enable the poor prisoners to seek shelter from the burningsun and the rain, and to grant this is too generous. Such conduct exposes themen's lies when they excuse themselves for not being able to treat ourprisoners better and pretend to give them what they have.

I was almost overwhelmed by my duty, in which I could not beof any significant use to my fellow sufferers, and therefore submitted myresignation, which was granted. It is a sad sight to see about 3,000 men,mostly without blankets, in ragged clothing, and fed as described above,crammed in as we were. Therefore, no words can describe the joy I and 600 of myfellow prisoners felt when we left the camp on October 1st to beexchanged. On the way to Shreveport, we met a wagon train containing clothingand blankets for 1,200 men, which our government, accompanied by two Unionofficers, sent through the Rebel lines to our prisoners. These items will warmnot only many a body this winter, but also many a heart at Camp Ford.

With the 600 lucky ones, I traveled on foot, but at a lightpace, to Shreveport. Here, part of the crew was sent by boat and another partby land to Alexandria. It took us no less than 21 days to reach the mouth ofthe Red River, where we were exchanged. I need not describe the feelingsaroused in the people by the sight of the Star-Spangled Banner. The poor souls,almost all of whom were half-naked and barefoot, were reclothed in New Orleansand thoroughly enjoyed Uncle Sam's hearty rations, so that they would soon beable to devote their services to the country again.

I.Rutishauser, Lieut. Colonel, 58th Illinois Regiment

Isaac Rutishauser (Rutishowser/Rutsehaucer) was born 18 July1810 in Amriswil, Switzerland, emigrated to the US in the late 1850's and wasnaturalized on October 17, 1859. The 1860 census shows him as a saloon keeperresiding in Somonauk, Illinois, a village in northcentral Illinois west ofChicago. He was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 58th Illinoison January 25, 1862, and saw action at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Iuka, andMississippi. “For a long time, he was well and favorably known among our Germanpopulation,” the Chicago Tribune noted. “He was a brave and fearlesssoldier and at the battle of Shiloh he was wounded, taken prisoner, and held sixmonths before he was exchanged.”

The 58th Illinois saw service in the Red River campaignwhen Lt. Col. Rutishauser was trying to join them; this led to his capture May3, 1864. Following his release from Camp Ford on October 1, 1864, he wasdischarged January 27, 1865. “In 1865, he was appointed an Internal RevenueInspector and was legislated out of office in 1869,” the Tribune stated.“In 1873, he was appointed a Gauger which position he filled until 1876 whenthe whiskey troubles culminated. For 4 months past he had been employed in thepost office and had resigned his place, the resignation to have taken place fromthe 1st of November.” He collapsed of apoplexy and died October 23, 1878,in Chicago in the Grand Pacific cigar store of his son-in-law Louis Schaffnerand is buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

To learnmore about the loss of the City Belle which led to Lt. Col. Rutishauser’scapture, click here to read Captain James Taylor’s account in “Disaster atSnaggy Point with the 120th Ohio.”

Sources:

Letter fromLieutenant Colonel Isaac Rutishauser, 58th Illinois VolunteerInfantry, Illinois Statts-Zeitung (Chicago, Illinois), November 16,1864, pg. 1

“IsaacRutishauser,” Chicago Tribune (Illinois), October 24, 1878, pg. 8

“SuddenDeath of a Well-Known Citizen, Chicago Inter Ocean (Illinois), October24, 1878, pg. 8

Daniel A. Masters's Blog

- Daniel A. Masters's profile

- 1 follower