With a European next-gen fighter program in doubt, what would an FCAS collapse look like?

BELFAST — This month key stakeholders in one of Europe’s most highly publicized and troubled defense projects, the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), were expected to sit at a table and hash out their issues. But now such a meeting between German, French and Spanish officials has been put on hold, the latest stumbling block in a development path riddled with obstacles.

“The date of the trilateral meeting has been postponed,” a spokesperson from Germany’s Federal Ministry of Defence told Breaking Defense in a statement today. “The Federal Government continues to strive for the successful implementation of the project. We are in close contact with our French and Spanish partners to determine a new date for this meeting.”

The spokesperson declined to share the reason behind the postponement, but it comes amid political upheaval in Paris as French President Emmanuel Macron prepares to select a . The French Armed Forces ministry and Spain’s Ministry of Defense have not responded to requests for comment at the time of publication.

The delay comes amid troubles and recent eyebrow-raising comments from industry officials that have prompted fresh worry about whether the project will survive at all and, if it should collapse, what would happen to its participants.

According to three close observers of the program, FCAS is not quite dead, and may yet survive to fruition. But should it fail, the blow could strike Berlin much harder than Paris, as the French may have the capacity to push on to their own sixth-generation fighter program alone. As for Spain, there’s an open question.

“I think they [France] probably can” produce a future fighter jet alone, but “it will be expensive,” Douglas Barrie, a senior fellow for military aerospace at the UK-based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) think tank, told Breaking Defense.

As it is, the trilateral program is designed to deliver a replacement for Eurofighter Typhoon and Rafale fighter jets ready for entry to service in 2040. But the effort has routinely faced difficulty as far back as 2021 because of an uncomfortable partnership between Airbus and Dassault, with the latest power struggle between the two sides centering around the French manufacturer’s demand for greater control of the New Generation Fighter (NGF), the actual aircraft at the center of the FCAS family of systems.

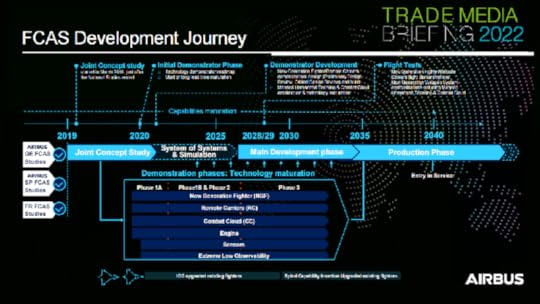

An FCAS development timeline, shared by Airbus in 2022. (Airbus)

An FCAS development timeline, shared by Airbus in 2022. (Airbus)French-based Dassault CEO Eric Trappier has insisted that unless the company is made a “clear leader” for the program, FCAS will be condemned to failure, per Flight Global.

In June, an Airbus executive attempted to describe the problem from his firm’s point of view.

“Clearly, we have observed with this [1B] phase, difficulties in the execution and facing the problem there are different ways to look at it, different types of problem statements,” Jean-Brice Dumont, head of air power at Airbus Defence and Space, told reporters during a company media briefing at the Paris Air Show. At that time he also said that “connectivity, interoperability is a point of today” holding the program back.

Though the leadership dispute between Dassault and Airbus has been an open sore for months, the need to agree to a resolution is heightened by the risk of delay to FCAS Phase 2 — planned to go ahead next year, but with a contract still to be negotiated. The milestone is critical for industry to develop technology demonstrators covering the NGF, its engine, remote carriers, a “combat cloud” and sensors.

The End Is Nigh-ish, And France’s OptionsBarrie said that he would be “hesitant” to write off FCAS “completely,” based on past European fighter programs having survived similar problems. But he added, there is a “risk” that with the current jockeying for position both politically and industrially, when one party “inadvertently” causes another to “throw toys out of the pram,” or walk away in frustration.

He added that political “optics” at the moment, are “lukewarm” in terms of enthusiasm for FCAS from both Germany and France — a scenario that can be interpreted in two ways: Berlin or Paris is attempting to bluff the other, or clear signaling that the program is in “serious trouble.”

Barrie explained, “Which of the two it is, I think we’ll only find out either when the program moves ahead or one of the countries walks away from it.”

A comment from Trappier in September has only added to the sense that a national partner could walk away. Asked whether France could build a next-gen fighter alone, he said simply, “The answer is yes.”

Francis Tusa, a UK defense analyst, noted that Dassault’s planned Rafale F5 upgrade and a notional F6 standard, would set a “pathway” for the aircraft to stay in service until 2060 if necessary. Additionally, he stressed that French engine manufacturer Safran’s deal to codevelop India’s Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) gives credibility to Paris’ capacity to move ahead with a future fighter program alone.

This photograph shows a patrol of Rafale jet fighters seen from the ramp of an A400M aircraft during a rehearsal for the annual Bastille Day military parade on July 14, near the Orleans-Bricy air base some 20 Km (13 miles) from Orleans, central France, on July 3, 2024. (Photo by GUILLAUME SOUVANT/AFP/GUILLAUME SOUVANT/AFP via Getty Images)

This photograph shows a patrol of Rafale jet fighters seen from the ramp of an A400M aircraft during a rehearsal for the annual Bastille Day military parade on July 14, near the Orleans-Bricy air base some 20 Km (13 miles) from Orleans, central France, on July 3, 2024. (Photo by GUILLAUME SOUVANT/AFP/GUILLAUME SOUVANT/AFP via Getty Images)France “may well go solo because of the way that they work hand and glove” with local industry, typically not with other national partners, said Gary Waterfall, a former UK Royal Air Force air vice-marshal.

France could fund a future fighter on its own, the analysts said, in part by securing orders from export nations, especially potential customers in the Middle East.

Barrie pointed to the UAE, which has purchased 80 Rafale jets from France. “I’ve always kind of wondered … whether or not there’s a codicil in that agreement that said, ‘If you were minded to look at a combat aircraft program beyond Rafale, we might have a way to kind of put you in our sphere, on what we do next.’”

Similarly, Waterfall noted, “I think what they’ll [France] be looking for is to have a proliferation of Middle Eastern countries that they can bring along with them and have exports as a way to pay for the development and R&D of it.”

Berlin’s BarriersSimply put, Germany’s options appear less favorable than those of France, according to the analysts.

Tusa pointed out, for instance, that local firm MTU Aero Engines lacks the experience of single-handedly developing a fighter jet powerplant. MTU is part of the Eurojet Turbo GmbH consortium that manufactures the EJ200 engine, equipped on the Eurofighter Typhoon. According to company literature it is also “developing, producing, and providing support” for the FCAS New Generation Fighter Engine (NGFE), in partnership with Safran and Spain’s ITP Aero.

“One has to understand, MTU has not been an engine prime, not even on commercial [aerospace programs] … for 40 to 50 years,” said Tusa. “To go from [making smaller component parts] to … complete a 90-100 kilonewton” thrust capable fighter jet engine, would be a hugely difficult task.

He also noted that if Berlin were to jump ship, it likely wouldn’t find dry land at the rival Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) project currently underway by Italy, Japan and the UK. It appeared clear just last month that GCAP players are at this late stage.

GCAP aims to replace UK Royal Air Force and Italian Air Force Eurofighters, as well as Japan Air Self-Defense Force F-2 combat jets and is wedded to a 2035 entry to service date. Barrie said that because of “where GCAP partners are in terms of the program at the moment, what they don’t want to do is to start to have to renegotiate stuff, introducing somebody else at this point and then slow the program down.”

A Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) core vehicle concept on display at DSEI, London (Breaking Defense)

A Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) core vehicle concept on display at DSEI, London (Breaking Defense)One alternative path that Germany could consider if FCAS fails and GCAP membership is closed off would be to buy GCAP future fighter jets off the shelf once early editions become available. If it “buys enough” GCAP aircraft down the line, local production could then be approved, claimed Tusa.

As a fallback option, Barrie floated the idea of Germany potentially gaining GCAP observer status, with the result that it could let Berlin put its “house in order.”

In this context, Germany would not be a full member of the program and would be unable to make any decisions, but instead benefit from cooperation with other partners. Although GCAP has not used the mechanism to date, Belgium was welcomed by FCAS as an observer nation in 2024 and continues to await full membership.

El futuro del FCAS en EspanaWhile the media gaze concerning FCAS has more often than not been directed at France and Germany, Spain will also be faced with tough decisions if the program collapses.

Madrid in August said it was not going to buy American-made F-35 fighter jets and would instead focus on the acquisition of Eurofighter Typhoons or FCAS fighters.

In September, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez signaled solidarity with Germany in relation to the FCAS industry workshare dispute between Airbus and Dassault, stressing that “conditions that had been agreed in advance” should be upheld, according to Belgian-based Euractiv.

Like Germany, it’s probably too late for Spain to try to jump to GCAP, Tusa said. Though he pointed to recent press reports suggesting Spain may consider buying Turkey’s KAAN next-generation fighter currently in development.

On what happens next for FCAS as a whole, should Paris, Berlin and Madrid, eventually sit down for talks, “I think that there will be resolution of some sort,” said Barrie.

Douglas A. Macgregor's Blog

- Douglas A. Macgregor's profile

- 28 followers