INTERVIEW: with author SenLinYu

Author SenLinyu has been a semi-anonymous force in the speculative fiction fanfiction spaces for years, where they developed their dark and unflinching characterizations and lyrical prose to a rabid readership. Their collected stories have garnered over 20 million downloads.

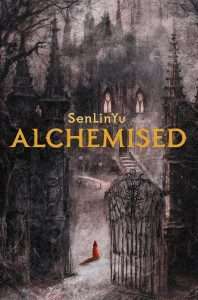

Recently, SenLinYu has stepped into the semi-public spotlight with the release of their new story, Alchemised. The story follows the once-promising alchemist Helena Marino as she comes to terms with her new, war-torn world. The world she once knew, the people she knew… gone. Her abilities were suppressed, and her memories are hidden. “To bring her memories forth, Helena is sent to the High Reeve, one of the most powerful and ruthless necromancers in this new world. Trapped on his crumbling estate, Helena’s fight… For her prison and captor have secrets of their own… secrets Helena must unearth, whatever the cost.”

Recently, SenLinYu has stepped into the semi-public spotlight with the release of their new story, Alchemised. The story follows the once-promising alchemist Helena Marino as she comes to terms with her new, war-torn world. The world she once knew, the people she knew… gone. Her abilities were suppressed, and her memories are hidden. “To bring her memories forth, Helena is sent to the High Reeve, one of the most powerful and ruthless necromancers in this new world. Trapped on his crumbling estate, Helena’s fight… For her prison and captor have secrets of their own… secrets Helena must unearth, whatever the cost.”

Alchemised is written as a story of deep contrasts: SenLinYu’s storytelling is both gentle and tender, yet sharp as a razor, showcasing ruthless moral quandaries while still maintaining its humanity. Alchemised is a story that embodies what grimdark is: the gray. The difficult choices with ambiguous morality and little patience for heroes. All of this is set against a Gothic background and world that is, in many ways, a character in its own right.

I was privileged to talk with SenLinYu, an author I have been reading for years and greatly admire as a lover of the morally ambiguous. In this conversation, we speak to Senlinyu about their transition from an anonymous writer to a published novelist, how their creative environment and personal rhythms shape their work, and how they balance the absolute savagery of the story with quieter, more reflective moments.

[GdM] Can you tell me about your new novel, Alchemised?

[SLY] Alchemised is a bit of a genre-bending gothic war novel about a healer with amnesia kept prisoner in a deteriorating mansion while her captors try to discover what secrets her memory might be hiding, both from herself and from them. It’s a nonlinear story that focuses on aspects of war that tend to be written out of the narrative.

[GdM] You started your writing career in anonymous fanfiction spaces. However, with the release of Alchemised , the boundary between what is private and public must have shifted. How are you protecting what you have chosen to remain private?

[SLY] When I started writing, part of the appeal fandom was the default of pseudonymity. Not because I was trying to hide, but because I wanted my work to speak for itself, to be the focus and point rather than concerning myself with creating a public persona and building an audience based on how interesting or charismatic I am as an individual. To me, the writing is the writing is the writing. I don’t mind talking about myself or discussing the whys of my creative interests and choices, but I want my writing to speak first. In fiction, having a cult of personality around the writer seems like a distraction.

[GdM] Portland is a city with a very distinct feel: rainy, green, eclectic, and a little weird in the best way. As a longtime former Portland resident myself, I’m curious: did Portland seep into your writing at all?

[SLY] I’m sure it did. I didn’t have a car and live in an old brick building with ancient radiators and no AC, which results in experiencing the weather and seasons very intimately. Particularly since I started writing when I had a baby and toddler and they needed to go outside, rain or shine, 365 days of the year. My partner has joked that I’m a houseplant because I’m so seasonally affected. Once I get cold, I stay cold, and that more than anything tends to creep into my writing; the temperature a character experiences in relation to another person is often the first indicator about how they feel towards that person, or how their feelings are beginning to change.

I also grew up out in the Willamette Valley area, out in the country, and I spent a lot of time in the woods as a kid. I used to forage and learned to identify plants (and nearly poisoned myself a few times), which was an experience I drew from when crafting Helena’s character. The environment is such an intrinsic piece of gothic literature often acting as a reflection of the characters. Since the story environment in Alchemised is predominantly either intensely claustrophobic or utilizes rather oppressive architectural psychology, giving Helena a place to go where she isn’t walled-in was one of the few occasions where she’s in a more natural state, instead of environments that she’s entrapped or constrained by.

[GdM] Do you still write on your phone, chasing the story as it comes, or have you shifted to a more mapped-out approach?

[SLY] I don’t write on my phone much anymore. When I was writing serially, being more of a pantser than a plotter, using my phone worked really well. Now I’m more plot and research-oriented in my writing development. When revising full manuscripts, having a bigger screen and an actual keyboard has become imperative.

It’s taken me a while to figure out what really drives me as a writer, because at first my projects were fairly varied in topic, genre, plot. It seemed mostly random what got finished, what I felt really inspired and impassioned to work on. Now as I keep refining my process, I’ve realized that my writing always starts with a question, something that doesn’t have an easy answer for. The writing process is often my way of working through the various pieces of that question.

With Alchemised, the question was morality in war, exploring all the ethical greyness that tends to be swept aside to create a cleaner good vs evil narrative in real world reporting, literature, and other media. The initial question I wrestled with was the ethical trolley problem that spies represent; the question of what’s an acceptable loss or atrocity to maintain a cover?

That was where I started. But then in the process of delving into the brutality of war without all the gilding and lionizing of traditional heroism, the premise evolved into questioning how societies make heroes. When you start poking at that, you start seeing which nuances get erased by flattening the narrative into a neat dichotomy and realise that countless people have to disappear for the heroes to be shaped into these near-mythic figures.

[GdM] In Alchemised , you explore one of humanity’s oldest obsessions: the fear of death and the desire for immortality. What drew you to build the story around that tension?

[SLY] Funnily enough, I think it’s because immortality has always seemed horrifying to me. The thought of being unable to die, no matter what’s happening, that you’d always be alive, forever, sounds utterly nightmarish. I think that fear originated in a dread of the afterlife that I developed growing up; the way it was presented to me was choice between eternal, inescapable boredom or eternal inescapable torture, and I thought both options sounded awful.

Because of that, it’s always been morbidly fascinating to me how idealised immortality tends to be. In Alchemised, I was able to explore that in both the literal and the figurative sense because of the dichotomy between the Undying and the Eternal Flame. The High Necromancer has defeated death, and made his followers immortal, so that neither he nor they need to fear death, while the Eternal Flame is devoted to preserving and perpetuating legacy and memory of the Holdfasts because of the promise of an eternal afterlife. It’s a reoccurring element of the story that individuals, groups, even countries proactively define themselves in contrast to or opposition of others, but later, when the surface is peeled back, there are fundamental similarities that are just being manifested differently. They’re almost never the antithesis they claim to be, they’re mirrors.

The initial idea about necromancy/reanimation came from a conversation with a friend about organ donation. This person is generally pretty laid back and not particularly spiritual or religious, but she had this absolute disgust to the idea of organ donation, of any part of her body being taken or used once she was dead. I found this surprising because to me, once I’m dead, I don’t care what happens to my body. But she had such a visceral reaction that it wasn’t really a topic where an objective conversation was possible. It was too personal and emotional, which was just the kind of emotional/ethical conflict that Alchemised needed. Necromancy is such a slippery slope; whether you decide the dead are an acceptable resource to exploit, or that it’s better to sacrifice the living. Either choice has the potential for abuse or terrible ramifications. When writing Alchemised, I wasn’t interested in readers agreeing with the characters’ choices because it’s intended to be another trolley problem. I wanted to show there’s a cost to choosing one way or the other, and there’s also a cost for refusing to choose. The lack of a perfect, moral solution is the point.

The concept for the Undying started with reading the Russian folklore about Koshchei the Deathless, but I wanted to expand it into something that fit into the framework of scientific alchemy. The worldbuilding of Alchemised is something that I jokingly refer to as ‘science-fantasy’ because alchemy tradition itself is so deeply rooted in trying to reconcile the religious and the scientific, filling gaps or inconsistencies with mythology, and deferring to religion when there’s a conflict. In Alchemised, there’s a similar approach by the characters, in which they are trying to understand their world scientifically but it’s always channelled through the mystic lens of their faith.

[GdM] Can you tell me a bit about your main characters? How do they interact with the setting and worldbuilding, which feels like a character in its own right?

[SLY] The characters in many ways sprang up from their philosophical perspectives. Helena leans existential; she’s an outsider, and that makes her very observant. She also sees the world through a different lens than those around her because she didn’t grow up with the same assumptions that they did. She notices the inconsistencies that others are raised to overlook. However, she wants to belong, so she tries to reconcile them and absorb the dissonance until she can’t anymore. Once she reaches the point of disillusionment, she ultimately chooses to create meaning for herself through her choices, rather than deciding that it’s all meaningless and giving up.

From the very first line of the book, her vision is crucial to her. She’s always searching for the light, looking towards horizons, but there’s barriers; stasis, the walls of Spirefell, the skyscrapers of Paladia, the mountains. She doesn’t realise that she is a light herself, but that’s why she survives because she’s never passive in her ‘captivity.’ When cornered, she creates and transforms.

A critical part of that process is by becoming self-reflective, rather than defining herself by what people tell her she is. Initially she unquestioningly accepts the ways people criticize and define her because she thinks if she shrinks and suppresses herself enough that she’ll be able to fit in and find belonging, and it’s only when she stops believing that, that she evolves further.

I really wanted Helena to break archetypes, and so she’s constantly turning out to be something different from what she appears to be. A classic gothic heroine in red, but in a way also the mad wife and the ghost. A healer, but not because she’s just so tenderhearted and pure (both qualities associated with femininity), but because she’s calculating, and rational enough to choose a role that she knows she’ll be derided for because she can comprehend how vital and undervalued it is. I’ve always thought traditional ideas of femininity underestimate and disregard how deeply pragmatic the actual actions of care are.

Over the course of the war, she moves through the four classic alchemical stages of transmutation which have four colours associated with them: black, white, yellow, and red. Red is the final stage. Making Helena’s colour motif red had this dual purpose of not only invoking the traditional gothic heroine in red (vs the ingénue heroines in white) but also symbolically reflecting the transformation she’s undergone over the course of the story. She is exceptional not only because of her capacity to evolve to meet the circumstances she’s dealt, but because what she becomes is someone who creates meaning for herself by choosing to care in an uncaring world and do what good she can. On a symbolic level, she is the pinnacle of the spiritual alchemical transformation because she reaches the point where she doesn’t need an ideology or an external narrative about the universe to give her purpose–she makes it for herself.

Kaine, on the other hand, becomes a nihilist in his grief and isolation. When he’s disillusioned, his response is to believe in nothing anymore, to view life and everything else as pointless. He believes he’s already in hell, in the abyss, and his way of coping with that is pursuing personal vengeance without caring about the cost. He doesn’t regard the future as real, or connected to him, and so he acts without much impunity. He begins in the first stage of alchemy, the blackening, literally reaching a point of putrefying and decomposing, but then enters the second stage, leucosis or purification. However, because of the way he sees the world, he doesn’t progress beyond that, he stays there and becomes this very stark and distilled person who needs an external light by which to orient himself and begin to perceive the future as something that he’s actually a part of.

In the first and second parts of the story, I treated the house and the war as if they were characters themselves. It was important to me that neither existed merely as a backdrop for the story, but felt as overpoweringly real to readers as they did to the characters.

The house especially is all things gothic, and when I was crafting it, I wanted it layered with symbolism, in shape, in the materials, in the religious meaning of the spires being utilized by the Ferrons to invoke their own family crest. The house is supposed to represent all this past hubris and aspiration, but all that’s left is this half-dead entity, a corroding dream. I read Shirley Jackson and several Victorian thrillers for inspiration because I wanted there to be layers of haunting in the first part of the book. There’s the actual dead, but there’s also numerous metaphorical ghosts, memories and grief, the house is drenched them.

Similarly, in writing the war, I wanted to write it as a character because I wanted to be brutal with its reality. I get frustrated with stories that treat war like it’s just a stage to create a high-stakes epic, something aspirational to self-insert into. I wanted the destruction to be felt because the characters’ actions are not intended to be viewed as right or wrong; what they do in the story is driven by unspeakable circumstances, and it was important to capture the sense of duress that prompted them. The character’s choices aren’t going to make sense if you don’t fear the alternatives as much as they do. While there are a number of horrific characters in the book, in my mind the war itself was the worst one.

[image error]Author SenLinYu Image by Katy Weaver Photography[GdM] The setting in Alchemised feels just as alive, haunted, and full of menace as the characters themselves. How did you approach crafting the atmosphere? Were you consciously drawing on gothic storytelling traditions when you crafted the world?

[SLY] One of the things I enjoy most in early drafting is determining how much distortion I want to add to the point of view. I never consider my narrators reliable; there is always a gap between the ‘objective truth’ in the story and what the POV character interprets. When I’m writing, I’m constantly considering the story through both lenses as I evaluate how to depict things, what’s going to appear but be overlooked, what’s going to be misinterpreted, etc.

I was already familiar with gothic storytelling tradition when I began writing, but while revising, I studied the feminine gothic tradition specifically. Atmosphere is such a crucial component of gothic stories and I wanted the environment to mirror Helena’s interiority, both in keeping with the genre, and because it reflected her psychological state, that all she noticed around her was danger.

I try to utilize the art technique from sumi-e painting in my writing. It is the use of negative space, or expressive reticence. The idea being that rather than rendering every detail explicitly, the artist holds back and uses the power of suggestion to evoke the reader’s mind and make it fill in what isn’t there, which causes them to actively engage with the text rather than having everything handed to them and allowing them to passively read. It’s something I specifically try to utilize for creating atmosphere and in describing sensation or emotion.

There are several authors who have observed that over the last fifty years we increasingly associate ‘storytelling’ with visual mediums like TV and film, rather than thinking of it as written or auditory, and that as a result books sometimes read like written films rather than leaning into the aspects of storytelling exclusive to the literary medium. I try to focus specifically on capturing elements of story that don’t translate to film, such as literature’s capacity to make you feel with the characters.

Even though the story isn’t in first person, the narration stays very grounded in Helena’s point of view so that the reader experiences the events with her and can understand why she makes the desperate choices that she does.

[GdM] Do you set any boundaries for your characters’ moral choices, or is part of the appeal testing how far they can go? Were there lines that you were not willing to cross?

[SLY] I didn’t specifically set boundaries for myself in writing and depicting the wartime darkness; for me the question always is how to depict the reality of war. I think that culturally, we do ourselves a profound disservice by making war a palatable source of entertainment in choosing to primarily depict it as a profitable, aspirational spectacle because that makes for a great story.

Because of that, it wasn’t a moral line that I drew for the characters so much as a constant evaluation of their circumstances and their mental states in deciding how far they were going to go. Fictional morality is quite different than real world morality. Murder in fiction is relatively common and something the audience will often root for, whereas kicking a dog is seen as beyond the pale and a character that does it becomes such an unforgivable monster that people won’t even want to read about them. So the question was finding which moral line wasn’t kicking a dog but went far enough that readers would never be comfortable with it, even if they could understand why it happened.

[GdM] Do you have more fun redeeming your characters—or breaking them?

[SLY] I never really thought about the story as being about redemption. I’ve always been frustrated with stories where a character is committing all kids of unspeakable acts but then in the climax dies in a blaze of glory, which moves them into the ‘redeemed’ category for the epilogue and everyone sort of ignores all the harm because there’s no speaking ill of the dead. The redemption in death trope has always felt like a cop-out to me.

I’m not a very forgiving person and I don’t think dying precludes someone from criticism, and I also don’t think it’s the pinnacle of heroism. When I was plotting Alchemised, one of the questions I was pondering a lot was ‘what if the ‘irredeemable’ character doesn’t conveniently die at the end? What do you do with them then?’

[GdM] One of the things that struck me most about Alchemised is how ruthless the characters are—pitiless in refusing to soften its edges. However, the story also allows for moments of quiet. How do you strike that balance, letting a moment shine or be reflective without blunting the ruthlessness that drives the story?

[SLY] It was one of the earliest conversations I had with my editor, actually. There was a discussion early on about whether Alchemised should be published as a trilogy or a standalone. The length leaned towards trilogy, but the unconventional structure and journey were more suited to a standalone, which is what we chose to prioritize. However, I was very insistent that as a standalone the book needed to be long because I didn’t want it reduced to nonstop action. It was vital to me that the story be allowed to breathe, for the characters to pause. Grief is such an important part of the story, and it’s an emotion you have to sit with to feel.

[GdM] Those quiet moments often hit harder precisely because of the brutality around them. Do you see them as a way to ground the reader emotionally, or as a fleeting chance for the characters to reveal their humanity and pause?

[SLY] Both, really. I think it’s easy to get lost in the rush and immediacy of a story if it’s careening at breakneck speed all the way to the end. I have an intense suspicion of how utilitarian everything, including storytelling, has become in the last decade or so, where it’s all about soundbites and anything that doesn’t serve the narrative—or perform a vital role—has to be gutted. When stories are reduced to their mechanics and function like that, it sucks the soul of them and rips away the artistry of storytelling.

I didn’t want Alchemised to be a rollercoaster ride where you’re locked in place and you don’t have any choice but to stay through every drop until you reach the end. It’s supposed to be an intentional journey even though it is harrowing. I feel like we’re so accustomed to the blandness of mass appeal, of reducing symbolism to aesthetics, and consuming things in this passive, algorithmically frictionless way nowadays that it can be shocking to experience something that requires effort and chooses to be uncomfortable. But as a reader, as a thinker, those are the kinds of books and media that I personally find meaningful, that I reread and remember, because they force me to reflect, to reevaluate my views, or begin to see things differently. That’s what I’m interested in writing. But you can’t speedrun reflection, the story has to pause to breathe and ground itself.

[GdM] Trauma is prevalent in your work; it shapes voice, choices, and relationships. How do you approach writing trauma in a way that feels authentic?

[SLY] I tend to develop my characters based on their psychology. Once I have an idea of who I want them to be in the story, the first question I ask is what is it about their life that has made them this way? What experiences colour how they understand and interpret the world? I think that trauma unfortunately shapes people’s actions and reactions in very fundamental ways that follow them throughout their lives.

In Helena’s case, she has displacement trauma. She desperately wants to have a secure sense of belonging, and it makes her incapable of letting go or giving up on anyone. She holds onto other people as tightly as she wants them to hold on to her. In other circumstances, she might have reached a point where she was less affected by it, but because of the war, because of the political tension created by her admission to the institute, it’s something that’s intentionally weaponized and exploited by others until she’s consumed by it, and that’s a driving force in her absolute refusal to give up on people.

[GdM] What is next for you after Alchemised ?

[SLY] I’m working on my next book. It’s still in early stages. As I mentioned above, my story ideas usually come to me either as a question or a feeling that I’m struggling to unravel in myself, and writing is my way of processing it. So, I have my question I know the story I want, and have the central characters sketched out, but I feel like I don’t have a sufficiently broad perspective to capture the nuances that I’m interested in wrestling with. There’s also a particular ambience that I want to create for it that’s different from what I’ve done before, so I’m still in reading and researching mode.

Read Alchemised by SenLinYuThis interview with SenLinYu was first published in Grimdark Magazine Issue #44

The post INTERVIEW: with author SenLinYu appeared first on Grimdark Magazine.