Another Feather In Your Cap

The practice of killing birds for their plumage was unsustainable and, for some, repulsive. Speaking in the House of Lords on May 19, 1908, Lord Avery opined that “it is evident that unless the slaughter is stopped, several species of birds will be in a few years be absolutely exterminated…it is not only the fact that several species will be utterly annihilated, but the victims are just he most beautiful; in fact, their beauty is their ruin. Moreover, birds’ feathers in hats are, I submit, not ornamental but, in the circumstances, repulsive”.

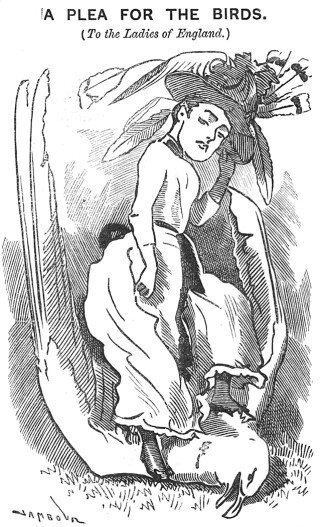

Lord Avery’s views were shared by Emily Williamson and her supporters who had, in 1889, founded the Society for the Protection of Birds, specifically to oppose the practice of using birds’ feathers for what they termed “murderous millinery”. Their campaigning eventually bore fruit with the passing of the Wild Birds Protection Act in 1908 and the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act of 1921, the latter prohibiting the importation of certain types of feather.

Commercially, too, the practice of killing birds for their feathers was unsustainable, driving up prices as the providers of the plumage were driven ever closer to extinction. As ostriches were large, flightless birds, could they perhaps be domesticated, providing a plentiful supply of feathers through selective plucking in a way that left them unharmed and free to enjoy a happy and contented life, some mused?

The first serious attempts to farm ostriches for their plumage began in South Africa around 1865 with just eighty domesticated birds. By 1875 the number had increased to 32,000 and 154,000 in 1891 providing the vast majority of the 212,000 lbs of feathers the country was exporting at the time. South African farmers were reporting returns of 5000% on their initial investment in the birds.

Techniques improved. Anthony Trollope, writing in Illustrated London News in 1878, brought his readers news of a new South African process of sustainable feather harvesting. The bird was not denuded of feathers all at once but were selectively clipped near the body in small batches every seven months. The dry and shrivelled quill was then removed at a later date to minimise the bird’s discomfort.

Recognising the similarities between the climate of the South and West of the United States and the habitats enjoyed by wild ostriches and attracted by the profits made by South African farmers, it was not long before attempts were made to farm ostriches in America. However, it was not plain sailing.

Under the care of a South African ostrich farmer, Dr Charles Sketchley, a herd of two hundred ostriches were despatched from Cape Town via Buenos Aires to New York in 1882. By the time they had arrived in the Big Apple, 90% had died and after transportation to Anaheim by rail the survivors were so unwell that plucking had to be delayed.

E J Johnson, founder of the American Ostrich Company, had more success, not losing any of the twenty-three birds he brought over to New Orleans and then on to Fallbrook in California where they flourished over several decades. Ostrich farms gradually became established in America, offering a supply of feathers as well as tourist attractions with visitors offered the opportunity to ride on an ostrich or sit in a carriage drawn by one.

However, following the Wall Street Crash and the general economic downturn in the 1930s, the global appetite for feathers declined, becoming a niche luxury item, as they are today. With the rise in environmental awareness, there are also ethical concerns about live-plucking of ostrich feathers and, indeed, whether they should be domesticated at all.

The days of the ostentatious ostrich feather seem to be well behind us.