On Progress and Regression

Each month, we comb through dozens of soon-to-be-published books, for ideas and good writing for the Review’s site. Often we’re struck by particular paragraphs or sentences from the galleys that stack up on our desks and spill over onto our shelves. We sometimes share them with each other on Slack, and we thought, for a change, that we might share them with you. Here are some we found this month.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor, and Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

From Nora Claire Miller’s Groceries (Fonograf Editions), a book-length poem:

I hand ▯s to the teller, imperfect amount after imperfect amount. ▯s aren’t money but they can come close. shapes, we call them, because there is no living thing with which a ▯ lines up. we call something good when we don’t feel like performing a comparison. we call something lit up when its conceit cannot be described. we call something impractical when it has a meaning we are not involved in. we call something dumbfounding when it is floating in thin air.

From Lance Richardson’s biography True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen (Pantheon):

Peter had started seeing a woman in Reno named Lisa Barclay Bigelow, a great beauty (she would model on the covers of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar) who’d been in Nevada to secure a divorce of her own. Lisa lived in New York, and on November 19, Peter took her and his two children to the Coney Island aquarium, which had recently installed an Amazon River scene complete with piranhas and live tropical birds. Along the way, they all stopped at Pier B in Red Hook to examine the MV Venimos, which would soon ferry Peter to the genuine Amazon. “I don’t think I’ve ever been around the world,” Luke said after hearing the plan. Peter pointed out that his seven-year-old son was nevertheless a world traveler of sorts, having sailed from Italy on the Andrea Doria, which was now at the bottom of the Atlantic after sinking near Nantucket in 1956. Sara Carey, aged five, listened to this shocking news, then warned her father that he, too, would end up at the bottom of the ocean if he tried to go around the world, and sharks have “very sharp teeth.” She did not believe he was really leaving on the MV Venimos. He could barely believe it himself, though he showed no sign of trepidation. The next day at the pier, he said goodbye to Bill Styron, who’d come to bid him bon voyage. Styron was struck by his friend’s equanimity: “his spectacles planted with scholarly precision on his long angular face, he might have been going no farther than Staten Island, so composed did he seem, rather than to uttermost jungle fastnesses where God knows what beast and dark happening would imperil his hide.”

From Claire-Louise Bennett’s novel Big Kiss, Bye-Bye (Riverhead):

On the last night in the old place it crossed my mind to write a few lines, but I was too tired and read most of a long film review before turning out the lamp for the last time in that particular room. It occurred to me anyway that I would most likely end up saying trite things along the lines of a chapter of my life is coming to an end and the next phase will surely be the ultimate phase, full of adventure and glory and ease of mind at last, etcetera, etcetera. It’s surprisingly difficult not to succumb to that kind of vapid drivel when one is on the brink of shifting into a new and unclear situation. On such a threshold one is susceptible to feeling and expressing hopes for the future, which begins tomorrow, a bright new start, where I will do things differently, with greater integrity and resolve, and so on. I reached down and turned out the lamp.

From the political philosopher Rahel Jaeggi’s Progress and Regression, translated from the German by Robert Savage (Harvard University Press):

Progress, we are used to saying, is a change for the better, meaning that regression would be a change for the worse. While in a sense this is true, it is not entirely accurate. What is crucial, and what I will be arguing in this book, is that progress refers to a form of change, or more precisely, a certain way of responding to crises and solving problems. In brief, progress is a self-enriching experiential learning process for finding solutions to problems that are systemically blocked under conditions of regression.

Progress, as I will conceptualize it throughout this study, has nothing to do with a smugly self-congratulatory Whig history of Western imperialist societies. Nor is regression the paternalistic verdict on those deemed to have been left behind by Western modernity. Rather, the progress/regression binary is primarily the conceptual vehicle for critique and self-critique of the very societies that pride themselves on their supposed progressiveness.

From Vernon Lee’s preface to his collection of ghost stories, (Unnamed Press), first published in 1890:

That is the thing—the Past, the more or less remote Past, of which the prose is clean obliterated by distance—that is the place to get our ghosts from. Indeed we live ourselves, we educated folk of modern times, on the borderland of the Past, in houses looking down on its troubadours’ orchards and Greek folks’ pillared courtyards; and a legion of ghosts, very vague and changeful, are perpetually to and fro, fetching and carrying for us between it and the Present.

From The Lord (NYRB Classics), a novel by Anglophone Palestinian writer Soraya Antonius, originally published in 1986, in which an English missionary recounts a story to the narrator, a journalist:

“I felt a horror of her, of the scene, something between us like a wall. No, a sheet of gelatine like those the grocer sells, that’s it, something brittle and sharp but transparent through which we each distorted the other.”

Helpfully illustrating the sort of sound a sheet of gelatine might make if it were to be crumbled by a giant jelly-maker, the recorder switched off at the end of the spool.

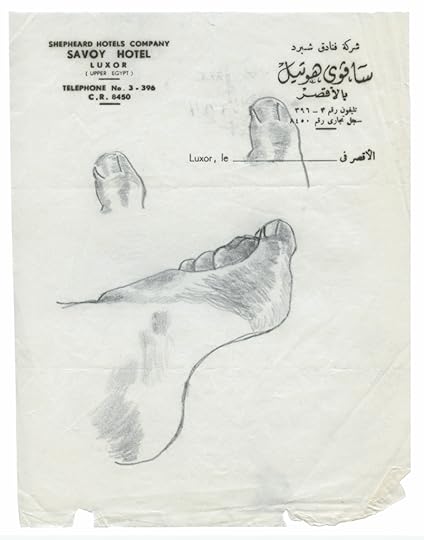

A drawing by Paul Thek in Stay away from nothing (Primary Information), a collection of letters from Thek to Peter Hujar accompanied by Hujar’s photographs:

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers