How to (not) write about numbers

Image by Andy Maguire | CC BY 2.0

Image by Andy Maguire | CC BY 2.0If you’ve been working on a story involving data, the temptation can be to throw all the figures you’ve found into the resulting report — but the same rules of good writing apply to numbers too. Here are some tips to make sure you’re putting the story first.

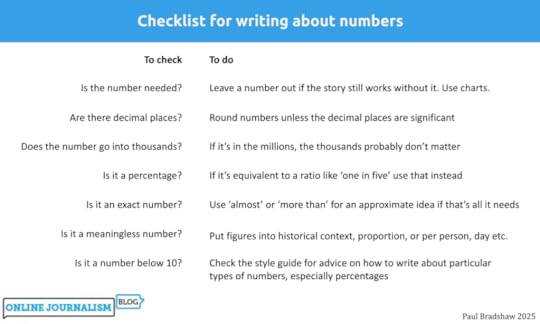

Rule 1: Don’t write about numbersThe first rule of writing about numbers is not to write about numbers — if you can help it.

As a general principle, just as you should never include an unnecessary word in a piece of journalism, if you can leave a number out of a story and the story will still work, you should probably leave that number out.

This can be difficult if you’ve invested a lot of time and effort in getting to those numbers — but even those numbers are only a means to an end. They might lead you to case studies, or give you the questions to ask of those in power. Your story therefore might focus more on those.

Where you do mention numbers in the story, less is more: readers will only be able to take in so many numbers, so try not to use more than one or two numbers in each paragraph (start a new one if you have to), and make an editorial decision about which numbers are most important, and which ones can be cut.

If you have a lot of numbers you want to include, you can always put them in a chart, map or table, for readers to explore if they wish.

It is also important to remember that numbers represent people, whether directly (the number of people affected) or indirectly (an amount of money that could be spent on helping people), so try to keep people at the heart of the story, and not the numbers that represent them.

Rule 2: Don’t write about decimal places (unless they are significant)

Rule 2: Don’t write about decimal places (unless they are significant)In most situations decimal places aren’t important, so only use them if they matter.

When do decimal places matter? If the difference between two figures only exists at that level, or if decimal places represent a meaningful change (between small numbers, for example).

So, in the sentence “42.5% of their goals have been scored via set-pieces” there is no reason for the reader to do extra mental work processing that half a per cent — the textual equivalent of having 3D on a pie chart. “43%” is just as meaningful and much clearer.

Only in a sentence like “3.5% of children, up from 3.2% last year” are the decimal places important enough to be included, firstly because it is at that level that differences exist but also because rounding the numbers (to 4% and 3%) would risk misrepresenting the scale of the change.

If you do include decimals, be consistent: if one figure was exactly three in the example above you’d write “3.5% of children, up from 3.0% last year” to make it as easy as possible to compare the two figures.

Rule 3: Don’t write about the hundreds and thousandsEqually, if your number is in the millions, don’t sweat the small stuff.

A sentence like “Schools spending £5m on agency staff” communicates the scale of an issue cleanly and succinctly. “Schools spending £5,325,000 on agency staff” might provide more detail, but it doesn’t change the story: in both cases you are really trying to say ‘a lot of money’, and the first option is more efficient at doing that.

The same principle applies when talking about figures in the hundreds or tens of thousands: “Hospitals making £528,000 per year from parking fines” is just as effective as “Hospitals making £528,320“.

As with decimals, if the story is about differences that are only seen in the more detailed numbers, then the small stuff does become meaningful enough to include. “School agency staff spend has risen from £5.1m to £5.3m“, for example (which could also be written as “School agency spend rises by £200,000“).

You could probably sum up the two above rules another way: don’t use seven figures when one will do.

Rule 4: Don’t write about percentages (write about ratios)

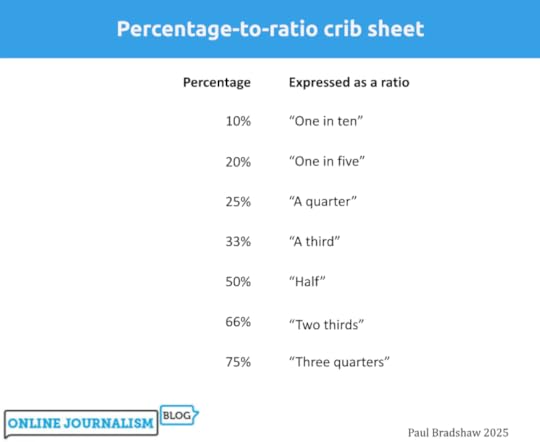

If your figure happens to be a nice round 20%, then congratulations! You don’t have to write that number. Instead, you can write a ratio. So, a sentence like “police arrested 20% of those that they stopped” can be better written as “police arrested one in five people that they stopped“.

Ratios are easier to understand because they get straight to what a number means in practice, rather than the reader having to work that out.

For example, “50%” really just means “half”, but we understand the latter more quickly. “Half of pupils entitled to free school meals” allows us to remove the number from “50% of pupils entitled to free school meals“, and present that information in the type of language people would normally use.

You can use a ratio calculator to find out what ratio a percentage can be expressed as.

If your percentage relates to change, remember that an increase of 100% basically means something has “doubled” and an increase of 200% would be “tripled”.

Be careful, however: if you are comparing different numbers don’t compare a ratio with a percentage. A phrase like “Dropped from 65% to half” requires the audience to do more work than they should. Keep both numbers as ratios if you can, but if you can’t (only some percentages can be expressed as meaningful ratios), it is better to express both as percentages.

Rule 5: Don’t write about exact numbers These stories lead on ‘almost’ or ‘more than’ round figures, rather than bogging the story down in irrelevant detail

These stories lead on ‘almost’ or ‘more than’ round figures, rather than bogging the story down in irrelevant detailAnother way of reducing the digits you are using is to add an ‘almost’ or ‘over’ into your description where percentages are close to a particular ratio or round figure.

So, for example, the sentence “49% of pupils entitled to free school meals” could be rewritten more clearly as “Almost half of pupils entitled to free school meals“. And the sentence “Police arrested 21% of those stopped” rewritten as “Police arrested more than one in five of the people that they stopped“.

Equally, “Schools spending £5,325,000 on agency staff” can be rewritten as “Schools spending over £5m on agency staff“, and “Hospitals making £395,000 per year from parking fines” might be more simply expressed as “Hospitals making almost £400,000 per year“.

As always, only do this where the exact numbers are not significant. An election poll that puts one party on 47%, for example, would not be reported as “almost half” because it is likely that figures were only slightly different before, making small changes significant.

Rule 6: Don’t write about meaningless numbersWherever possible, try to make numbers meaningful. Large numbers out of context can not only be boring, they can also be dehumanising and misleading.

For example the sentence “Schools spending more than £5m on agency staff” doesn’t make it clear whether that is a large amount. There are a range of ways we can make that number more meaningful:

Historical context: is that number larger or smaller than in previous years? Is it better to report the change than the scale? “Schools agency staff spend up from £5.1m to £5.3m” would be an example of that.Per person: if you know, or can find out, the overall population involved (that might be employees, patients, or service users) then consider dividing the total by that to make it more meaningful. For example: “Schools spending over £6,000 per pupil on agency staff” As a proportion of the budget/population: what sounds like a large amount often isn’t quite so large as it seems, when put into the context of the bigger picture — or it might sound like just another number without context. An example of this context would be: “Schools spending a quarter of budget on temporary staff” or “Parking fines make up less than 1% of hospital income“.What would it pay for: your story might be telling us what is being spent on something, but why does that matter? Typically, it matters because it could be spent on something else, so many stories will focus on that: “Agency staff spend would pay for a new teacher for every school“, for example, or “Schools spending more on agency staff than special educational needs“.Smaller timescale: what is that figure per day, week or month? Often a smaller but more imaginable figure can have a greater impact, e.g. “Schools spending £96,000 per week on agency staff”These techniques can be combined, too: for example comparing historical amounts per person.

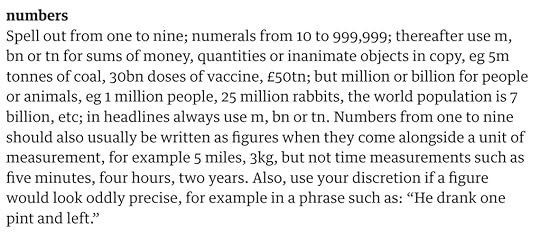

Rule 7: Don’t write numbers when the style guide says to use words The Guardian Style Guide section on numbers

The Guardian Style Guide section on numbersMost news organisation style guides specify that numbers below 10 should be written as words (i.e. “seven”, “eight”) with digits used from 10 upwards.

But there are often exceptions to this. The BBC, for example, uses digits below 10 in headlines, and BuzzFeed does so for listicle headlines and video captions. Where numbers are written in succession, their style guide advises consistency:

“e.g. “9, 10, and 11,” NOT “nine, 10, and 11”; the same applies to ranges of numbers, e.g., “We are expecting eight to ten people” or “We are expecting 8 to 10 people” (both OK!).“

Numbers below 10 are just one element of style to consider. What about ordinal numbers like “seventh”? What about percentage signs versus the word “percent” — or is it “per cent”? (In the UK it’s two words) Do you spell out “million” or just use the letter m? Are you writing about percentages or percentage points?

These are all questions a good style guide should answer.

The Guardian’s entry for ‘numbers‘ provides a useful list of potential considerations:

Spell out from one to nine; numerals from 10 to 999,999; thereafter use m, bn or tn for sums of money, quantities or inanimate objects in copy, eg 5m tonnes of coal, 30bn doses of vaccine, £50tn; but million or billion for people or animals, eg 1 million people, 25 million rabbits, the world population is 7 billion, etc; in headlines always use m, bn or tn. Numbers from one to nine should also usually be written as figures when they come alongside a unit of measurement, for example 5 miles, 3kg, but not time measurements such as five minutes, four hours, two years. Also, use your discretion if a figure would look oddly precise, for example in a phrase such as: “He drank one pint and left.”

BuzzFeed, the BBC, the Bristol Cable, Canadian Press Stylebook and the Australian Broadcasting Company are just some of the organisations that advise never to start a sentence with a numeral (unless it is a year). And there’s no apostrophe when talking about a decade like the 1960s.

When it comes to percentages the use of the word ‘per cent’ (British English) or ‘percent’ (US English) has changed over the years, with more style guides (including AP) advising using the percentage symbol, but not all.

Changes between percentages should be described as “percentage points” increases, “Any sentence saying “such and such rose or fell by X%” should be considered and checked carefully“, The Guardian notes.