CMP#228 Two children's books, one plot

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Click here for the first post in the series. CMP#228 Two books for children, one plot

Clutching My Pearls is my ongoing blog series about my take on Jane Austen’s beliefs and ideas, as based on her novels. Folks today who love Jane Austen are eager to find ways to acquit her of being a woman of the long 18th century. Click here for the first post in the series. CMP#228 Two books for children, one plot

Meeting the governess I recently received a digital copy of a rare and obscure children’s book by

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM), generously supplied to me by the University of Iowa. Now that I have a copy of The West Indian, I think I have succeeded in tracking down all of EKM’s books, so I can put together a definitive list of attributions and clear up some mistaken attributions.

Meeting the governess I recently received a digital copy of a rare and obscure children’s book by

Eliza Kirkham Mathews

(EKM), generously supplied to me by the University of Iowa. Now that I have a copy of The West Indian, I think I have succeeded in tracking down all of EKM’s books, so I can put together a definitive list of attributions and clear up some mistaken attributions.The West Indian was published in 1821 in Derby and attributed to “Mrs. C. Mathews,” 19 years after EKM's death. The most logical explanation for the appearance of this title after EKM's death in 1802 is that her husband Charles sought out publishers for the manuscripts Eliza left behind--even though he and his second wife had no great opinion of her writing abilities. The second Mrs. Mathews was also an author who compiled and wrote her husband's memoir after his death. Her effusive, breezy style is very different from EKM's. Anne Jackson Mathews said of her predecessor: “She knew nothing of society or of the world. Her reading had been slender, and confined to the generally mawkish style of the novels of that day. From them she gave faint impressions of nature; and no publisher thought them worth much more than the cost of printing. Disappointment followed disappointment.”

I like to think Charles Mathews worked to find publishers for EKM’s manuscripts out of affection and respect for her, knowing that it would have been something that she wanted. An early composition?

The West Indian appears to be an earlier draft of Ellinor, or the Young Governess which was published in 1802). In both stories, young Ellinor Montague is orphaned and needs to support her little sister Sophy. Just like the other children’s books I have reviewed here, both tales contain educational discourses on morality, history, botany and so forth, held together with a narrative in which the governess awakens the children’s love for learning and improves their characters. Although both books follow this formula and have the same basic premise, the details are different. In The Young West Indian, the Somerville children learn about castles and Stonehenge and ants. In Ellinor, the Selby children learn about ducks and the sources of rivers.

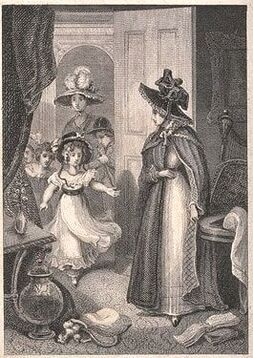

Ellinor is written with third-person narration in a more highly wrought sentimental style, while The Young West Indian, written in epistolary style, has more of Georgian restraint and periodicity about it. I think it must be an earlier, as opposed to a later, composition. Here Ellinor describes her introduction to her pupils in a letter to her sister: “My dear children,” said Mrs. Somerville, leading me into the room in which [the] Miss Somervilles and Miss Mountford were amusing themselves, “this is the young lady who has kindly undertaken the cultivation of your minds; pay to her that deference and respect which she so highly deserves; treasure her instructions, for they will lead you to virtue, and ultimately to happiness: be attentive to her admonitions, obedient to her commands, and submissive to those punishments, which for your advantage, she may sometimes think it proper to inflict.”

Untangling Misattributions

Untangling MisattributionsI was convinced that EKM is the author of Ellinor, or the Young Governess because it includes a poetic tribute to her deceased cousins, which also appeared in her posthumous book of poetry. As well, of course, Ellinor’s desperate situation and fall from gentility after the death of her parents, parallels EKM’s own life. EKM did not use her own poetry in The Young West Indian. Instead, the children recite poems by Parnell and Thomson. But she does describe Kent’s Hole, a cavern on the coast of her native Devonshire.

Miss Mountford, a ward of the Somerville family, is the spoiled West Indian of the title. As Mrs. Somervile explains to Ellinor: “'Poor child! Early deprived of her mother, she has been left to pursue her own silly inclinations, till this blameable indulgence has destroyed the equanimity of her disposition, and rendered her haughty, impetuous, and almost uncontrollable.’ I have been introduced to my pupils, and find them as Mrs. Somerville described. Miss Mountford, the West-Indian, is indeed… very naughty and very impetuous.”

Miss Mountford treats her servant, a pidgin-speaking black girl, with cruelty.

“Do as I command you, instantly, or I’ll murder you!”

“Den me go to great good Being, Missy; but if me tell lie me not able to pray to him.”

“Dost think, you black ugly wretch,” replied Miss Mountford, “you’ll ever go to heaven? Look, how white my skin is compared to yours!”

“Ah, Missy, but me white heart, and dat’s better den white skin!”

“’Insolent creature, take that, and that,’ striking her as she spoke, with the utmost violence…

I entered the room [and] caught her arm and prevented this unjust action….

"‘She is only a negro,’ returned Miss Mountford, ‘and negroes one may be allowed to beat.”

“And why? [Ellinor challenges her] Are they not equally alive to feeling with yourself?...The same Power who created you created them; like you they are formed, and like you have an immortal soul: in what then do they differ? In the colour of their skin?”

Ellinor writes to her sister: “How poor, contemptible and mean appears the immensely rich Miss Mountford, when compared with the honest and ingenuous Zelia; while we turn with disgust from this rich and powerful West-Indian, we involuntarily pay the homage of admiration to a poor negro, the innocent and unsophisticated daughter of Nature!

Fortunately, thanks to Ellinor’s tutelage, Miss Mountford (we never discover her first name) repents and reforms, especially after she experiences the pleasure of bestowing charity upon some unfortunate poor village girls. As well, Ellinor’s pupils learn to despise the empty pomp and vanity of the fashionable world after visiting with the snobbish Miss Harrington. The story ends rather abruptly and we are given no information about what happens to the Miss Somervilles or Miss Mountford or with Ellinor and her sister in the future.

Fortunately, thanks to Ellinor’s tutelage, Miss Mountford (we never discover her first name) repents and reforms, especially after she experiences the pleasure of bestowing charity upon some unfortunate poor village girls. As well, Ellinor’s pupils learn to despise the empty pomp and vanity of the fashionable world after visiting with the snobbish Miss Harrington. The story ends rather abruptly and we are given no information about what happens to the Miss Somervilles or Miss Mountford or with Ellinor and her sister in the future.The Barbadoes Girl

Since this book must have been written before EKM died in 1802, its composition predates another book about a spoiled West Indian heiress who is sent to live with a family in England, namely, The Barbadoes Girl (1816) by Barbara Hofland, which I reviewed here.

In that tale, the bratty Matilda Hanson throws a glass of beer into her servant's face while sitting at the dinner table, to the shock of her hosts. Zebby speaks up in her defence:

“Poor Zebby, courtesying, said, ‘Sir, me hopes you will have much pity on Missy—she was spoily all her life, by poor massa—her mamma good, very good; and when Missy pinch Zebby, and pricky with pin, then good missis she be angry; but massa say only—‘Poo! Poo! She be child—naughty tricks wear off in time.’”

So after reading The Young West Indian, I was really scratching my head—is it just a coincidence that EKM came up with a plot about a spoiled West Indian girl who is abusive to her servant years before Barbara Hofland wrote a best-seller about a spoiled West Indian girl who is abusive to her servant? Hofland could not have copied EKM’s story since it wasn’t published until after The Barbadoes Girl, even though EKM’s version was written before. Was EKM just unfortunate in that she had the idea first, but her manuscript never saw the light of day until after her death? The original story

Well, I stumbled across a plausible explanation for how both authors could have written two very similar stories—both of these novels were probably written in emulation of a tremendously successful but now forgotten children’s book: The History of Sandford and Merton, first published in 1783. Sandford and Merton is the GOAT (as the kids say) version of a spoiled West Indian boy who comes to live in England and is reformed by wise precept and a bit of deserved suffering.

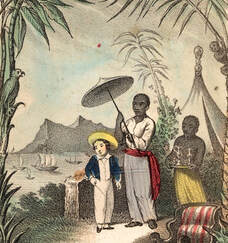

Here is author Thomas Day’s description of the protagonist: “Tommy Merton, who, at the time he came from Jamaica, was only six years old, was naturally a very good-tempered boy, but unfortunately had been spoiled by too much indulgence. While he lived in Jamaica, he had several black servants to wait upon him, who were forbidden upon any account to contradict him. If he walked, there always went two negroes with him; one of whom carried a large umbrella to keep the sun from him, and the other was to carry him in his arms whenever he was tired. Besides this, he was always dressed in silk or laced clothes, and had a fine gilded carriage, which was borne upon men's shoulders, in which he made visits to his play-fellows. His mother was so excessively fond of him that she gave him everything he cried for, and would never let him learn to read because he complained that it made his head ache.”

Day used the familiar formula for an instructive children’s books; that is, narrative interspersed with improving discourses, but his narration is livelier, more detailed, and features a plot with actual character arcs.

Day used the familiar formula for an instructive children’s books; that is, narrative interspersed with improving discourses, but his narration is livelier, more detailed, and features a plot with actual character arcs. Some of the educational material is woven more smoothly into tale. The boys’ tutor challenges Tommy with Socratic dialogues: "And pray, young man," said Mr Barlow, "how came these people to be slaves?"

Tommy.—Because my father bought them with his money.

Mr Barlow.—So then people that are bought with money are slaves, are they?

T.—Yes.

Mr B.—And those that buy them have a right to kick them, and beat them, and do as they please with them?

T.—Yes.

Mr B.—Then, if I was to take and sell you to Farmer Sandford, he would have a right to do what he pleased with you?

By the conclusion of this dialogue, Tommy vows he will never “will use our black William ill; nor pinch him, nor kick him, as I used to do.”

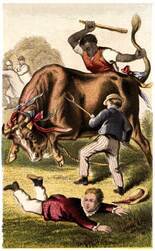

By the conclusion of this dialogue, Tommy vows he will never “will use our black William ill; nor pinch him, nor kick him, as I used to do.”A black sailor appears at the climax of the tale to help rescue Tommy from a charging bull. Unlike the servants in EKM and Hofland’s stories, he speaks in correct English, not pidgin: “Is a black horse thought to be inferior to a white one in speed, in strength, or courage? Is a white cow thought to give more milk, or a white dog to have a more acute scent in pursuing the game? On the contrary, I have generally found, in almost every country, that a pale colour in animals is considered as a mark of weakness and inferiority. Why then should a certain race of men imagine themselves superior to the rest, for the very circumstance they despise in other animals?”

More about Sandford and Merton in the next post. And who knows, I might come across more forgotten books with this type of plot in the future. Also, is there a connection to Jane Austen in all this? An 1823 short story by Mrs. Blackford, The Young West Indian, features the young son of an Army captain who behaves heroically when misfortune throws him and his baby sister into the power of an unscrupulous servant. Little William is not a typical sickly, spoiled Creole child as portrayed in the stories discussed here. The story mentions that British parents typically sent their children to be educated in England and that the heat and the ever-present fear of yellow fever made parents anxious for their children’s health.

These fictional portrayals of West Indian children appear drawn from real-life observations about the children of English settlers. According to scholar Chloe Northrop, “European observers noted the overindulgence exhibited in the progeny of the wealthy Caribbean elite, stemming from both their parents and others responsible for their upbringing… According to these narratives, [enslaved people working as nannies and caregivers] irrevocably spoiled the character of the young white inhabitants.

"Furthermore, at a young age, these children became accustomed to seeing violence against black slaves, including maimings and whippings.” Northrop, Chloe. Fashioning Society in Eighteenth-Century British Jamaica. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2024.

Rowland, Peter. “Unwelcome Company: Thumbs Down for Sandford and Merton.” The Wildean : Journal of the Oscar Wilde Society, no. 38, 2011, pp. 44–53.

Thank you to the Special Collection librarians at the University of Iowa. Previous post: Regency-era children's lit Next post: Three children's books, one plot

Published on September 29, 2025 00:00

No comments have been added yet.