The legacy and loss of Colorado’s once-mighty glaciers

High in the Indian Peaks Wilderness beyond her home in Boulder, Millie Spencer has been venturing to an extreme, jagged place of rock and ice.

“Especially since I became obsessed with this idea of watching its decline,” she said.

Like others before her, the Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado-Boulder has been drawn to the plight of what might be Colorado’s last glacier: Arapaho Glacier.

Others before her include Dan McGrath, a glaciologist and professor at Colorado State University. Earlier this month he joined a research flight over a dozen snowbound sites around the state — sites with “glacier” in their names but not meeting a scientific standard to be defined as such.

“More so snow fields or perennial snow and ice (patches) than glaciers,” McGrath explained. The fields were no longer masses large enough to subtly move under their own weight, as true glaciers do.

As Arapaho Glacier does, researchers suspect. McGrath also suspects Andrews Glacier does — perhaps the only correctly named “glacier” among several in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Andrews Glacier high in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Andrews Glacier high in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrathThe sign along Interstate 70 reads “St. Mary’s,” not “St. Mary’s Glacier,” as the popular destination has been popularly called.

“It used to be a glacier, I assume,” said Bruce Raup, the senior associate at the Boulder-based National Snow and Ice Data Center. “But it’s been a while.”

Colorado has been warming with the rest of Earth, and glaciers everywhere have been shrinking and vanishing. Melting glaciers are a major, well-documented source of sea level rise. A study between 2006-2016 quantified the global loss at around 335 gigatons a year — or enough glacial melt to fill close to 130 million Olympic-sized swimming pools a year, as McGrath has noted.

Tracking this loss has been a more recent mission of a database Raup oversees, called the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) initiative. Analysts at Rice University went with a more straightforward name for their database similarly in early development: the Global Glacier Casualty List.

It’s indeed “early days” for GLIMS, Raup said. “So only a couple hundred glaciers so far,” he said. “But we’re in the process of getting more data from various collaborators around the world.”

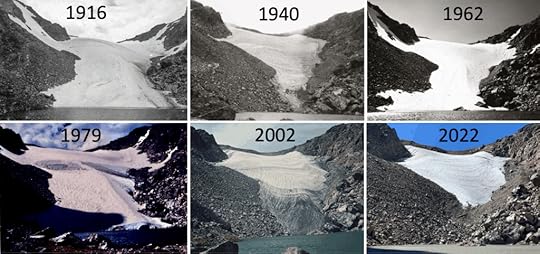

Including in Colorado. This month Raup flew with McGrath over those glacial sites, gathering imagery and adding to a collection that spans the last century. From around the turn of the 1900s to today, images show snow and ice drastically fading at Arapaho and Andrews glaciers.

Colorado State University professor and glaceologist Dan McGrath compiled these photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center showing changes over the years at Andrews Glacer. 1916 Willis Lee/NSIDC; 1940 Paul Nesbit/NSIDC; 1962 C.B. Harris/NSIDC; 1979 and 2002: Russell Allen/NSIDC; 2022 McGrath.

Colorado State University professor and glaceologist Dan McGrath compiled these photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center showing changes over the years at Andrews Glacer. 1916 Willis Lee/NSIDC; 1940 Paul Nesbit/NSIDC; 1962 C.B. Harris/NSIDC; 1979 and 2002: Russell Allen/NSIDC; 2022 McGrath.To Spencer, the images are “heartbreaking.” Why? That’s the question she’s been exploring.

As part of her dissertation, she’s been exploring the sociocultural impacts of disappearing glaciers in Chile. Glaciers are much bigger there and in other parts of the world compared with Colorado. And yet the emotional loss seems no lesser to Spencer.

Why? she has asked in a brief paper she’s drafted on Arapaho Glacier. She titled the paper “On Death and Dying.”

In summary, she said: “What does it mean to lose these parts of the landscape that contribute so much to our sense of place?”

Yes, glaciers have contributed greatly to Colorado.

Arapaho Glacier in Indian Peaks Wilderness. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Arapaho Glacier in Indian Peaks Wilderness. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath“The ruggedness of our mountains is a direct result of glaciers,” said Vincent Matthews, the retired director of the Colorado Geological Survey.

Last year he published a book, “Land of Ice: Jaunts into Colorado’s Glacial Landscape.” The book offers a crash course on eras of glaciation, including some 20,000 years ago, when snow and ice coated much of the Front Range. Glaciers thousands of years earlier carved the Rockies, leaving the kind of U-shaped valleys we see, for example, at the Maroon Bells.

It’s but one cherished scene depicted in Matthews’ book of “jaunts.” He suggests more road trips showcasing many more remnants of glaciers: the sculpted ridges, aretes and cirques of Rocky Mountain National Park, for example. Those features decorate the San Juan Mountains and the opposite, northwest mountains around Steamboat Springs, where Matthews points to a terminal moraine by the Walmart. He likes to call Turquoise Lake “the most famous terminal moraine.” He calls the Grand Mesa “a grand ice cap.”

Glaciers, he writes, could be thanked for shaping the corridors of our scenic highways. They could be thanked for the ski terrain we love. They could be thanked for some of our drinking water. And maybe glaciers could somehow be thanked for saving the world.

Referring to the U-shaped valley that was home to the 10th Mountain Division, Matthews writes: “Glaciers created the landscape that prompted the Army to select this area for training an elite force that played a key role in winning World War II.”

Camp Hale, like much of Colorado’s topography, is the result of a more recent period of glaciation referred to as the Little Ice Age. This was around the years 1650-1850, Matthews writes.

“Then the climate began warming again, and the glaciers retreated. Enjoy them while they survive.”

Moomaw Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrath

Moomaw Glacier in Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo courtesy Dan McGrathJust how much longer Colorado’s glaciers will survive — if any could still be called a glacier — has been of some debate this century.

Particular focus has centered on Arapaho Glacier, which has long captured the fascination of onlookers from Boulder.

An adventurous botanist, Herbert N. Wheeler, wrote of a visit in the summer of 1897. He wrote of walking across the ice and coming by cracks “at first a few inches wide and then several feet wide.” This was “rather terrifying,” he recalled. “We dropped rocks down into the crevasses but didn’t hear them strike bottom.”

However terrifying and immense, the glacier was probably retreating at that time, later researchers surmised.

Using imagery throughout the decades and modeling technology, University of Colorado-Boulder scientists found Arapaho had lost 52% of its area throughout the 1900s. This was documented in their 2010 paper, which also delved into climate data and projections, similar to a paper from a few years prior. Based in Rocky Mountain National Park, that 2007 paper concluded: “Glacier recession on the Front Range at present may be greater than at any other time in the historic record.”

Warming temperatures that shrunk Arapaho Glacier in the previous century were increasingly warming in this century, researchers wrote in 2010: “If recent trends in area loss continue, Arapaho Glacier may disappear in as few as 65 years.”

But the study pointed to peculiar, potentially sustaining aspects of the glacier’s position.

Arapaho is “in a protected cirque environment,” explained McGrath, the Colorado State University glaciologist. Thanks to surrounding mountains, “it’s topographically shaded,” he said, and often gaining snow from avalanches.

Compared with others globally, Colorado’s glaciers “are a little bit different in that they’re highly dependent on wind distribution of snow,” added Raup at Boulder’s National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Arapaho and Andrews glaciers benefit from snow-giving westerlies. And they benefit from high elevation temperatures that, amid warming, could keep precipitation falling as snow instead of rain, unlike other parts of the West.

That’s at least for the foreseeable future. Projections for seasonal snowpack “are quite, quite grim for later this century,” McGrath said.

And “without a doubt,” he said, “the loss of glaciers here in Colorado would impact local ecosystems.”

The perennial snow is essential to the pika, for example, and also to the white-tailed ptarmigan, which makes a seasonal home in the alpine. Many more animals and plants have counted on glacial melt feeding streams downslope.

Arapaho Glacier’s perennial runoff has also fed Boulder’s drinking water supply — “miniscule when compared to the relative contributions of rain and seasonal snow,” Spencer, the Boulder Ph.D. student, wrote in her brief.

No matter that small impact, “On Death and Dying” seemed the right title for the paper. Because “the sociocultural impact of the glacier’s death is immense,” Spencer wrote.

On her regular ventures to Arapaho, she’s met skiers missing the snow they once knew. She’s met longtime hikers. “They’ll bring up pictures they have of their family there in the ’50s at the top of the glacier, and how different it looks today,” Spencer said.

She hasn’t been around that long; she’s only seen the loss in those photos. And yet hiking to Arapaho somehow feels sad and nostalgic, she said.

“Maybe it’s more like secondhand nostalgia, and I’m mourning this experience that I may not get to always have,” she said. “Or if I have a kid, knowing these glaciers might not be around for the next generation. They might just be stories passed down.”

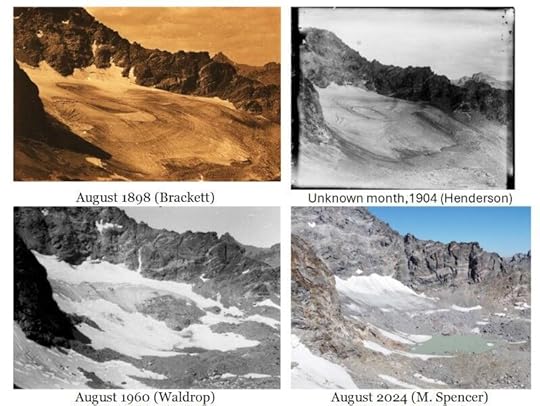

University of Colorado-Boulder PhD candidate Millie Spencer compiled these photos showing changes at Arapaho Glacier over time. The photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center are from 1898 (Brackett); 1904 (Henderson); 1960 (Waldrop); and 2024 (Spencer).

University of Colorado-Boulder PhD candidate Millie Spencer compiled these photos showing changes at Arapaho Glacier over time. The photos from the National Snow and Ice Data Center are from 1898 (Brackett); 1904 (Henderson); 1960 (Waldrop); and 2024 (Spencer).