Picket Shots of Chickamauga from the Army of the Cumberland

In "Picket Shotsof Chickamauga" I'll share some of the shorter stories provided by veterans of the Chickamauga campaign that might not be long enough to constitute a blog post on their own, but make for insightful reading.

In commemoration of the 162nd anniversary of the opening day of the battle, three accounts below give some perspectives from soldiers in the Army of the Cumberland, including Henry Dietrich of the 19th Illinois, Allen Fahnestock of the 86th Illinois, and Edward Molloy of the 87th Indiana. Tomorrow's post will feature three stories from their opponents in the Army of Tennessee.

Brotherton Cabin

Brotherton CabinAt the Battle of Chickamauga, I was a private in the ranks ofCo. A of the 19th Illinois Infantry. I was one of the skirmisherssent out to feel the enemy. At the beginning of the battle, we advanced towardsa clump of woods to draw the fire of the Southerners. We had to cross a fieldcovered with stumps and piles of rails and a battery was stationed behind us tothrow shells into the Confederate ranks whenever we should draw their fire.

We had advanced a considerabledistance when the Confederates opened on us. We took refuge behind the railsand remained there firing until the recall was sounded. The battery all thewhile threw shells over us and into the woods. When we were going back afterthe recall, I missed a young soldier named Metcalf. Looking back, I saw himkneeling behind a rail pike. Another soldier and myself, thinking he must bewounded, we went back to get him. We found that a short shot from our ownartillery had literally blown off the top of his head but it had not caused himto fall. [The Illinois Adjutant General’s report states that Private Fred W.Metcalf was killed in action September 11, 1863, at Lafayette, Georgia.]

Private Henry S. Dietrich

Private Henry S. DietrichCo. A, 19th Illinois Inf.

On Saturday night September 19, I wason outpost duty. When relieved at midnight, I was thoroughly chilled. I wentback toward my company and on the way came upon a soldier lying beneath ablanket. Not having a blanket of my own, I crept under his blanket quietly tokeep from disturbing him. I did not awaken until morning. Then I turned to geta glimpse of my companion. He was a dead cavalryman and I had slept beside himthinking he, like myself, was only worn out from the day’s duties.

The next day, on Sunday September 20th,I had my experience in terrific fighting. Our regiment that day occupied SnodgrassHill, the key to the situation. There we remained until night. To make ourposition secure and afford us some protection, we tore down fences and log cabinsand built a walk just high enough to hide us when lying down. Immediatelybehind us were the cannons. Men still back of the cannons loaded our guns andpassed them to us and we reserved our fire for the charges which theSoutherners repeatedly made. At one time I had five loaded guns beside me. Whenthe enemy would come very close, we would fire these reserve guns as fast as wecould pick them up and take aim. The cannons boomed right over us all the timeand deafened several of the soldiers.

Source:

“Incidentsof Chickamauga,” Private Henry S. Dietrich, Co. A, 19th IllinoisVolunteer Infantry, New Washington Herald (Ohio), December 18, 1903, pg.12

Colonel Daniel McCook

Colonel Daniel McCookThe FirstShots of Chickamauga

There is no question in my mind as towho opened the fight at Chickamauga. Our regiment, the 86thIllinois, went out with Colonel Dan McCook’s brigade on the evening ofSeptember 18, 1863, to destroy Reed’s Bridge across the Chickamauga. CompaniesB and I of the 86th Illinois were on picket on the right of theLafayette Road with Co. B under Captain [James P.] Worrell on my left and 20men of the 52nd Ohio on my right. The much-talked-of spring lay tothe left of Captain Worrell’s company.

Lieutenant [Richard W.] Groinger ofthe 86th and myself took charge of our post that night as I wasshort of men. I told Private Jacob Petty of my company that evening that therewould be a fight the next morning and said to him that if he shot a Johnny, Iwould buy him a plug of tobacco. The next morning at break of day, a Confederatecavalryman rode to our front. Petty saw him and asked Lieutenant A.A. Lee if heshould shoot. Lee said yes. Petty fired and brought down his man and that shotopened the Battle of Chickamauga.

Capt. Allen L. Fahnestock

Capt. Allen L. FahnestockCo. I, 86th Illinois

Soon after Petty’s shot, firing beganon the left of Co. B at the spring. Captain Swift of Colonel Dan McCook’s staffhad ordered me to the top of the hill to fight the enemy back to the brigadeand Barnett’s battery. We carried out instructions to the letter but when wehad driven the enemy to where the brigade had been posted, there was no brigadethere. It had been ordered back as the enemy had crossed Chickamauga Creekabove and below and now pressed my small force on both sides.

About this time, General Thomas on myright or south of Reed’s Bridge, struck the enemy and the fighting becamegeneral. I claim that our brigade should have the credit of opening the Battleof Chickamauga and I contend that we closed it on the night of the 20that Cloud Springs, to my mind the key to the Union position. Petty, who firedthe first shot on the 19th, claimed his reward that evening.Lieutenant Lee notified me that Petty had got his man and wanted his plug oftobacco. Tobacco was scarce at the time, but I found a plug and paid $1 for itand sent it to Petty. The U.S. is indebted to me for that amount plus interest for42 years.

Source:

“Memories ofthe War,” Captain Allen Lewis Fahnestock, Co. I, 86th IllinoisVolunteer Infantry, Hocking Sentinel (Ohio), February 8, 1906, pg. 3

TheNarrow Escape that Led to Capture

The regiment to which I belonged, the87th Indiana, suffered a loss of 51% at the Battle of Chickamauga.Eight commissioned officers were killed and others were wounded. The sight thatmorning just before the battle opened was worth seeing. The 87thIndiana stood in close column by division facing a piece of woods. Just as thebattle opened, first a stray shot or two, then a roll of musketry, next theterrific roar of artillery.

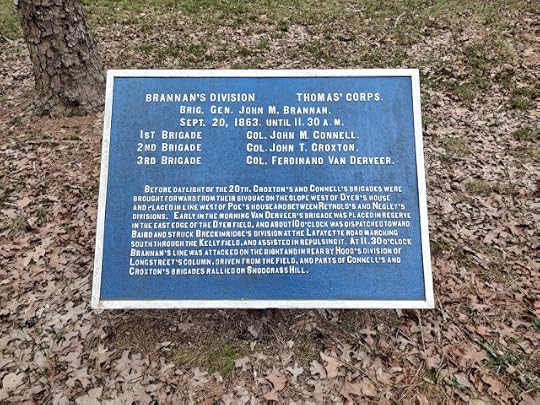

General Rosecrans rode by with his staff and bodyguard,presenting a magnificent appearance. The general wore a sombrero and sat on hishorse as if he were monarch of all he surveyed. Just in the rear of thecommanding general was General Thomas and his entire staff, occupying a risingpiece of ground. A shell flew over us and reached the ground over whichRosecrans and his grand cavalcade were passing, but not a man dodged. Presently,General Garfield, simply armed with a huge field glass, rode over to ourregiment and inquired for General Brannan, the commander of our division.Adjutant Ryland replied, “General, I think he just rode into the woods,”pointing his finger in the direction indicated and that was the last we eversaw of any of those gallant generals referred to whose deeds of valor form sucha conspicuous and thrilling portion of our nation’s history.

The morning of September 20, 1863, the 87thIndiana and the Confederates confronting the regiment fairly fired into eachother’s faces. This is the united testimony of General Hazen of West Point andColonel Vanderveer of the 35th Ohio who commanded the brigade ourregiment was in at the time. General Hazen declared that he never before sawmen fire in each other’s faces as he did at Chickamauga except at the Battle ofShiloh, but there bushes intervened between the lines while at Chickamauga, thetroops of both armies fairly confronted each other.

Those who remained with the 87thafter the first encounter that morning stated unhesitatingly that theConfederates literally left the ground covered with their dead and wounded. Itwas a heroic struggle on both sides. The men of both armies stood their groundwell. Judging by the loss of the 87th during that morning’s dreadfulencounter and a casual glance at the depleted numbers as they started inpursuit of the Confederates, the 87th seems to have fairly meltedaway. The dead lay where they fell while the wounded sought some place wheretheir injuries could be attended to.

As I left the regiment on the forenoonof September 20 by reason of being wounded in the leg, I beheld some wonderfulsights. Just as I started, Pete Heminger of Mishawaka rushed past me anddropping on the ground exclaimed, “Oh, for God’s sake, give some water! I’mshot through and though!” The front of his blouse was covered with blood. Thecomrade who was assisting me, having no water in his canteen, I requested himto take my canteen and quench the thirst of the dying soldier.

Wounded comrades were hastening to therear from all sides. Presently, I encountered a commissioned officer who wasskulking. Next, two horsemen approached me, one shouting at the otherexcitedly, “For God’s sake, bring back that flag!” Off to the left, the Uniontroops were retreating in great disorder, the men running like frightenedsheep. It was evidently the time and place when and where the Confederates penetratedour lines, dividing our army. As I reached Chattanooga road, I beheld a perfecttraffic jam of wagons, caissons, and ambulances. Shells were flying overMission Ridge just to the left of the road and much confusion prevailed.

I perched myself on the lower step ofan ambulance but did not persist in remaining there as I deemed it hopeless toattempt to reach Chattanooga that way. So, I retreated into the woods after restingfor a short time and tried to persuade some comrades who were playing cards to helpme to the road I had just left. I thought it possible that I might procure passageto the city in some way not readily discernible, but the “brave” heroes ignoredme completely, so I was compelled to do the next best thing- help myself, whichI did by discarding everything but my canteen and haversack.

I walked quite a distance, although I was shot through theright leg just under the knee where the bullet narrowly missed an artery andboth cords of the limb. But excitement kept me up till I reached a stoppingplace where the surgeon pronounced the leg wound a “narrow escape.”

That night I slept in bed with a dead man, First SergeantSolomon E. Harding of LaPorte. He belonged to Co. G of the 87th andwas twice wounded, one or both wounds being mortal. At any rate, he passed awayat 2 a.m. after much suffering and when I awoke at daylight, he was cold indeath. That morning I was captured, the Union troops having fallen back in thenight leaving myself and the other wounded Union soldiers between the lines. Iwas on my way to Chattanooga when taken prisoner, the surgeons having advisedall of us that could do so to try and reach that place. Before starting, Iturned over all my rations to those left behind and the consequence was Inearly starved to death before being paroled and transferred to the Unionlines.

There was no attention paid to the wounded by theConfederates and no provision made for supplying prisoners with food until thelast two days that I was in their lines. Then something we designated as “slop”was issued to us. It was not thick enough for mush and too thin for gruel. Ithink it was made of bran and was cooked in large iron kettles used in thearmy. The prisoners were supplied with this three times a day. The kettles werepassed around and you helped yourself by dipping your cup into the kettle as itreached you. Each soldier was allowed to dip his cup in only once during ameal. If you were so fortunate as to possess a large cup, you received a largecupful, otherwise not.

Source:

“One of theWar’s Greatest Battles: Men Literally Fire Into Each Other’s Faces,” PrivateEdward Molloy (later Adjutant), Co. I, 87th Indiana VolunteerInfantry, South Bend Tribune (Indiana), May 22, 1912, pg. 4

To learn more about the Chickamauga campaign, please check out the Battle of Chickamauga page where you'll find more than 100 blog posts covering varying aspects of this important campaign.

Daniel A. Masters's Blog

- Daniel A. Masters's profile

- 1 follower