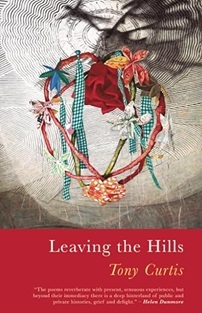

Review of Leaving the Hills, by Tony Curtis, pub. Seren 2024

Tony Curtis has now been active in poetry for some 50 years, and as might perhaps be expected, this collection is very retrospective, sometimes elegiac, in tone. There are many childhood reminiscences, tributes to departed friends like Dannie Abse, Helen Dunmore and Glyn Jones, and poems centring on the history of Carmarthenshire, where Curtis grew up. To quote (in translation) the Welsh poet J T Jones, a man in old age is drawn to the scenes of his youth, “to walk in the places where he used to run”. But Curtis has also been a much-travelled man, and this is reflected in poems set in the US and Europe.

In poems like “Visiting the Big Man”, the elegiac tone is very pronounced:

We looked across the fields

for what had gone

and what we’d never see again.

That would have been the last time

I saw him, or maybe the time

before the last time.

Those three “time” line endings strike like hammers, or the tick of a clock, emphasising both the passing of time and the fallibility of memory.

But though the poet is necessarily conscious of mortality (even, in “Further instructions”, leaving guidance for the disposal of his ashes), elegiac does not have to mean unremitting gloom, and these memories are mostly positive. There is keenly observed nature,

Sparrows bicker in the bankside bramble (“The Guardian”),

and the “Bosherston Pike”,

angling through the lily roots,

Razor teeth and steel-clasp jaws

Cruising the pools like a U-Boat in the shadows.

There are intriguing “characters” from the past, like Jimmy Wilde and Anne James. There is also the present, in the form of grandchildren and, still, new experiences:

stare up through the huge pines and meet

a sky that comes down to greet us

with its diamonds closer,

bright and sharp and beyond number,

met as if for the first time. (“Yosemite”).

Having said that, there is undoubtedly a dark streak running through the collection, perhaps best exemplified in the often ambiguous and mood-changing endings of some poems. From that of “Railroad – “blood and dreams. Everything we need/ it seems” to the sinister double meaning in the last line of “In the Duomo, Siracusa”:

out of the body in death, that motherly caress,

the waiting over, knowing your depth

and it’s taking you in.

“Scrolling Down”, a list poem which is his one concession to the internet age, didn’t really work for me; it highlights the random nature of news stories and the way they manage to equate the vital and the trivial, but we all knew that. There are, inevitably in a retrospective like this, a great many personal references, especially to friends and acquaintances. I know from experience that this can sometimes irk readers (or maybe it’s just reviewers), but it really shouldn’t, as long as the writer has managed to find the universal in the particular. We have all lost friends and relatives; all found inspiration in odd corners of history, and we should be able to mentally substitute the names in our own experience for those in the poem. I was reminded a couple of times of a review of one of my own collections, which opined that it wouldn’t please any reader who was “not interested in history”. I think that is true of this collection too, but then I can’t actually imagine what such a person would be doing reading any kind of a book.