Against Amnesia: Walking with Ignazio Gardella

Ignazio Gardella (born Mario in 1905 – 1999) was one of the most incisive and restless figures of Italian modernism, a man who managed to embody both rigour and a certain dose of rebellion (though never enough to convince him not to serve the Fascists, for which we should never condone anyone).

Born in Milan into a dynasty of engineers and architects, Gardella never settled for a single stylistic formula: his career stretched from rationalist beginnings in the 1930s, through the experimental postwar reconstruction years, to a late capacity for contextual and civic architecture. What makes him especially relevant to Milan is that the city itself became both his testing ground and his laboratory: his buildings are scattered across its urban fabric like traces of a long conversation between modernity and memory.

A Milanese Humanist of Modernism

A Milanese Humanist of ModernismUnlike many of his contemporaries who either resisted the weight of history or drowned in it, Gardella had a subtle way of weaving past and present. His Casa Tognella along Parco Sempione, with its clean rationalist lines tempered by refined detailing, is a lesson in how to innovate without erasing. His Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (friendly known as PAC) is another symbol: bombed in 1993, later restored under his guidance, it embodies the idea that architecture can absorb trauma and still stand as testimony.

The Pavillion for Contemporary Art in Milan, friendly known as PAC

The Pavillion for Contemporary Art in Milan, friendly known as PACThis duality — innovation with continuity — is what Milan desperately needs to remember today, as it pushes forward with unrelenting urban transformations that too often sacrifice legacy in the name of progress.

A Web of Influences and FriendshipsGardella was not isolated: he belonged to a generation of architects who debated, disagreed, and built Milan together. With Luigi Caccia Dominioni, he shared both professional ground and a spirit of discreet elegance: architecture as urban civility, where modern buildings coexist with the texture of historic streets. Together, they founded Azucena, one of the first design companies of our age.

With Luciano Visconti, the famed film director, Gardella found another kind of kinship: Visconti’s cinematic realism and Gardella’s architectural clarity both sought to reveal the dignity of the ordinary, grounding modernity in lived experience.

Why am I upset?Ah, you’ve noticed. It’s only the last of a series of operations that almost completely destroyed the modernist masterpieces in the historical fair area, now Citylife, with its beautiful park and fucking ugly skyscrapers. The operation was strongly pushed by the last right-wing administration we had in the city — the major being one of the women who destroyed public schools before merrily moving on to try the same on my city — and its victim was the historical fair with the exception of some cherry-picked buildings which were deemed worthy of survival. These buildings, even at the time, did not include the groundbreaking aeronautical pavilion, for instance, because its author wasn’t well-known and well-connected.

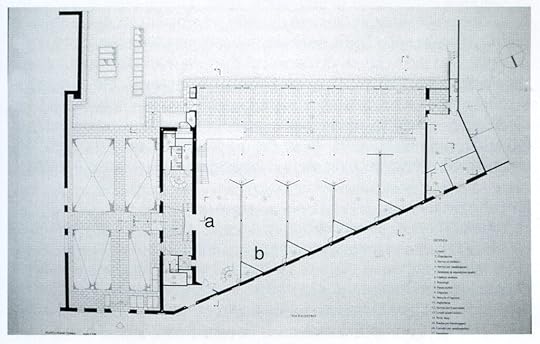

A shot of the historical fair

A shot of the historical fairIn late July 2025, Milan witnessed another erasure: the Agriculture Pavilion (Padiglione dell’Agricoltura) designed by Ignazio Gardella and erected in 1961. What once stood along via Gattamelata as the modernist hallmark of the post‑war expansion of the Fiera Campionaria — its graceful “Palazzata” façade articulated in Vicenza stone, dark red clinker, and a double‑height glass wall with vivid red‑framed steel — was reduced to rubble to make way for a new RAI Production Centre set to open in 2029. Despite its inclusion in the Lombardy cultural heritage inventory, the Pavilion lacked the 70‑year threshold required by preservation law to prevent demolition. Thus, legal protection fell short, and history was deemed expendable. You can read more about it here. They’re as angry as I am.

This was not an unexpected collapse of structure or identity, but a planned amputation, part of the area’s redevelopment strategy that has already swept away most of the old Fiera complex, replaced by the towering silhouettes of CityLife. The Pavilion’s disappearance marks the final chapter of the classic Fiera Campionaria in that corner of the city. No, Palazzo delle Scintille doesn’t count.

Palazzo delle Scintille was here before the historical fair, as a sports facility. Besides, it’s liberty, which means it’s respectable.

Palazzo delle Scintille was here before the historical fair, as a sports facility. Besides, it’s liberty, which means it’s respectable.Milan, in its rush to reinvent itself, often brands these gestures as “riqualificazione urbana,” as if rejuvenation can only happen by erasing layers of the past. Yet when that impulse goes unchecked, it becomes self-sabotage: a city that refreshes its façade at the expense of its memory. The loss of Gardella’s Pavilion is not just an architectural casualty, but a civic one, a rupture in the continuum that binds one generation’s forward thinking to the next generation’s sense of place.

This is why this week I take you through the city with an urban itinerary that touches what’s left of Gardella’s legacy. Take my hand, wear your best shoes, and let’s hit the road.

Core Landmarks (in the City)Stop 1: Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea (PAC), Via PalestroThe PAC was commissioned in the early 1950s as part of a postwar civic initiative to provide Milan with a dedicated venue for contemporary art exhibitions. Located on Via Palestro, right next to the Villa Reale and its historic gardens, the building was deliberately conceived as a modern counterpart to the neoclassical fabric around it. In 1993, the pavilion was heavily damaged by a bombing targeting the adjacent Villa Reale. Its destruction could easily have meant the disappearance of another piece of Milan’s architectural memory, but the city chose to restore it and turned again to Gardella himself to lead the work. I studied the building as an architectural student and you have a longer description in this old blog post.

The pavilion’s interiors.

The pavilion’s interiors.Gardella conceived the pavilion as a light, rational structure: an elegant steel skeleton, brick infill, glass expanses, and a modular grid system that allowed flexibility for exhibitions. Unlike the monumental rhetoric of fascist-era pavilions, this was a human-scaled, transparent, and welcoming civic space. After the bombing, Gardella (with his son Jacopo) restored and subtly reinterpreted the building. He preserved its core spirit — the transparency, the rational grid, the fluidity of the interiors — while reinforcing and modernising the structure. The restoration itself became an architectural statement: a refusal to let terror erase culture.

Another shot of the interiors.

Another shot of the interiors.The significance of the PAC lies not only in its architecture but in what it represents for the city. Gardella managed to merge rationalist rigour with a uniquely Milanese sense of refinement, producing a building that is modern without ever becoming brutal, transparent without lapsing into naïveté. Standing beside the Villa Reale, the pavilion engages in a dialogue across centuries: neoclassical monumentality converses with postwar modernity, each reinforcing the other rather than cancelling it out. When that dialogue was tested by tragedy, its restoration transformed the PAC into a civic symbol of resilience, proof that Milan could absorb violence without relinquishing memory. In this sense, the pavilion is not simply a container for contemporary art but one of the city’s strongest metaphors for memory as resistance. Today, as other modernist landmarks fall under the banner of “renewal,” the PAC stands as a reminder that progress can also mean restoration, care, and continuity, that the future need not be built on erasure.

Stop 2: Casa Tognella (Casa al Parco), Via Paleocapa / Via Ricasoli

Stop 2: Casa Tognella (Casa al Parco), Via Paleocapa / Via RicasoliBuilt between 1947 and 1953 on the edge of Parco Sempione, Casa Tognella, often called Casa al Parco, was one of the first private residential buildings to rise in Milan after the devastations of the Second World War. Commissioned by the industrialist Antonio Tognella, it occupies a privileged site overlooking the park, where the scars of bombings and demolitions left both a void and an opportunity. The building immediately attracted attention because of its bold departure from traditional apartment houses of the time, presenting itself as a manifesto of the city’s rebirth. I’m not particularly fond of this one, but the main facade surely has merit for a student.

My favourite facade.

My favourite facade.Ignazio Gardella approached the project with a strong sense of experimentation. Instead of reproducing the decorative formulas of prewar Milanese housing, he designed a slender, transparent structure defined by its large ribbon windows, floating terraces, and a rhythmic façade grid that was both rational and elegant. Technically, it was one of the earliest uses in Milan of pilotis and curtain walls, while still maintaining the compositional discipline of traditional Italian palazzi. Gardella treated the building almost as a laboratory of new urban dwelling: open plans, flexible interiors, and a façade that broke with masonry heaviness in favour of lightness and permeability.

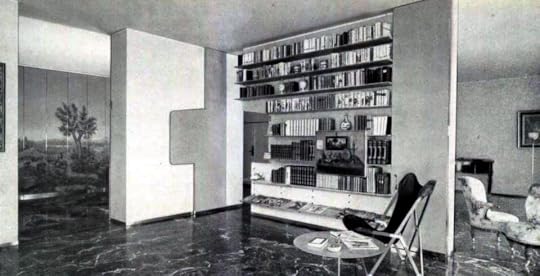

The interiors were absolutely stunning.

The interiors were absolutely stunning.The importance of Casa Tognella lies in its role as a threshold between eras. It is not simply a modernist block transplanted onto a historic park edge. Gardella’s façade, suspended between rigour and lightness, asserts that Milan could move forward without ignoring the weight of its setting. Its presence alongside Parco Sempione is almost polemical: housing could be both modern and urbane, technical and refined. In a city that was eager to rebuild quickly, Gardella insisted on a form of architecture that was neither nostalgic nor reckless, but attentive: a rare quality in the postwar climate.

What makes the building resonate today is precisely this refusal to choose between past and future. Casa Tognella demonstrates that the dignity of everyday housing can embody architectural innovation, and that context is not a burden but an interlocutor. In the activist framework of this itinerary, it serves as an early warning against the dangers of amnesia. Just as the PAC later proved that restoration could be progress, Casa al Parco already showed that innovation could coexist with continuity. In both cases, Gardella’s lesson is the same: Milan’s strength lies in its ability to transform without erasing.

Stop 3: Casa in Via Marina 3–5 (Casa Bassetti), 1960–62

Stop 3: Casa in Via Marina 3–5 (Casa Bassetti), 1960–62In the early 1960s, Milan was consolidating its image as Italy’s financial and cultural capital, and the area around Via Marina, bordering the Giardini Pubblici, became a prime location for high-profile residences. Unlike the urgent, experimental postwar works such as Casa Tognella, the Via Marina commission arose in a moment of relative economic stability and increasing demand for refined, prestigious housing. Gardella collaborated here with architect Roberto Menghi, another key figure of Milanese modernism, to create a building that responded not only to the functional needs of its inhabitants but also to the delicate urban setting facing one of the city’s green lungs.

[image error] Again, not my favourite building.Gardella’s hand is evident in the building’s measured balance between modern typology and Milanese sobriety. The structure is articulated through vertical partitions and horizontal ribbon windows, producing a façade that is rigorous yet softened by the rhythm of projecting loggias and set-back surfaces. Materials are chosen with care: exposed concrete and brick are combined with refined finishes, ensuring that the building feels both solid and elegant. Inside, apartments are organised with flexibility and light, designed to satisfy the expectations of a growing bourgeoisie who wanted contemporary spaces without giving up domestic comfort.

The Via Marina residence marks a turning point in Gardella’s trajectory, revealing his ability to adapt modernist principles to a more mature, almost classical language of urban dwelling. Where Casa Tognella had shocked the Milanese landscape with its radical lightness, Via Marina tempers innovation with composure, establishing a relationship with the tree-lined avenue opposite.

Its significance lies in this subtle negotiation. The building demonstrates that Milanese modernism was never about stylistic purity alone, but about dialogue with the city’s atmosphere: its rhythms, its materials, its understated elegance. For an activist itinerary, Via Marina is the reminder that preservation is not only about monuments but also about the quieter layers of the city’s architectural palimpsest. If works like these are allowed to vanish under speculative redevelopment, Milan loses not just individual buildings but the continuity of its civic character. Gardella shows us here that the future of housing in Milan could be modern and prestigious without severing its ties to the urban and cultural fabric that gave it meaning.

Stop 4: Casa in Via Marchiondi, c. 1950s

Stop 4: Casa in Via Marchiondi, c. 1950sThe postwar years in Milan were marked not only by the reconstruction of cultural landmarks and prestigious residences but also by an urgent demand for affordable housing. Entire swathes of the city’s periphery were being developed to host working- and middle-class families migrating from rural Lombardy and southern Italy. It was in this climate that Gardella contributed to the Via Marchiondi housing project, one of several experimental social housing complexes in the expanding northern districts of the city.

Take a look at the interiors.

Take a look at the interiors.Gardella approached the project with the same seriousness he reserved for more prestigious commissions. Instead of creating anonymous blocks, he sought to combine functionality with dignity, designing buildings that were structurally efficient but still responsive to light, ventilation, and the articulation of communal space. The façades, though simple, were carefully proportioned, relying on rhythm and subtle variation in fenestration to avoid monotony. His intervention in Via Marchiondi reveals his commitment to the ethical role of architecture: even mass housing deserved refinement, and even repetition could hold beauty if guided by proportion.

On the project, he worked with Anna Castelli Ferrieri, and their relationship will leave a beautiful testament in the Kartell headquarters and museum, just outside Milan, still being used today.

The Via Marchiondi housing block is thus significant because it illustrates how Gardella understood architecture as a continuum, not a hierarchy. He did not reserve innovation for villas or museums; he extended it to the everyday homes of ordinary citizens. In this sense, Giardini d’Ercole is as political as it is architectural. It demonstrates that the city’s peripheries were just as deserving of thoughtful design as its elegant boulevards.

For Milan today, which often treats peripheral housing as disposable, this lesson is crucial. To safeguard buildings like Marchiondi is to recognise that collective memory does not reside only in landmarks or in glossy downtown interventions, but also in the quieter architectures that shaped the daily life of thousands. Losing them to speculation or neglect is another form of civic amnesia. Gardella’s insistence on designing dignity into even the most constrained briefs is an activist manifesto in itself: the city betrays its future when it erases the fabric of its ordinary past.

Stop 5: Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, Via dei Ciclamini 34 (1965–70)

Stop 5: Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, Via dei Ciclamini 34 (1965–70)During the 1960s, Milan was experiencing rapid economic growth, but also the demographic transformations that came with it: an ageing population, new forms of welfare, and the need to rethink facilities for social care. In this context, the Casa di riposo “Antonietta Biffi”, located in the Barona district on Via dei Ciclamini, emerged as a crucial experiment. Instead of relegating the elderly to anonymous or hospital-like institutions, the project aimed to offer a residential environment that combined functionality with a sense of belonging and dignity.

Gardella’s contribution was to apply his hallmark balance of rationality and humanity. The building is organised around courtyards and green spaces, allowing residents to remain in touch with nature and light — a deliberate rejection of the claustrophobic typologies common to many care facilities of the period. The façades are sober but carefully articulated, using brick and concrete in measured proportions, while interiors are structured to foster both privacy and communal interaction. The architecture here does not patronise or isolate its inhabitants; instead, it acknowledges ageing as a phase of life deserving spaces of beauty, comfort, and continuity with the city.

Stop 6: Università Bocconi, Milan (Aula Magna and New Building, 1949–1956)In the aftermath of World War II, Milan was not only rebuilding its physical infrastructure but also reasserting itself as a capital of knowledge and innovation. The Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, which had been founded in 1902, needed new spaces to host its growing student population and reaffirm its role as a hub for Italy’s economic and managerial elite. The commission to design the Aula Magna and associated teaching facilities was given to Ignazio Gardella in the late 1940s.

The site was delicate: Bocconi’s historic campus lay close to the city centre, and the architecture had to reconcile institutional gravitas with the modern identity that Milan was beginning to project in the 1950s.

Gardella designed the Aula Magna and the adjoining blocks between 1949 and 1956. The project is emblematic of his ability to calibrate modernist principles with contextual sensitivity. The Aula Magna presents itself as a rational, monumental hall, with a façade of measured verticality and stone cladding, designed to convey the seriousness of the institution. Inside, however, Gardella allowed a warmer, more dynamic atmosphere to emerge, thanks to careful attention to acoustics, light, and materials.

His design provided Bocconi with not only a functional lecture hall but also a symbol of intellectual prestige — an architectural statement that learning was central to Milan’s reconstruction and modernisation. Unlike the residential experiments of Casa Tognella or Via Marina, Gardella embraced a more formal language, but without lapsing into authoritarian monumentality. Instead, the building retains a sense of accessibility and openness that reflects the democratic ideals of postwar education.

The Bocconi commission is significant because it illustrates Gardella’s ability to scale his architectural ethos to an institutional level. The Aula Magna is not simply a box for lectures but an urban forum, where the city’s future leaders gathered and where Milan declared its ambition to be an intellectual and economic powerhouse.

What makes it resonate today is its balance of gravity and lightness: monumental enough to embody authority — because the weak ego of Academia apparently demands that — yet still deeply rooted in human scale and experience. In the activist framework of this itinerary, the Aula Magna stands as proof that Milan once invested in architecture as a civic gesture, not just a private asset. At a time when universities increasingly outsource their identity to anonymous international models, Gardella’s Bocconi project shows that educational buildings can carry cultural memory as well as functional purpose. To preserve and value this work is to defend the idea that institutions, too, are part of the city’s collective history — and that their architecture should express continuity rather than rupture.

Studio Nonis recently touched up on the interiors (see here).

Stop 7: Residenze Mangiagalli II, Via De Predis 11 (1950–1952)

Stop 7: Residenze Mangiagalli II, Via De Predis 11 (1950–1952)Alongside prestigious commissions in the city centre, a vast program of residential expansion was underway to provide housing for middle-class families. The Mangiagalli II residences, located in the northwestern quadrant of the city near Via De Predis, formed part of this effort. They were conceived not as isolated buildings, but as fragments of a new neighbourhood fabric, combining efficiency with livability.

The project was entrusted to a team that included Ignazio Gardella and Franco Albini, one of my favourite designers of that time. Their collaboration exemplified a shared vision: that rationalist architecture could be humanised and adapted to the everyday needs of urban life.

Within this collective framework, Gardella contributed his characteristic attention to façade rhythm and proportional refinement. Where Albini leaned on structural clarity, Gardella nuanced the elevations with materials and details that softened the impact of repetition. The blocks were organised to maximise light, ventilation, and views, avoiding the monotony that too often plagued postwar housing. He sought to give dignity to each dwelling unit while still ensuring the overall coherence of the complex.

The project is therefore less about individual architectural flourish and more about the careful orchestration of everyday architecture, a field in which Gardella excelled, treating even the most modest commissions with the seriousness of a cultural act.

The Mangiagalli II residences are significant because they embody the ethical turn of Milanese modernism in the early 1950s. Unlike luxury projects such as Casa Tognella or Via Marina, here the challenge was to design affordable, efficient housing without surrendering quality. Gardella’s façades, disciplined yet varied, show that repetition need not mean anonymity. The complex becomes a lesson in how to humanise density, producing an urban fabric that could stand the test of time.

Stop 8: Stazione di Milano Lambrate (1983–1999)

Stop 8: Stazione di Milano Lambrate (1983–1999)By the 1980s, Milan was no longer the city of postwar reconstruction, but a metropolitan hub grappling with the demands of mobility and decentralisation. The Lambrate railway station, located in the northeastern quadrant of the city, had long been an important node on the line connecting Milan with Venice and beyond. A decision was made to replace the old facility with a modern passenger station that could serve the growing volume of daily commuters.

The commission went to Ignazio Gardella, working in collaboration with his son Jacopo and architect Mario Valle. It was among Ignazio’s last major projects, stretching across the final two decades of his career until its completion in 1999, the same year of his death.

Gardella approached the station as both a technical and civic work. Rather than treating it as an anonymous transit facility, he sought to give the building a clear architectural identity. The design features a large glazed concourse, framed by strong structural elements, allowing natural light to flood the interiors. The hall is flanked by cantilevered roofing and bold geometries, emphasising clarity of circulation and a sense of openness.

Materials are handled with Gardella’s usual balance of rigour and warmth: exposed concrete, brick, and glass combine to produce an environment that is robust but not alienating. Unlike many late-20th-century stations, Lambrate is legible, accessible, and designed with the commuter in mind.

The OutskirtsStop 9: Chiesa di Sant’Enrico, Metanopoli (San Donato Milanese), 1962–65

The OutskirtsStop 9: Chiesa di Sant’Enrico, Metanopoli (San Donato Milanese), 1962–65In the early 1960s, the powerful oil company ENI under Enrico Mattei was developing Metanopoli, a planned community in San Donato Milanese, just outside Milan. This company town was conceived as both a residential and cultural hub for ENI employees, embodying the utopian belief that industry could generate a new model of society. As part of this urban plan, ENI commissioned a parish church, dedicated to Sant’Enrico, which was intended to serve as both a spiritual centre and a symbolic anchor for the new community.

Ignazio Gardella designed the church between 1962 and 1965. His approach was strikingly modern: instead of reproducing traditional ecclesiastical forms, he opted for a geometric composition of volumes, centered around a tall brick tower and a nave expressed in bare, almost ascetic materials. The plan is rational and clear, built around an elongated hall with strong vertical accents. Brick and exposed concrete dominate, giving the building a tactile presence while avoiding decorative excess.

The interior is lit by carefully controlled apertures, producing a spiritual atmosphere through light rather than ornament. Gardella’s design reflects a theology of sobriety: the sacred is not conveyed by gilded altars but by proportion, rhythm, and the subtle modulation of space.

Stop 10: Chiesa di San Nicolao della Flue, Via Dalmazia 11 (1968–70)

Stop 10: Chiesa di San Nicolao della Flue, Via Dalmazia 11 (1968–70)By the late 1960s, Milan was expanding toward its southern peripheries, and new residential quarters required new parish churches to serve rapidly growing populations. The Chiesa di San Nicolao della Flue, commissioned by the Archdiocese of Milan, was built between 1968 and 1970 in the Corvetto district, a working-class neighbourhood undergoing intense urbanization. Unlike Metanopoli’s Sant’Enrico, conceived as part of an industrial utopia, San Nicolao was embedded directly in the city’s fabric, designed to serve a dense, diverse, and evolving urban community.

Gardella approached San Nicolao with his characteristic discipline and sobriety but not without quirks. The church is conceived as a rectangular volume exposed concrete, articulated by a stark yet elegant geometry. The entrance is marked by a modest portico, leading into an interior where light is carefully modulated through vertical slits and skylights. The altar is the focal point, lit from above.

The absence of decorative flourish in the lower box is deliberate, leaving all the expressive power to the higher portion and the roof: Gardella relied on space, proportion, and material to evoke the sacred. His design reflects the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), which emphasized participation, clarity, and community. The church thus stands as both a theological and architectural response to a changing era.

Stop 11: Museo Kartell, Noviglio (Milan HQ), 1967–1972

Stop 11: Museo Kartell, Noviglio (Milan HQ), 1967–1972In the late 1960s, the plastics company Kartell, founded by Giulio Castelli, was emerging as one of the most innovative players in Italian design, pioneering the use of plastics for furniture and household objects. To house its expanding operations, Kartell commissioned Ignazio Gardella to design a new headquarters and factory complex in Noviglio, just outside Milan. Decades later, this same complex became home to the Museo Kartell, one of Italy’s most important corporate museums, dedicated to design history. I had the honour of being project manager to its renovations back in 2015.

The Museum is articulated on several floors through a clever, one-way itinerary.

The Museum is articulated on several floors through a clever, one-way itinerary.The commission was not incidental: Gardella was linked personally and professionally to Anna Castelli Ferrieri, Giulio Castelli’s wife, a key designer at Kartell and one of the most prominent women in post-war Italian architecture and design. Castelli Ferrieri had studied at the Politecnico di Milano, where Gardella taught, and she later collaborated with him on projects. Beyond their professional exchanges, the two shared an intellectual kinship rooted in Milan’s modernist culture. Their dialogue was both professional and personal: Gardella valued her as a designer of equal intellectual stature, and she in turn championed his humanist approach to architecture. The Kartell headquarters embodies this convergence, where industrial functionality is elevated by architectural care, and where design in plastic meets architecture in concrete.

Gardella designed the Kartell headquarters between 1967 and 1972, creating a modular industrial architecture that combined efficiency with clarity. The factory complex was conceived as a series of rational, repetitive volumes, built with reinforced concrete frames and prefabricated panels, reflecting both modern construction methods and the company’s commitment to innovation. You can see its red cladding from the highway and it’s a building very dear to me, due to family ties.

Conclusion: Against Amnesia

Conclusion: Against AmnesiaThis itinerary through Ignazio Gardella’s Milan is not meant to be exhaustive. It is a thread, woven across the city, reminding us that progress does not have to come at the cost of erasure. From the transparent resilience of the PAC to the quiet dignity of the Casa di riposo Biffi, from the housing blocks of Mangiagalli to the solemn austerity of San Nicolao della Flue, Gardella’s work testifies to a simple truth: architecture can innovate while still carrying memory forward.

The demolition of the Padiglione dell’Agricoltura at the old Fiera Campionaria is a wound that makes this walk necessary. It is proof that without vigilance and cultural conscience, Milan always risks sacrificing its own identity in the name of speed and novelty, and it’s been doing so since Ludovico il Moro. To walk Gardella’s city today is to engage in an act of resistance: resistance against forgetting, resistance against speculation disguised as renewal, resistance against the idea that history is an obstacle rather than a foundation.

This resistance is not solitary. The Ordine degli Architetti di Milano has long organised urban walks and itineraries, offering the public the chance to rediscover the city’s layers and contradictions. Joining these initiatives means transforming individual curiosity into shared awareness, cultivating a civic culture where architecture is recognised as a common good.

If Milan is to continue evolving — and it will — it must do so responsibly: with memory as its compass, with curiosity as its method, with innovation as a patient dialogue rather than a rupture. Gardella’s legacy offers a model. It is up to us to walk it, defend it, and carry it forward.