Arousal and Intellect: My Model Reader

It’s all his fault.

A long time ago, I read a book by Umberto Eco called The Limits of Interpretation. But there is a shorter essay on his site that deals with some of the same issues called “The Author and his Interpreters” online. Eco, like many of his generation and those immediately preceding it, had given a lot of thought to the relationship between the writer, the text and the reader. In the latter part of the 20th Century, much more authority was rightly accorded to the reader in the power dynamic of this complex relationship.

And yet still, today, a deep snobbery about what constitutes ‘literature’ remains. If writers can set out to write ‘literary fiction’ and critics can laud it as more ‘important’ than all those novels we consume on airplanes, then has the reader actually gained any authority worth having?

Recently, Ursula K. Le Guin, wrote an outstanding post proposing that any ‘readable’ novel should be considered literature. I would agree with this, but with a bit of a modification. All readable novels aren’t ‘literature’ to every reader. And here, Eco’s excellent concept of shared ‘cultural encyclopedias‘ comes into play. Ian M. Banks’ “The Use of Weapons” is probably not going to be ‘literature’ to someone who has never read any sci-fi before. There needs to be a willingness (a sort of genre-specific suspension of disbelief) to accept a wholly unfamiliar paradigm in order to really have a ‘literary’ experience when reading the book. But if you consider that an examination of violence and its limits a ‘deep’ discussion, then this book is most decidedly deep.

So how could erotic fiction ever be ‘literature’? At the moment, according to most academics, critics and contemporary writers of literary fiction, it can’t. Of course, there are exceptions. It can be considered literature if the author has been dead for a good many years. Apparently only then one can ignore the fact that the text might have any sexually arousing value and concentrate, with adequate seriousness, on the historical context of the work. “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” can be literature because it caused such a social uproar. Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin can be considered literature, because despite the fact that reading it might give you a stiffie, you can contemplate their sexual radicalism within the context of the prevailing social norms of the time. Basically, those books were serious, because they were seriously socially disruptive.

Many people consider Michel Houllebeq to be ‘literary’ because, although he includes repetitive and explicit sex in his novels, it’s all the sort of sex you would rather die celibate than have. I would go so far as to say that, if you found the sex in Houllebeq novels to be arousing, you are probably deeply in need of therapy.

The only type of fiction that can be considered “literary” while courting your libido is gay and lesbian fiction. Admittedly, you’re still not supposed to dwell at any length on how hot the sex scene was, but you can get away with calling it literary because it represents ‘non-heteronormative’ sexuality. And so, very much like D.H. Lawrence in his time, you can proclaim its status as literary by virtue of the fact that, supposedly, its offending someone.

Contemporary heterosexual erotic fiction cannot be considered literature, no matter how loudly you proclaim it to be ‘literary erotica’. You’re simply dressing up smut in lamb’s clothing and putting on airs. It doesn’t matter that your work deals with universally relevant human experiences, or seeks to explore the thornier questions of why people sacrifice amazingly important parts of themselves just to get a leg over. It doesn’t seem to matter that there is an abiding mystery as to why pain and pleasure are so closely related, or how sexual surrender can so closely approximate the erasure of the self.

Critics and academics will all agree that those are worthy subjects worth exploring in literature, as long as you don’t actually describe the act that’s getting us into all this trouble.

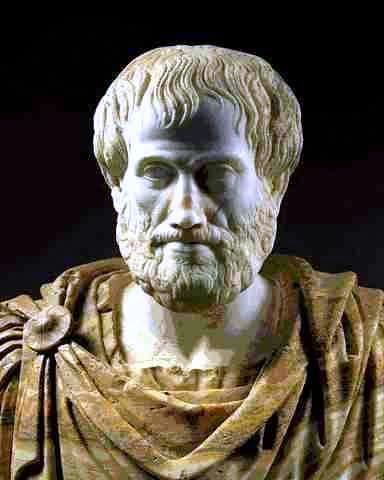

If you happen to read or write erotic fiction, and find all this blythe rejection of the ‘seriousness’ of your genre annoying, you have Aristotle to blame for it.

Yes. Aristotle. The basis upon which it is believed that no text which arouses can be considered serious comes from his Nicomachean Ethics (especially book 7). It was he who proclaimed that sexual arousal / desire / pleasure makes reasoned thinking impossible.

The pleasures are a hindrance to thought, and the more so the more one delights in them, e.g. in sexual pleasure; for no one could think of anything while absorbed in this.

For all we know, he might have meant that a person in the middle of an orgasm can’t think clearly, but this is not how his ideas have been interpreted. Through the centuries and still to this very day, there is a deep rooted belief that sexual desire and rational thought are mutually exclusive. As if sexual desire is a switch – either on or off – and there is no difference between a mild tingling in the groin and full-throttle, blank-brained sexual ecstasy.

Those of us who write and read erotic fiction share a common ‘cultural encyclopedia’. We are well aware that it is possible to be sexually aroused and still capable of critical thought. We are not hormone-addled adolescents. We are perfectly capable and, in certain cases, even find it enjoyable to postpone pleasure. Or be intellectually and sexually stimulated at the same time. Moreover, some of us believe that sexual desire is an integral part of the human experience, and that there is a well of mystery and truth that lies in that experience. Admittedly, it is a landscape of errant and abstract thought, but not a thoughtless place until almost the moment of orgasm.

My modest and less important hypothesis is that erotic fiction can be literature. When well written, it can possess enormous meaning and depth for the adults who read it. It is not produced solely, or even chiefly, for the purpose of aiding masturbation, although it can sometimes have that effect.

We are, contrary to what many critics, academics and readers of ‘literature’ believe, able to find depth in it, enjoy it, and gain insight from it specifically because we are particularly continent readers. We don’t feel the need to pretend that sex or sexual desire doesn’t exist in order to think straight. We’re past the novelty of sex, and on the journey of seeing it within the context of a broader reality.