Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CCXIII–Biophysical Economics

Today’s post is courtesy of a fellow traveller (Schuyler Hupp) on the collapse road that I’ve had the pleasure of communicating with and learning from for a number of years via a mutual Facebook Group (Peak Oil). I present a recent post of his to this Peak Oil FB group directly below, followed by some personal thoughts of mine on the AI response to his query.

CLICK HERE

CLICK HEREIf you’re new to my writing, check out this overview.

I just asked Google Studio AI what problems might be associated with having energy and economic policy makers with little or no science background and along with the written response it provided this illustration.

Here’s the gist of what it regurgitated and rearranged, apparently from biophysical economics literature on the Internet:

“Problems with Policymakers Lacking Science Backgrounds (Operating within the Current Western Economic Paradigm):

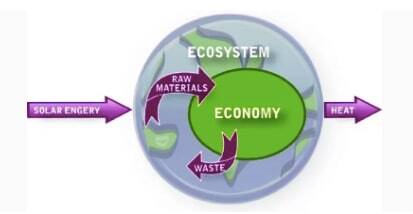

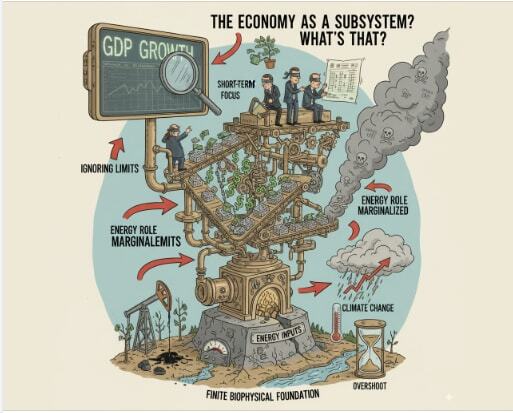

Blind Spot to Biophysical Realities: The current Western economic paradigm largely ignores the foundational role of energy, ecology, and natural capital. Policymakers trained solely in this paradigm tend to view the economy as a self-contained system, divorced from the biophysical world. They fail to understand that economic activity is a subsystem of the ecosphere and thus constrained by its limits.

Short-Termism and Growth Obsession: The prevailing economic model prioritizes short-term GDP growth, marginalizing long-term ecological and resource depletion costs. Policymakers without scientific understanding often see growth as an unalloyed good, even when it drives overshoot and undermines the very natural systems that support human well-being.

Misguided Energy Policies: Without a grasp of energy’s fundamental role, policymakers may underestimate the severity of peak oil or the energy costs of transitioning to renewables. They might push for solutions that are thermodynamically unfeasible or ecologically damaging, or fail to invest adequately in energy efficiency and conservation.

Discounting Future Costs: The economic paradigm often uses high discount rates, making future environmental and resource costs appear insignificant in present-day calculations. This leads to policies that externalize these costs onto future generations.

Belief in Infinite Substitutability and Technological Fixes: A lack of scientific understanding can lead to an unwarranted faith in technological solutions to overcome any resource or environmental constraint, without appreciating the fundamental limits imposed by energy, matter, and the laws of physics. They might believe that “the market will solve it,” even for non-substitutable ecosystem services or critical raw materials.

Vulnerability to Misinformation and Lobbying: Without a solid scientific grounding, policymakers are more susceptible to industry lobbying that downplays environmental risks or exaggerates the costs of regulation, especially when those arguments are presented with a veneer of economic “expertise” that ignores biophysical constraints.

Failure to Adapt to Crisis: As ecological and resource crises intensify due to overshoot, policymakers lacking scientific understanding may react with policies that double down on the very growth-oriented approaches that caused the problems, rather than pursuing fundamental systemic changes.

In essence, placing policymakers without scientific understanding in positions that formulate energy and resource policy is akin to having a financial manager with no understanding of accounting principles trying to run a complex corporation during a period of severe financial distress. They are operating with an incomplete and often fundamentally flawed model of reality, making them ill-equipped to navigate the challenges of the 21st century.”

Schuyler further shared the following with me when I asked about sharing the above:

“…from what I can tell, at least sometimes when you ask AI about economic policy issues, it will regurgitate popular narratives… So you ask it, “What’s the scientific perspective?” or even more specifically, “What is the biophysical economic perspective?”

When I don’t specify science, AI engines will often feed me with popular opinions or “common knowledge” that sounds like ideas that people who are pedigreed in journalism would recycle from the endless circle of uninformed opinion that seems to materialize out of nothing! ”

My thoughts…

My first reaction to the AI response to Schuyler’s query is, ‘of course’. Anyone who views our world in ways that mostly if not completely ignore the biogeophysical realities and limits upon a finite planet can’t help but ‘miss’ some (or all) of the complexities and have a somewhat tainted lens to view the world through. This narrow perspective leads them to believe that they can control many aspects that they in fact cannot via policy and other manipulations–although there exist many scientifically-trained individuals that believe humans can ‘control’ complex systems as well, so perhaps there is no significant difference.

It may be that those without the requisite background knowledge and training in the natural sciences are more likely to have such an impaired perspective. They may see and understand the world in a completely different way than those that are viewing things via a scientific paradigm (which scientific paradigm is also something to consider–a physicist will tend to see the world slightly differently than a biologist or economist or sociologist, for example–and then there’s the entire natural versus social science conundrum).

This being said, I’ve come to understand that many policy-/decision-makers trained in the natural sciences (and even practised it for some time) can and will support and proffer policies that are anything but grounded in ‘good’ science. The reason for this, I believe, is because those with such schooling that tend to get into positions of policy-making and decision-making have spent years within the echo chambers of government and associated institutions; they are, in some sense, no longer practising scientists but politicians and/or bureaucrats that have very different motivations. Those trained in science but with careers in politics/bureaucracies are not necessarily (and perhaps not at all) much better at shutting out the pressures and influences of the established sociopolitical and socioeconomic systems than those not so schooled. In other words, educational training in the natural sciences does not a good policy-maker necessarily make.

It does seem true that most of our ‘elected’ officials and bureaucrats are not well-trained in the natural sciences, if at all. Their schooling tends to be in social sciences or liberal arts (particularly law, economics, and politics) that view the world quite differently than those trained in biology, geology, ecology, physics, etc.. But, again, I’m not sure that those trained in the natural sciences could or would view our social systems and the policies that they are deciding on much differently after a few years or decades immersed in the systems that dominate our societies’ political institutions. [Note: it’s a very different conversation if one is in an ‘advisory’ role where there is no decision and policy making; my experience in such situations is that the policy that is implemented almost always reflects the sociopolitical and/or socioeconomic status quo–discussions and concerns voiced in advisory committees are rarely truly influential in institutional policy; and that was my personal experience for a few school board-level ones that I sat on as a teacher federation representative within the field of education.]

I’ve also witnessed a number of people in political positions acknowledge the negative consequences of our pursuit of perpetual growth on a finite planet (particularly the environmental impacts) yet support wholeheartedly continued growth. Such acknowledgements may be merely theatrical in nature, but their typical rebuttal is something along the lines of ‘It’s different this time because we can do it better/smarter’ or ‘We don’t want to avoid the good at the expense of pursuing the perfect’ or ‘We’re putting a butterfly parkette in to compensate for the wetlands and forest being paved over for the homes and roads’. These responses, to me, are rationalisations to continue with status quo policies. And most politicians/bureaucrats regardless of educational training go along with such things to avoid ‘rocking the boat’ and/or ensure continued advancement within the institutions in which they are employed.

I am not, therefore, convinced at all that putting those with a science background in positions of policy- and decision-making would change things much, if at all. It might work, in theory, but there’s often if not always a disconnect between theory and practice.

And then, of course, there’s the entire notion that we have little to no agency in changing the course our species seems to be on…or that ecological overshoot is a predicament that can at best be mitigated marginally and certainly not ‘solved’ via policy…or that our species’ problem-solving behaviour tends to exacerbate the issues that we are attempting to address…or that complex systems with their nonlinear feedback loops and emergent phenomena tend to react to perturbations (including human interventions) in completely unexpected, unpredictable, and uncontrollable ways.

Perhaps the issue here is not who is ‘in charge’ and their educational background but some deeper flaw in our species and its means of adaptation to an uncertain universe…

Thank you, Schuyler, for once again giving me something to ponder today as I spent a few hours in my food gardens harvesting some late-maturing veggies and preparing the beds for the coming Canadian winter…

What is going to be my standard WARNING/ADVICE going forward and that I have reiterated in various ways before this:

“Only time will tell how this all unfolds but there’s nothing wrong with preparing for the worst by ‘collapsing now to avoid the rush’ and pursuing self-sufficiency. By this I mean removing as many dependencies on the Matrix as is possible and making do, locally. And if one can do this without negative impacts upon our fragile ecosystems or do so while creating more resilient ecosystems, all the better.

Building community (maybe even just household) resilience to as high a level as possible seems prudent given the uncertainties of an unpredictable future. There’s no guarantee it will ensure ‘recovery’ after a significant societal stressor/shock but it should increase the probability of it and that, perhaps, is all we can ‘hope’ for from its pursuit.”

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies: see here.