Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CCXII–A ‘Great Simplification’ Is On Our Doorstep, Redux

A couple of months ago, I penned an article summarising a handful of resources that had helped to inform and guide my thinking on our various predicaments. Those five resources were just a sampling of the ones I’ve been exposed to over the years. During my initial exposure to the concept of peak oil and its implications for societal collapse, I devoured numerous resources as I struggled to understand the information and process the arguments being made.

Below you will find another half dozen summaries of additional resources I reviewed with an attempt to combine their arguments into a coherent ‘conclusion’ about what they suggest for humanity’s future….which is not unlike that reached in the first post. (see: Website Medium Substack)

Collapse

The 2009 documentary, Collapse, features the late Michael Ruppert and was the driving force for my journey into the rabbit hole of peak oil and a revisiting and deeper look into the idea of societal ‘collapse–I bought and read Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse Of Complex Societies not long after viewing the documentary.

I was somewhat aware of the notion of societal decline, having pursued an undergraduate degree and Master of Arts in anthropology (focussing mostly on North American archaeology; working on archaeological digs in Ontario, Canada, and near Oaxaca, Mexico), but never truly read much on it or its wider implications while a student–except for reading Bruce Trigger’s Times and Traditions: Essays In Archaeological Interpretation that, amongst other things, explored the notion of cultural continuity over time (I worked for/with and learned from two of his graduate students–one that remained in academia, Dr. David G. Smith). And I had never heard the term ‘Peak Oil’ prior to watching this documentary.

One fateful Friday evening in late 2010, on a family outing to our local Blockbuster to pick up some videotapes for weekend viewing, I came across Collapse and it sounded interesting. So, I rented it to watch sometime in the next few days–along with some others (probably a Pixar movie or two given the age of my daughters at the time), likely the latest Toy Story or The Incredibles.

The documentary is basically an extended interview with Michael Ruppert, a Los Angeles narcotics detective turned whistleblower, journalist, and author. While the director of the film was seeking Ruppert out to follow-up on his accusations about high-level drug smuggling by the CIA, he found Ruppert had become far more interested in the concept of Peak Oil, our debt-based and financialised economic system, government and corporate malfeasance, environmental degradation, and the implications of all of these for industrial civilisation and its sustainability.

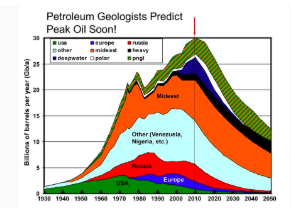

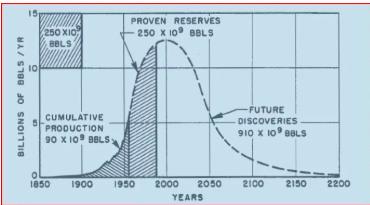

forbes.comThe primary concern raised by Ruppert in the documentary is the peak of hydrocarbon resources, particularly oil. He argues that it is a key tipping point for societal collapse given the importance of this resource for maintaining virtually every complex system in modern societies–particularly manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture. He also stresses that oil is vital for sustaining the growth that underpins our monetary systems and financialised economies. He asserts that the decline of cheap, abundant oil means the decline of the energy available to keep our modern, global-industrial societies functioning, and certainly not growing as they have.

Ruppert goes on to argue that the much ballyhooed and trumpeted alternatives (i.e., nuclear, solar, biofuels, wind, hydrogen) cannot replace oil’s density nor its scale, being distractions or worse (i.e., scams). He is also highly critical of the Ponzi-type structure of our debt-based financial system and its dependence upon infinite growth on a finite planet. He argues that this is an entirely unsustainable system and is set up for a catastrophic collapse at some point.

Ruppert also points out that there is an awareness of the above converging crises by the world’s governments and corporations, and that they are covering them up in order to suppress dissent and maintain status quo economic and power structures. It was Ruppert’s growing awareness and investigations into CIA drug trafficking that opened his eyes to the systemic corruption prevalent in government and eventually led him to appreciating how important energy resources are to supporting industrial civilisation–a significant amount of government policy and action has been oriented towards securing and controlling energy (i.e., oil) reserves, regardless of the ‘costs’.

Ruppert highlights the undeniable fact that humanity has entered ecological overshoot by living far beyond the planet’s natural environmental carrying capacity through its consumption of resources in a manner significantly faster than they can be replenished. His contention is that modern, industrial civilisation founded upon cheap oil (and other hydrocarbons) and with a completely unsustainable economic system is on the precipice of ‘collapse’ with no ‘solutions’ to this predicament.

You can view this documentary here.

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality

Ecologist Richard Heinberg’s 2011 text asserts that the exponential economic growth that has been present since the Industrial Revolution has basically ended due to fundamental biogeophysical limits. This, he argues, is a permanent decline and not a temporary phenomenon.

He posits that this cessation is due to: energy constraints (particularly easy- and cheap-to-access hydrocarbons); ecological systems degradation (most planetary boundaries have been breached–especially with respect to resource scarcity, biodiversity loss, pollution, and climate); and, economic instability (due to its debt-based foundation and the need for perpetual growth to sustain it).

resilience.orgHeinberg further challenges the concept of growth being synonymous with prosperity, stressing that the negative social and environmental costs are typically ignored. He contends that the growth imperative that societies pursue is completely unsustainable on a finite planet, and that the depletion of resources and falling net energy are limits that economic analyses overlook. He also argues that the technology and economic ‘solutions’ typically chased can only provide temporary relief, being unable to replace hydrocarbons at scale or energy density.

He believes that there is no immediate threat but that the growth we have known has ended and we have a choice to make between unmanaged ‘collapse’ and ‘managed’ decline towards a ‘steady-state’ economy that exists within ecological boundaries.

The components of his proposed response with respect to managing societal ‘degrowth’ include, in no particular order, efforts to: stabilise population growth in order to reduce increasing demand and stress on the planet; reduce consumption and waste, thereby conserving resources; relocalise economies to reduce dependence upon fragile, long-distance supply chains; abandon our debt-based monetary system and its dependence upon perpetual growth, and restructure/write-down current, unpayable debts; rapiding scale up ‘renewable’ energy sources; and, encourage sufficiency, sustainability, and community, while discouraging material accumulation.

Heinberg’s contention is that the 2008 financial crisis was not a one-off, isolated event but a symptom of deeper systemic limits to growth, and stresses the consequences of energy depletion on the financial system. He suggests that fundamental change to the system is necessary given the long-term prospects of continuing the growth imperative.

Basically, Heinberg presents the argument that the global economy has encountered a limit with significant headwinds caused by debt saturation, resource depletion, and environmental degradation. He concludes that disaster is guaranteed if we continue with the growth paradigm and that the best path forward is a conscious transition towards resilient communities and an ecologically-sustainable economy.

The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future Of Our Economy, Energy, And Environment

Chris Martenson’s The Crash Course (2011) suggests that the next twenty years are going to be very different from the past twenty as three converging crises (i.e., energy, economy, environment) are increasingly impacting humanity and its modern societies. Martenson argues that our various systems are unsustainable and set up for a ‘crash/collapse’, primarily due to our exponential growth (population and economic) bumping into the biogeophysical limits of a finite planet.

The most fundamental issue, according to Martenson, is humanity’s poor understanding of the exponential function and our pursuit of growth. This is especially true as it pertains to population, debt, resource consumption, and the impacts of these on the environment. While things can appear stable for a long period of time, exponential growth results in dramatic, sudden consequences.

shutterstock.comOf primary importance are the interlocking crises of the three Es: economy, energy, and the environment.

The current world economy has been founded upon ever-increasing debt (particularly since the gold-standard was abandoned) with a money system requiring continuous growth to avoid collapse. Massive unfunded liabilities are present (that likely won’t be met) along with destabilising inequality.

Our current societies depend upon energy for all its complex systems, particularly that derived from hydrocarbons. We have enjoyed more than a century of cheap, high-quality, and abundant hydrocarbons (especially oil) to build modernity, but that time has passed with the more expensive, more difficult to extract, and lower EROEI (energy-return-on-energy-invested) hydrocarbons now dominant. Given our dependency on this resource (and alternative’s inability to scale up, their intermittency, and increasing mineral/material challenges), the growth needed to keep our complexities functioning is at risk.

Not only is the exponential growth humanity is pursuing colliding with resource limits, but climate change has become a major threat along with pollution and degradation of our environment. These things are putting the planet’s ability to support human economic activity and all life at risk.

Martenson emphasises that these crises are interrelated in a complex manner with economic growth requiring energy, but the extraction and use of energy is resulting in ecological systems disruption and collapse. This environmental harm negatively impacts the economy with increasing amounts of energy necessary to mitigate the negative consequences. But debt-based money needs growth, requiring even more resources and energy–a very problematic feedback loop.

This pursuit of perpetual growth on a planet with finite resources is impossible and so the system will change, regardless of our wishes to sustain it. This ‘crash’ is a process, not an event, and will result in a lower-throughput world. We are likely to experience a long period of economic contraction, resource scarcity, environmental instability, and social disruptions.

Martenson offers some means of adapting on various levels. On a personal level, he suggests getting out of debt and putting any savings in tangible assets, learning some practical skills, and building local connections. For communities, he believes that they should build local food systems and economic networks, and create local energy production. Finally, on a societal level, he argues that there should be a proactive transition towards true sustainability. In particular, Martenson includes an entire chapter (What Should I Do?) on actionable advice, such as preparedness, personal finance, and community building.

This text outlines the systemic risks for modernity, highlighting the interlocking complexity of the environment, economy, and energy, and why the pursuit of perpetual growth on a finite planet is a dangerous myth. As a result, Martension stresses that humanity should begin immediate preparation by way of adopting adaptive strategies that provide communities with resilience.

You can access the video series of this text here.

The Long Emergency: Surviving the Converging Crises of the Twenty-First Century

James Howard Kunstler’s The Long Emergency (2005) presents the case that our modern world, built upon relatively inexpensive hydrocarbons (particularly oil), has begun an era of building crises and contraction. As a result of ‘Peak Oil’ a decades-long period of resource scarcity, economic contraction, social disruptions, and environmental degradation is upon us. This will result in the eventual collapse of modernity’s complex systems and a return to localised, agrarian communities.

Of particular importance to these crises is Peak Oil–the peak of the easy-to-access conventional oil is the ultimate catalyst to our predicament. With its portability, energy-denseness, and importance to virtually everything in our societies (especially agriculture, transportation, and manufacturing), its decline equals the contraction of human economies and interconnectedness.

The failure of ‘renewables’ to be able to be scaled up in time or be as effective to alleviate the eventual depletion of oil puts the continuation of modernity at significant risk. This risk is being exacerbated by a changing climate that is contributing to drought, floods, agricultural disruptions, and infrastructure damage and destruction.

But even with ‘renewables’, the issue of resource depletion is becoming problematic with shortages of fresh water, fish, topsoil, and various important minerals. On top of these issues is the rise of infectious disease and the likelihood of pandemics that can result in population displacement, antibiotic resistance, supply chain disruptions, etc..

As these predicaments combine to add increasing stress to our world, we are witnessing growing economic and political instability. Kunstler predicts the failure of centralised governments and our globalised and financialised economic systems as a result of this, leading to increased authoritarianism, international and domestic fragmentation, and conflict.

He further suggests that our world will soon witness the: ‘collapse of suburbia’ (“the greatest misallocation of resources in history”) due to its significant dependence upon cheap oil (e.g., cars and trucks), lack of local resources, and inefficient land use; end of globalisation as complex and fragile long-distance supply chains falter, alongside the growth of localised/regional economies; contraction of our finance-based and growth-dependent global economies; decline of populations because of famine, disease, and conflict; sociopolitical stress and extremism, accompanied by social unrest, mass migrations, and rising conflict over resources due to shortages; rise of ‘Agrarian Localism’ signalled by labour-intensive farming communities where skills and knowledge in farming, carpentry, and small engines will be vital to community survival. All of this will lead to geographic-based winners and losers where areas with potable water, fertile soil, and navigable waterways will fare much better than those without.

The book is a warning that the abundance of modernity (at least for some in so-called advanced economies) is approaching an end with the waning of inexpensive oil. Kunstler predicts an at-times chaotic restructuring of human societies and calls for a recognition of the ever-present risks of our globalised, industrial-based world and for building community-level resilience.

The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age

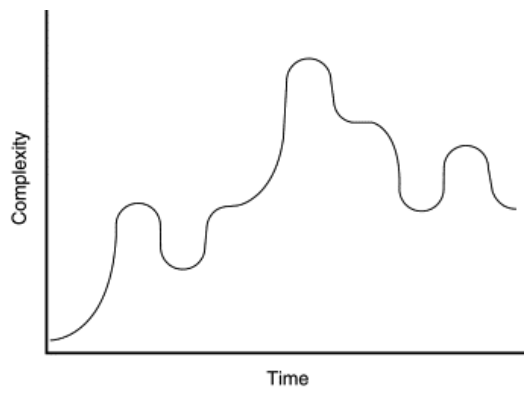

John Michael Greer’s 2008 text presents the case that industrial civilisation’s simplification will be a rather long and uneven decline by way of what he terms ‘Catabolic Collapse’. There will be long periods of stability with relatively shorter periods of crisis—a staircase-type descent over generations towards a deindustrialised future.

The idea of ‘catabolic collapse’ is based on the notion that a society will consume its capital (e.g., infrastructure, social complexity) to meet the needs that erupt during a crisis, similar to an organism cannibalising its body for energy when starving. When a crisis arises, such as an economic depression, breakdown and loss occurs but stabilisation at a lower level of complexity eventually takes place based upon use of ‘resources’ from the previous, higher level. This ‘cycle’ occurs periodically over decades/centuries leading to a much simplified society/civilisation with variability depending upon local context.

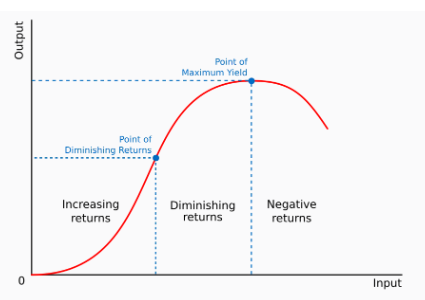

The impossibility of pursuing perpetual growth on a finite planet combined with diminishing returns on investments in complexity are the prime causes of ‘collapse’. Resource depletion (especially of oil), environmental damage, and economic instability have led to this irreversible predicament with the rate of decline and the challenges encountered varying widely depending upon regional context and the resources available.

Greer stresses that there will be significant sociocultural and psychological challenges to this descent, especially as it pertains to beliefs in progress and privilege. He is quite critical of the blind faith most have regarding technology and its ability to ‘save’ humanity from this predicament, especially because they all depend upon the resources that are quickly depleting and/or they almost always create new issues/problems.

Greer’s advice for addressing the issues is for individuals and communities to try and avoid the denial of this reality and build local resilience via practical skill development (e.g., traditional crafts, gardening, basic healthcare, etc.) to reduce as much as possible reliance upon the complexities of modern societies. He sees the attempts to save our industrialised societies as futile and argues that we would be better to learn how to repurpose equipment and preserve valuable knowledge and skills that will serve regions in a de-industrialised world.

Greer’s perspective is based upon pre/historical examples of ‘collapse’, ecology, and systems thinking. It focuses upon practical adaptation rather than attempts to maintain the unsustainable, arguing that the future will not be characterised by either the utopian nor apocalyptic predictions. The future will be one of a lengthy, descending staircase due to ecological limits and resource depletion. Its multi-generational descent affords the opportunity to those willing to accept its inevitability the time to prepare for a more localised and hopefully sustainable future.

[See: Today’s Contemplation: Collapse Cometh CXXXV–Collapse Now To Avoid The Rush: Our Long Emergency. Website Medium Substack]

The End of Growth: Adapting to a New Reality of Expensive Oil and Slower Growth

Economist Jeff Rubin’s 2012 text argues that high, sustained oil prices (due to geopolitical instability and scarcity) have brought an end to the ongoing economic growth of the past century. These high oil prices act as a ‘tax’ by increasing production costs across all sectors and typically trigger recessions. Rubin predicts that a permanent high price could prevent a robust recovery towards previous growth rates.

Moreover, inexpensive transportation fuels are what has aided the growth of globalisation, long-distance supply chains, and just-in-time delivery/inventory systems; higher prices put these all at risk. We should expect a relocalisation of production as a result; alongside more expensive consumer products.

Unconventional oil resources (i.e., shale and bitumen/tar sands) are not the saviours they are being touted as since they are far more expensive to extract. They will not bring lower costs back, nor result in the surplus net energy that sustains growth. Alternatives such as complex wind and solar technologies are also not helpful since they are expensive and cannot scale up rapidly. These ‘renewables’ require massive investments that are more difficult to make in an era of low growth and high debt.

Rubin argues that recessions and the debt crises and austerity that tend to follow are the symptoms of expensive energy and not the cause. The fallout from increasing energy prices are feedbacks that further depress demand and result in slower or stagnant economic growth and price inflation (i.e., stagflation).

With higher energy prices, we are likely to experience what Rubin terms ‘stagflation lite’ characterised by much slower growth and persistent price inflation. Central banks that are charged with stimulating growth (usually via attempts to reduce interest rates) while fighting price inflation (usually via attempts to increase interest rates) are caught in a dilemma.

Rubin predicts that consumers in ‘developed’ economies will experience a decline in their consumption due to price inflation caused by higher energy prices. There will also be a continued shrinking of the ‘middle’ class, and reduced trade deficits and volume for these economies. He further believes that expensive fuels will reduce long-distance commuting, making suburban communities less attractive and leading to a revitalisation of urban centres. There will also likely be a resurgence of local and regional goods production, especially of food.

As an economist, Rubin focuses mostly upon the price of oil and its knock-on impacts. He holds that this is the most important aspect and not resource depletion per se. He notes the historical connection between recessions and oil price spikes. Rubin considers the end of growth as an economic inevitability driven by market forces but not necessarily resulting in ‘collapse’.

Basically, he argues that the era of relatively cheap oil has ended and with it the end of the robust growth developed economies have experienced for decades. The hyper-globalisation characterised by this time will reverse and a relocalisation of goods production will ensue. This transition will see slower growth, higher prices, and a lower standard of living, particularly in terms of material goods.

These resources come to a relatively common conclusion: over the coming decades modern human societies will experience an inevitable transformation due to fundamental constraints and significant challenges.

Primary among their messages is that the growth human societies have experienced for some centuries (and especially the past two, thanks to cheap and abundant hydrocarbons) is approaching an inescapable end. Environmental degradation, the limits imposed by finite resources, and an unsustainable debt-based financial system have combined to bring a rather abrupt halt to the ongoing growth of humanity, particularly its population and economies. Founded upon the idea of perpetual growth, modern complex societies cannot continue on their current trajectory. A significant reduction in material throughput is guaranteed which can’t help but lead to economic stagnation/collapse.

The primary reason for all of this is that the relatively dense energy resource that has been easy-to-access and cheap-to-extract/-distribute–and enabled modernity (in the sense of industrialisation and massive, globalised energy-averaging systems)–has encountered significant diminishing returns. The consequence of this is that less and less net energy is available as time passes, and is made worse by our growth momentum. While some argue that alternative energy sources are important to pursue, they admit that they are insufficient to maintain societal complexity.

Given the above, it seems certain that the future of human societies will be one with far less energy available leading to far less complexity. This means the contraction and eventual loss of most long-distance supply chains, with more localised production of goods. The organisational and technological complexity of modernity will also contract and simplify, meaning less bureaucracy and much greater reliance on local knowledge/skills, manual labour, and simpler tools. Regions with ample local resources (especially water and arable lands) may fare relatively well but large urban centres that depend upon the inflow of resources will very likely struggle.

It’s important to note that while there may be very turbulent periods during this inevitable contraction, most authors contend that the coming simplification will be relatively gradual. ‘Collapse’ will not likely be ‘sudden’ but will be prolonged with periods of crises as well as periods of relative stability, and perhaps even some ‘recovery’ to a higher level of complexity–at least for a short time before continuing its simplification.

The consequences of the coming simplification will probably be uneven for regions, communities, and social classes. Much will depend upon local resources, infrastructure, leadership, and social cohesion. There is likely to be much turmoil, instability, and conflict. Societies are likely to experience resource conflict, political uncertainty, economic recession/depression, social discontent, and quite possibly violence. Many also suggest that climate change will act as a ‘threat multiplier’.

Overall, these individuals contend that extinction is not the likely outcome but a radical transformation of our global, industrialised societies is since these are quite unsustainable. The inevitable simplification/descent/collapse/decline of complex societies will likely experience bouts of drastic disruption and conflict, as well as severe hardships and increasing vulnerability to shocks (e.g., political, economic). Community/regional resilience via social cohesion, practical skills, local resources, etc., will aid in adapting to changes as they occur over decades/generations.

While the future is certainly uncertain, prospects strongly suggest it will be one of less complexity and energy, and one of increasing localisation. The speed of energy decline, climate impacts, and adaptive effectiveness will determine the path and severity of the trajectory for most.

Prepare accordingly.

What is going to be my standard WARNING/ADVICE going forward and that I have reiterated in various ways before this:

“Only time will tell how this all unfolds but there’s nothing wrong with preparing for the worst by ‘collapsing now to avoid the rush’ and pursuing self-sufficiency. By this I mean removing as many dependencies on the Matrix as is possible and making do, locally. And if one can do this without negative impacts upon our fragile ecosystems or do so while creating more resilient ecosystems, all the better.

Building community (maybe even just household) resilience to as high a level as possible seems prudent given the uncertainties of an unpredictable future. There’s no guarantee it will ensure ‘recovery’ after a significant societal stressor/shock but it should increase the probability of it and that, perhaps, is all we can ‘hope’ for from its pursuit.”

If you have arrived here and get something out of my writing, please consider ordering the trilogy of my ‘fictional’ novel series, Olduvai (PDF files; only $9.99 Canadian), via my website or the link below — the ‘profits’ of which help me to keep my internet presence alive and first book available in print (and is available via various online retailers).

Attempting a new payment system as I am contemplating shutting down my site in the future (given the ever-increasing costs to keep it running).

If you are interested in purchasing any of the 3 books individually or the trilogy, please try the link below indicating which book(s) you are purchasing.

Costs (Canadian dollars):

Book 1: $2.99

Book 2: $3.89

Book 3: $3.89

Trilogy: $9.99

Feel free to throw in a ‘tip’ on top of the base cost if you wish; perhaps by paying in U.S. dollars instead of Canadian. Every few cents/dollars helps…

https://paypal.me/olduvaitrilogy?country.x=CA&locale.x=en_US

If you do not hear from me within 48 hours or you are having trouble with the system, please email me: olduvaitrilogy@gmail.com.

You can also find a variety of resources, particularly my summary notes for a handful of texts, especially William Catton’s Overshoot and Joseph Tainter’s Collapse of Complex Societies: see here.