Queen of Bohemia: A Q & A with Eve Kahn

I’m delighted to have Eve Kahn back on the Margins to talk about her new book, Queen of Bohemia Predicts Own Death: Gilded Age Journalist Zoe Anderson Norris. Queen of Bohemia is the story of a Kentucky-born belle turned ferocious New York journalist who used her pen to advocate for impoverished immigrants and to expose corrupt politicians. (I leave you to make any comparisons you please.) Eve—and Zoe—give us a different image of the Gilded Age. I was hooked from page one.

Take it away, Eve!

Even well-known women in the nineteenth century are often neglected by biographers and historians. What path led you to the story of journalist Zoe Anderson Norris, and why do you think it’s important to tell her story today?

I was introduced to Zoe (as everyone called her) in 2018 by my friend Dr. Steven Lomazow, a neurologist and preeminent historian of American magazines—his holdings of some 83,000 periodicals date back to the 1700s and include examples of Zoe’s groundbreaking bimonthly magazine, The East Side (1909-1914). I could not believe, in 2018, that no scholar had written anything about this expectation-defying woman. She set out “to fight for the poor with my pen,” and her self-published writings combating bigotry against immigrants resonate in our own tumultuous times. She documented, for instance, the sufferings of sweatshop workers at firetraps including the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory—like my own Ukrainian-born ancestors—and caged deportees at Ellis Island.

Zoe was a well-known journalist and activist during her lifetime, but is largely forgotten today. Why do you think stories like hers vanish from history?

History so often gets told because of flukes, for instance someone’s papers land at the right institutions and are findable by scholars. Zoe’s descendants in her sleepy Kentucky hometown tucked away a boxful of her manuscripts and memorabilia. Who knows what would have been previously published about Zoe if, perhaps, she’d corresponded copiously with someone celebrated like Willa Cather and those letters survived in some well-combed archive?

Zoe sometimes went undercover for her stories about immigrant poverty. How does Zoe fit into the tradition of “stunt girl” journalists?

It’s fascinating that Zoe never, as far as I know, wrote about those newspaperwomen, her trailblazer predecessors and colleagues like Nellie Bly. And Zoe’s take on undercover reporting is wry and self-deprecating, it’s sui generis. She sometimes made fun of herself for being poorly disguised. She wrapped herself in shawls while pretending to be an immigrant accordionist beggar, taking notes on wealthy philanthropists ignoring her while other beggars gave her coins, but one of the few songs she could play, “My Old Kentucky Home,” was a dead giveaway of her Kentucky origins.

The Gilded Age has been a popular history hotspot for several years now, the setting for the television series by that name, now at the end of its third season, and a number of best-selling novels, including The Personal Librarian, The Address, and The Social Graces. In your subtitle, you describe Zoe as a Gilded Age journalist. How does her story relate to the world evoked in such works?

I’ve had many conversations about this, especially with my podcaster friend Carl Raymond, “The Gilded Gentleman.” Zoe wrote vividly about her era’s gaping disparities and fluidity. Immigrants were starving and freezing on garbage-strewn streets, a few blocks from new skyscrapers “flashing back the fire of the sun” (Zoe’s gorgeous phrase) and liveried servants hoisting bejeweled blueblood employers into carriages upholstered in velvet. And yet immigrants were also visibly getting footholds in a new land, elbowing their way from wheeling pushcarts to running department stores.

Writing about a historical figure like Zoe Anderson Norris requires living with them over a period of years. What was it like to have her as your constant companion?

You can’t believe how often I see the world through Zoe’s eyes. Just the other day I was heading back to Manhattan across an East River bridge and I thought, oh, there are those luminous skyscrapers still flashing back the fire of the sun, in a town still so full of gaping economic disparities and fluidity.

Can you tell me where you got the title Queen of Bohemia?

Zoe drew people into her social justice battles and attracted new East Side subscribers by having fun, especially at weekly restaurant dinners for an intentionally disorganized bohemian group that she organized, the Ragged Edge Klub. Reporters descended on Klub meetings as the members tried out trendy ragtime dance moves, like the Tarpon Squirm and Banana Peel Slide (that one required wearing white tights under a yellow gown). Newspapers dubbed Zoe the Queen of Bohemia, and at first she chafed at that title, since bohemia in her time suggested a place full of unbathed, self-indulgent wastrels. But eventually she ironically coronated herself, and she used a wine bottle as a scepter to anoint her friends with aristocratic titles—Baron Bernhardt of Hoboken, for instance, and Lady Betty Rogers of the Bronx.

Zoe is not a major historical figure. How difficult is it to find sources for women whose lives are not well documented? What is your favorite research tip for people who want to write about relatively obscure historical women?

Any institution that seems, as you comb through databases like worldcat.org and ArchiveGrid, to have anything related to someone who knew the figure you’re researching, don’t hesitate to call or email the librarians for deeper dives into the finding aids and boxes. And don’t hesitate to call or email people descended from people you’re researching. You can’t imagine how often, even in this age of constant downsizing and tossing out heirlooms, I reach someone who says, basically, “oh, call my sister, she’s the keeper of family stories and artifacts, she’s got a box in the garage.”

What was the most surprising thing you learned working on this book?

How many descendants of people whose lives Zoe touched remembered her as the Queen of Bohemia, who fought for the poor with her pen. How amazing that the daughter and granddaughter of The East Side’s illustrator William Oberhardt carefully kept mounds of his sketched portraits of immigrants (which the family donated, bless them, to the New York Historical). And how amazing that Zoe’s descendants include writers and social justice advocates.

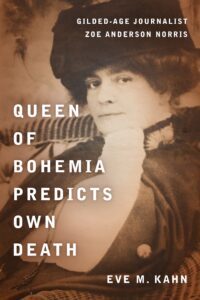

Independent scholar Eve M. Kahn’s Queen of Bohemia Predicts Own Death: Gilded-Age Journalist Zoe Anderson Norris (Fordham U. Press) has been called “a daring story told with exceptional verve” (Amy Reading, 2024 Pulitzer finalist and biographer of New Yorker editor Katharine White). Kahn writes for The New York Times (where she served as weekly Antiques columnist, 2008-2016), among other publications. Her 2019 biography of the Connecticut-born, globetrotting painter Mary Rogers Williams (1857-1907) from Wesleyan University Press won awards from institutions including the Connecticut League of History Organizations.