How the Ancients Coped with Grief, Loss, and Bereavement

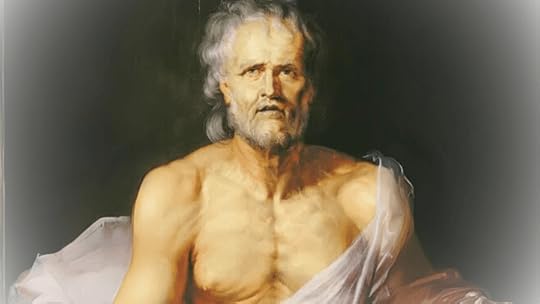

The Stoic Seneca is the master of the ‘consolation’, a letter written for the express purpose of comforting someone who has been bereaved. Seneca wrote at least three consolations, to Marcia, to Polybius, and to Helvia. In the Consolation to Helvia, he comforts his own mother Helvia on ‘losing’ him to exile—an unusual case, and literary innovation, of the lamented consoling the lamenter.

The emperor Marcus Aurelius (d. 180 CE) had at least fourteen children with his wife Faustina, but only four daughters and one unfortunate son, Commodus, outlived their parents. In the Meditations, Marcus likens his children to leaves, and paraphrases Homer in the Iliad:

Men come and go as leaves year by year upon the trees. Those of autumn the wind sheds upon the ground, but when the spring returns the forest buds forth with fresh vines.

Marcus was a Stoic, and would have known, at least in principle, how to cope with grief, loss, and bereavement. But if Seneca could have consoled Marcus on the loss of his children, and could only have told him three things, what might those three things have been?

First, Marcus, remember that life is given to us with death as a precondition. Some people die sooner than others, but life, on a cosmic scale, is so short that, really, it makes no difference. Even children are known to die—indeed, they often do—and these, Marcus, simply happened to be your own. A human life, however long or short, or great or small, is of little historical and no cosmic consequence. Since a life can never be long or great enough, the most that it can be is sufficient, and we would do better to concentrate on what that might mean.

Second, it may be that death is in fact preferable to life (the secret of Silenus). Life is full of suffering, and grieving only adds to it, whereas death is the permanent release from every possible pain. Indeed, many people who have died—think only of our friend Cicero—would have died happier if they had died sooner. If we do not pity the unborn, why should we pity the dead, who at least had the benefit, if benefit it is, of having existed? The unborn cry out as soon as they are delivered into the world, but to the dead we never have to block our ears. If weep we must, it is not over death, but the whole of life, that we should weep.

Third, we should treat the people we love not as permanent possessions but as temporary loans from fortune. When, in the evening, you kiss your wife and children goodnight, reflect on the possibility that they, and you, might never wake up. In the morning when you kiss them goodbye, reflect on the possibility that they, or you, might never come home. That way you’ll be better prepared for their eventual loss, and, what’s more, savour and sublime whatever time that you have with them—and, in that way, lead them to love you more.

If you do lose a loved one, do not grieve, or no more than is appropriate, or no more than they would have wanted you to, but be grateful for the moments that you shared, and consider how much poorer your life would have been if they had never come into it.

The post How the Ancients Coped with Grief, Loss, and Bereavement appeared first on Neel Burton author website and bookshop.