The problems that accountability can’t fix

Accountability is a mechanism that achieves better outcomes by aligning incentives, in particular, negative ones. Specifically: if you do a bad thing, or fail to do a good thing, under your sphere of control, then bad things will happen to you. I recently saw several LinkedIn posts that referenced the U.S. Coast Guard report on the OceanGate experimental submarine implosion. These posts described how this incident highlights the importance of accountability in leadership. And, indeed, the report itself references accountability five times.

However, I think this incident is an example of a type of problem where accountability doesn’t actually help. Here I want to talk about two classes of problems where accountability is a poor solution to addressing the problem, where the OceanGate accident falls into the second class.

Coordination challengesManaging a large organization is challenging. Accountability is a popular tool in such organizations to ensure that work actually gets done, by identifying someone who is designated as the stuckee for ensuring that a particular task or project gets completed. I’ll call this top-down accountability. This kind of accountability is sometimes referred to, unpleasantly, as the “one throat to choke” model.

Darth Vader enforcing accountability

Darth Vader enforcing accountabilityFor this model to work, the problem you’re trying to solve needs to be addressable by the individual that is being held accountable for it. Where I’ve seen this model fall down is in post-incident work. As I’ve written about previously, I’m a believer in the resilience engineering model of complex systems failures, where incidents arise due to unexpected interactions between components. These are coordination problems, where the problems don’t live in one specific component, but, rather, how the components interact with each other.

But this model of accountability demands that we identify an individual to own the relevant follow-up incident work. And so it creates an incentive to always identify a root cause service, which is owned by the root cause team, who are then held accountable for addressing the issue.

Now, just because you have a coordination problem, that doesn’t mean that you don’t need an individual to own driving the reliability improvements around it. In fact, that’s why technical project managers (known as TPMs) exist. They act as the accountable individuals for efforts that require coordination across multiple teams, and every large tech organization that I know of employs TPMs. The problem I’m highlighting here, such as in the case of incidents, is that accountability is applied as a solution without recognizing that the problem revealed by the incident is a coordination problem.

You can’t solve a coordination problem by identifying one of the agents involved in the coordination and making them accountable. You need someone who is well-positioned in the organization, recognizes the nature of the problem, and has the necessary skills to be the one who is accountable.

Miscalibrated risk modelsThe other way people talk about accountability is about holding leaders such as politicians and corporate executives responsible for their actions, where there are explicit consequences for them acting irresponsibly, including actions such as corruption, or taking dangerous risks with the people and resources that have been entrusted to them. I’ll call this bottom-up accountability.

The bottom-up accountability enforcement tool of choice in France, circa 1792

The bottom-up accountability enforcement tool of choice in France, circa 1792This brings us back to the OceanGate accident of June 18, 2023. In this accident, the TITAN submersible imploded, killing everyone aboard. One of the crewmembers who died was Stockton Rush, who was both pilot of the vessel and CEO of OceanGate.

The report is a scathing indictment of Rush. In particular, it criticizes how he sacrificed safety for his business goals, ran an organization that lacked that the expertise required to engineer experimental submersibles, promoted a toxic workplace culture that suppressed signs of trouble instead of addressing them, and centralized all authority in himself.

However, one thing we can say about Rush was that he was maximally accountable. After all, he was both CEO and pilot. He believed so much that TITAN was safe that he literally put his life on the line. As Nassim Taleb would put it, he had skin in the game. And yet, despite this accountability, he still took irresponsible risks, which led to disaster.

By being the pilot, Rush personally accepted the risks. But his actual understanding of the risk, his model of risk, was fundamentally incorrect. It was wrong, dangerously so.

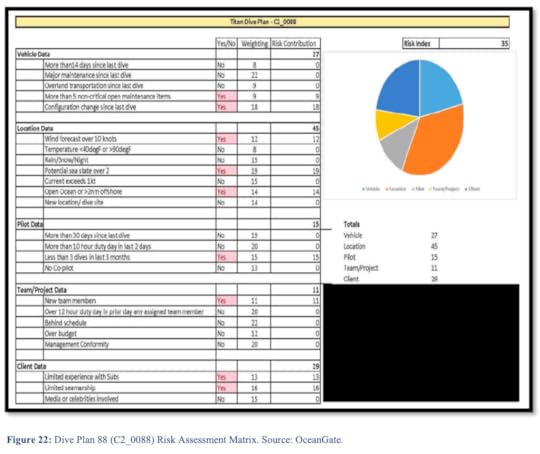

Rush assessed the risk index of the fateful dive at 35. The average risk index of previous dives was 36.

Rush assessed the risk index of the fateful dive at 35. The average risk index of previous dives was 36.Assigning accountability doesn’t help when there’s an expertise gap. Just as giving a software engineer a pager does not bestow up them the skills that they need to effectively do on-call operations work, having the CEO of OceanGate also be the pilot of the experimental vehicle did not lead to him being able to exercise better judgment about safety.

Rush’s sins weren’t merely lack of expertise, and the report goes into plenty of detail about his other management shortcomings that contributed to this incident. But, stepping back from the specifics of the OceanGate accident, there’s a greater point here that making executives accountable isn’t sufficient to avoid major incidents, if the risk models that executives use to make decisions are are out of whack with the actual risks. And by risk models here, I don’t just mean some sort of formal model like the risk assessment matrix above. Everyone carries with them an implicit risk model in their heads: this is a mental risk model.

Double bindsWhile the CEO also being a pilot sounds like it should be a good thing for safety (skin in the game!), it also creates a problem that the resilience engineering folks refer to as a double bind. Yes, Rush had strong incentives to ensure he wasn’t taking stupid risks, because otherwise he might die. But he also had strong incentives to keep the business going, and those incentives were in direct conflict with the safety incentives. But double-binds are not just an issue for CEO-pilots, because anyone in the organization will feel pressure from above to make decisions in support of the business, which may cut against safety. Accountability doesn’t solve the problem of double-binds, it exacerbates them, by putting someone on the hook for delivering.

Once again, from the resilience engineering literature, one way to deal with this problem is through cross-checks. For example, see the paper Collaborative Cross-Checking to Enhance Resilience by Patterson, Woods, Cook, and Render. Instead of depending on a single individual (accountability), you take advantage of the different perspectives of multiple people (diversity).

You also need someone who is not under a double-bind who has the authority to say “this is unsafe”. That wasn’t possible at OceanGate, where the CEO was all-powerful, and anybody who spoke up was silenced or pushed out.

On this note, I’ll leave you with a six-minute C-SPAN video clip from 2003. In this clip, the resilience engineering David Woods spoke at a U.S. Senate hearing in the wake of the Columbia accident. Here he was talking about the need for an independent safety organization at NASA as a mechanism for guarding against the risks that emerge from double binds.

(I could not get it to embed, here’s the link: https://www.c-span.org/clip/senate-committee/user-clip-david-woods-senate-hearing/4531343)

(As far as I know, the new independent safety organization that Woods proposed was not created)