Design Thinking: a Compass for Innovation in BIM and Construction

The construction industry seems to be always standing at a crossroads: since Vitruvius started idealising Greek architecture and ignored the technological advancements of his time, it’s an age-old giant, weighed down by inertia, struggling to keep pace with a world that demands flexibility, transparency, and human-centred solutions. Despite flashes of progress, too often innovation feels like window dressing: information models polished to perfection but disconnected from true collaboration, digital tools sold as salvation yet deployed as bureaucracy in disguise.

What we see is a landscape of partial transformations: buildings rise higher, but the processes behind them remain anchored in outdated hierarchies and fragmented communication. It’s a world where efficiency is measured by how well teams follow rigid plans, rather than how well they adapt, listen, and learn. And all the while, construction sites remain battlefields of delay, waste, and rework.

This is not a technological problem alone, of course. It’s a problem of mindset: of how we frame challenges, how we involve people, and how we dare to break free from the damn “this is how it’s always been done” mentality. The need for change is existential.

The dystopian landscape of construction innovation (and why we need a new map)In this environment, Design Thinking offers more than just a method: it offers a compass. Not the kind that points to a single solution or a one-size-fits-all process, but one that orients us toward what truly matters: people, purpose, and possibilities.

After all, we’re not trying to find North, are we?

After all, we’re not trying to find North, are we?A new map is needed: one that helps us navigate complexity without falling into the trap of oversimplification; one that embraces uncertainty as fuel for better outcomes rather than something to fear. The map we need does not chart a fixed route. Instead, it helps teams chart their own course, one built on empathy, experimentation, and reflection. For construction — an industry that builds the spaces where life happens — this shift is not just about improving margins or timelines, but about making the act of building itself more humane, more intelligent, and antifragile.

That being said, let’s see what Design Thinking is and, most importantly, what it’s not.

1. Design Thinking: A Tool More Than a Spell1.1. Origins: from IDEO to the motherlode of creative problem-solvingDesign Thinking as a methodological approach was forged in the gritty reality of solving complex human problems. Its modern roots trace back to the work of IDEO, a design firm that became synonymous with radical creativity applied to the everyday: how to make medical equipment safer, how to design a better shopping cart, how to humanise technology. The practice is a synthesis, a motherlode of methods drawn from engineering, architecture, anthropology, psychology, and the arts. It formalised what great designers had done instinctively for centuries: focus on people, explore ideas widely, and prototype fearlessly.

The term Design Thinking became popular as a way to bring these methods to fields beyond design, to business, education, healthcare. It’s a mindset and a toolkit meant for anyone who dares to see problems differently.

1.2. What Design Thinking is: empathy, experimentation, iteration — the tri-force of innovationAt its heart, Design Thinking is powered by three forces — not spells, not shortcuts — three enduring practices that together shape better outcomes:

Empathy: the courage to see the world through others’ eyes. In construction, this means understanding not just clients, but the end users who’ll inhabit our buildings, the workers who’ll assemble them, and the communities they’ll impact. Empathy rejects assumptions and asks: what do people truly need?Experimentation: the willingness to try, fail, and try again. Instead of endless meetings and theoretical debates, Design Thinking pushes teams to prototype, to give ideas form early and often, so flaws and opportunities surface before it’s too late.Iteration: the discipline of continuous refinement. Design Thinking doesn’t aim for perfection on the first try. It embraces cycles of testing, feedback, and improvement. This isn’t a weakness: it’s the secret to resilience in the face of complexity.These three forces form the tri-force of innovation. They won’t hand you the final answer, but they’ll equip you to build it, step by step, with your team.

1.3. What Design Thinking is not: a formula, a checklist, or a silver bullet for lazy empiresDesign Thinking’s rise in popularity has, sadly, attracted misuse. Let’s be clear about what it is not:

Not a formula. You can’t reduce Design Thinking to a flowchart or a set of sticky notes on a wall. True Design Thinking is messy, dynamic, and context-driven. It asks for judgment, not just compliance.Not a checklist. Running through “empathy interviews” or “ideation sessions” without genuine intent doesn’t make a project innovative. The value lies in how deeply teams engage with each phase, not in ticking boxes.Not a silver bullet. Design Thinking won’t fix broken organisational cultures on its own. It’s not a branding exercise for lazy empires trying to seem human-centred while clinging to outdated hierarchies. It’s not a magic word that, once uttered, transforms a rigid project into a creative marvel.To wield Design Thinking well means to respect its depth and its demands. It requires humility, curiosity, and grit, traits that no template can supply.

There’s no silver bullet for this kind of problem, sorry.2. Misconceptions and Traps

There’s no silver bullet for this kind of problem, sorry.2. Misconceptions and TrapsDesign Thinking, when wielded with integrity, can reshape how teams approach complexity. But like any powerful tool, it’s vulnerable to misuse. Here are the traps where many well-intentioned innovators — and their projects — fall.

2.1. The “template thinking” pitfallDesign Thinking invites exploration, empathy, and courage. But too often, it gets reduced to an empty ritual: sticky notes on the wall, neatly labelled stages, a well-designed slide deck that looks good in the boardroom but means nothing on the ground. This is template thinking: the illusion that creativity can be pre-packaged, applied uniformly, and produce brilliance on demand.

The danger here isn’t just wasted effort. Template thinking breeds cynicism. Teams go through the motions without questioning their assumptions or challenging the brief. They mistake activity for progress. And soon, the language of Design Thinking becomes hollow, another buzzword.

In construction, this pitfall is particularly treacherous. It’s easy to slap a “Design Thinking workshop” label onto a kickoff meeting, or to run a token brainstorming session between technical reviews. But unless the approach shapes decisions, structures dialogue, and informs real choices, it’s window dressing. The building may stand, but the opportunity to build better is lost.

2.2. The illusion of linearity: why Design Thinking is no cheat codeAnother common trap is treating Design Thinking as a straight-line process: Empathise → Define → Ideate → Prototype → Test → Success

As if following the sequence guarantees a winning solution, like entering the right combination in a game to unlock the next level.

But the real world doesn’t work this way, and Design Thinking is nonlinear by nature: teams loop back, reframe the problem, revisit insights, discard ideas, and start again.

In construction, where projects unfold across long timelines and multiple disciplines, this illusion of linearity is especially dangerous. It encourages teams to rush through the early stages — “We’ve done empathy; let’s move on!” — and lock in flawed assumptions that become costly to undo. Design Thinking’s strength lies in its flexibility, not in offering a cheat code to bypass uncertainty.

2.3. When “Design Thinking” gets hijacked by corporate overlordsPerhaps the most insidious trap is when Design Thinking is hijacked by organisations that use its language to mask business-as-usual. The terminology — empathy, co-creation, iteration — gets tacked onto projects that are, at their core, no more inclusive or innovative than before. Corporate overlords (whether in construction firms, consultancies, or client organisations) may promote Design Thinking as part of their “transformation agenda,” while simultaneously clinging to rigid hierarchies and control structures. The result? A hollow theatre of innovation. A circus in which clowns wear ties. The death of Design Thinking happens in workshops where outcomes are pre-decided, prototypes that will never see the light of day, feedback sessions where the only acceptable input is praise.

In the context of BIM and construction, this often manifests as token gestures: a design sprint that fails to inform the BIM execution plan, or a “user workshop” that’s essentially a branding exercise. The promise of Design Thinking is subverted, often not through malice but through a force far more dangerous: the fear of real change.

3. So what do we do? A motherly word of cautionThese traps aren’t inevitable. But avoiding them takes vigilance, honesty, and the willingness to ask tough questions. Are we truly listening? Are we open to rethinking? Are we using Design Thinking to serve people or to serve appearances?

3.1. The paradox of rigidity and chaos in constructionConstruction is a sector of contradictions. On paper, it is one of the most structured industries on Earth. Rigid codes, standards, contractual frameworks, and layers of approvals are designed to bring order to the colossal task of shaping the built environment. Every detail is documented, reviewed, and locked into place long before the first brick is laid or the first bolt is fastened. And yet, anyone who’s ever been on site knows the amount of chaos that lurks beneath this façade of control. Projects routinely run over budget, over schedule, and under expectation. Coordination failures, design clashes, procurement delays, and change orders are so common they’re practically baked into the process and the construction site, intended as the culmination of careful planning, often becomes a battlefield of last-minute fixes and creative firefighting.

This paradox — rigid structure breeding unpredictability — is a symptom of systems that focus on managing risk through control, rather than through adaptability and collaboration. It’s an industry trying to impose certainty where uncertainty is intrinsic.

3.2. Traditional project delivery models: the slow death of creativityMost construction projects still follow delivery models that slice the process into silos: architects design, engineers calculate, contractors build, and users — if they’re lucky — provide input after the fact. Creativity is expected only in the early design stages; after that, the mission is to stay on course, avoid disruption, and tick the boxes. But in this environment, creativity fades, suffocates. By the time a project reaches construction, opportunities for innovation — in materials, methods, sustainability, or user experience — have been sealed off by contracts, budgets, and a mindset of let’s just get it done.

BIM was supposed to change this. And to some extent, it did. But too often BIM is treated as a fancy documentation tool rather than a true enabler of collaboration and exploration. Without the mindset shift that Design Thinking offers, BIM risks becoming just another layer of bureaucracy, a digital straightjacket instead of a creative scaffold.

3.3. Why the industry craves a rebootBehind the statistics on waste, rework, and carbon emissions is a quieter truth: the people who work in construction are hungry for change. Engineers, designers, project managers, tradespeople: most know the system is broken. They see the human cost of delay, conflict, and short-sighted decisions. They feel the frustration of seeing good ideas discarded because that’s not how we do things. The industry craves a reboot, not just in technology, but in mindset. A shift from compliance to curiosity, from controlling complexity to engaging with it, from building faster to building wiser. The only ones who claim not to see how broken this industry is, are those who are profiting from these delays, conflicts, confusion and rot. And they’re those we should be bringing down with a vengeance.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the boss fight: it’s a crafting session

Unfortunately, this isn’t the boss fight: it’s a crafting sessionDesign Thinking doesn’t offer a bullet for them, as I said, but at least it offers a path forward. It’s not about discarding expertise or abandoning rigour. It’s about making space for the human factor: for empathy, dialogue, iteration, and shared ownership of the outcome. It’s about turning construction from a rigid machine into a living system that can learn, adapt, and deliver what people and the planet truly need.

The next sections will explore how we can apply Design Thinking to construction and BIM in ways that are authentic, powerful, and deeply human. Or at least they will try.

Except there is no try…4. Design Thinking Meets BIM: Forging the Digital Exosuit

Except there is no try…4. Design Thinking Meets BIM: Forging the Digital ExosuitBuilding Information Modeling is often hyped as the endgame, the set of technologies that will solve construction’s age-old woes, the One Method To Rule Them All. But let’s be honest: BIM is not the ultimate spell that, once mastered, makes all challenges vanish. Nor is it the magical artefact that guarantees victory just by owning it. Instead, BIM is a digital exosuit, a powerful augmentation of capabilities that amplifies our ability to model complexity, coordinate actors, and simulate outcomes. But it’s always the human inside the suit — the designer, the coordinator, the builder — who makes the decisions, sets the goals, and steers the mission. Without the right mindset, even the most advanced exosuit becomes a clunky liability rather than a tool for good. Design Thinking is one of the things that might breathe life into BIM. It helps teams use the technology not just to document what is, but to imagine what could be and to bring that vision to life collaboratively.

Design Thinking might to BIM:

empathy for users, builders, and maintainers, ensuring the model serves real needs, not just contract requirements;rapid, low-risk prototyping, using models as conversation starters rather than final products;feedback loops and iteration, keeping the model alive and evolving as understanding deepens;cross-disciplinary dialogue, where models become common ground for architects, engineers, contractors, and clients.5 practical examples of Design Thinking + BIM workshopsHere are five workshop formats where Design Thinking and BIM join forces at key stages of the construction process, divided into stages, for your consideration and use.

5.1. Early design: user empathy + conceptual modelling workshopGoal: align the conceptual BIM model with actual user needs and site context

Stakeholder mapping and empathy interviews with future users, operators, and neighbours;Synthesis of needs into personas and journey maps;Quick massing studies and spatial scenarios created directly in BIM (or exported from sketching tools into BIM)Feedback session using VR or walkthroughs of the conceptual modelOutcome: a model that starts with people, not geometry, and captures experiential priorities from day one.

Phase 1 — Stakeholder Mapping & Empathy InterviewsThis phase aims at identifying who truly matters beyond the client’s organisational chart. To map primary users, maintenance teams, visitors, and overlooked voices (e.g. cleaning staff, delivery drivers), we conduct short empathy interviews to capture their pains, joys, and daily realities.

Tools:

Whiteboard / Miro / MURAL for stakeholder mapping;Empathy map templates (digital or paper);Audio recorder or notes app (for interview insights).Facilitator Tips:

Push beyond “official” stakeholders. Ask: who uses this space at 6 AM? Who’s here at midnight?Be human. Leave technical jargon at the door during interviews: this is about stories, not specs.Keep interviews short (10–15 mins) but focused. What frustrates you? What delights you?Phase 2 — Persona & Journey SynthesisInterview findings can be distilled and condensed into vivid personas (fictional but evidence-based) and their journeys mapped through the future space: arrival, movement, use, and departure.

Tools:

Persona templates;Journey mapping boards (digital or paper);Large-scale printout of site plan / context;Facilitator Tips:

As usual, give each persona a name and sketch: people connect better with “Gigi the Night Guard” than “Security Staff.”Be ruthless in eliminating assumptions. Anchor every persona trait and journey point in a real insight.Use colours or symbols to mark pain points vs. positive experiences on the map.Phase 3 — Conceptual Massing in BIMTranslate user needs into basic spatial forms, explore scenarios through massing models that prioritise flows, adjacencies, and feel over detail.

Tools:

BIM authoring tools with a massing capability;Rapid modelling extensions (Dynamo scripts, Grasshopper for Rhino inside Revit);Large display / VR headset for walk-throughs.Facilitator Tips:

Resist the urge to perfect geometry. The goal is to test ideas, not create deliverables.Let users (or their advocates) react live to the massing: does this make your day easier or harder?Keep models modular and editable: this is a sandbox, not a blueprint.Phase 4 — Feedback & ReflectionPresent conceptual models to the group, gather reactions, and document insights to refine or rethink forms. Encourage reflection on how well the massing supports journeys mapped earlier.

Tools:

Commenting directly in a viewer (e.g. BIM 360, Navisworks, Solibri);Physical printouts or pin-ups for markups;Sticky notes or digital comment tools.Facilitator Tips:

Make space for quiet reflection as well as open discussion. Not everyone speaks up in big groups.Ask: what surprises you? What worries you? Don’t settle for polite nods.Capture all feedback, even the “off-topic” bits. Sometimes gold hides in unexpected comments.Notes to the FacilitatorStay humble: this is not your model, it’s the users’. You’re the guide, not the hero of this story.Expect mess: insights will conflict, needs will clash. That’s not failure but fuel for design.Keep it moving: don’t let the group get stuck perfecting diagrams or models at this stage. The goal is understanding, not precision. 5.2. Schematic design: Clash of needs, not just clash detection

5.2. Schematic design: Clash of needs, not just clash detectionGoal: resolve conflicting functional requirements before they harden into costly design decisions

Cross-disciplinary Design Thinking workshop (architects, MEP engineers, structural, contractor);Visualise conflicting priorities in the BIM environment (e.g., spatial vs. mechanical needs);Ideation session for “both-and” solutions, not just trade-offs;Rapid modelling of mock-ups to test ideas.Outcome: reduced late-stage conflicts, with BIM supporting negotiation rather than just reporting clashes.

Phase 1 — Cross-Disciplinary Need MappingBring together architects, engineers (MEP, structural), contractors, and other key players. Each discipline maps their functional, spatial, and technical priorities without jumping to solutions.

Tools:

Large shared plan views in BIM viewer or as printouts;Colour-coded stickers or digital tags for each discipline;Templates for “need statements” (e.g. We need [X] here so that [Y])Facilitator Tips:

Insist that each need be framed in human or project value terms (so that…), not just technical specs;Watch for territorial behaviour. Gently remind the group that we’re solving a puzzle, not staking claims.Encourage clarity: no vague needs like flexible space without explaining flexible for what.Phase 2 — Visualising Conflicts in BIMOverlay needs in the modelling environment, making competing requirements visible: not just pipe vs. beam, but circulation vs. services, light vs. structure, etc.

Tools:

BIM coordination tools (Navisworks, Solibri, etc.)Clash detection, but configured to highlight functional clashes (e.g. clearance zones, daylight paths);Layered views to isolate different systems.Facilitator Tips:

Avoid turning this into a pure geometry exercise. The key is to show where intended uses conflict, not just objects.Use overlays to tell stories: This duct path takes away headroom from the main entrance. Make impacts tangible.Stay neutral. Your role is to reveal tension points, not to solve them (yet).Phase 3 — Ideation for “Both-And” SolutionsRun rapid idea generation to find solutions that meet multiple needs simultaneously. Focus on both-and, not either-or.

Tools:

Sketch overlays (digital or tracing paper on printouts);Collaborative markup tools in the viewer;Quick digital massing adjustments.Facilitator Tips:

Frame challenges as opportunities for creativity, not problems to be grudgingly solved;Timebox ideation rounds to prevent analysis paralysis;Celebrate wild ideas before filtering: sometimes, the outlandish solution sparks the best compromise.Phase 4 — Rapid Mock-Ups & Feasibility Tests in BIMPrototype top ideas directly in BIM (or parametric tools linked to BIM). Run quick feasibility tests: space, cost, constructability.

Tools:

BIM authoring tools in massing / early systems mode;Dynamo / Grasshopper for quick parametric alternatives;Quantity takeoff tools for basic cost/volume checks.Facilitator Tips:

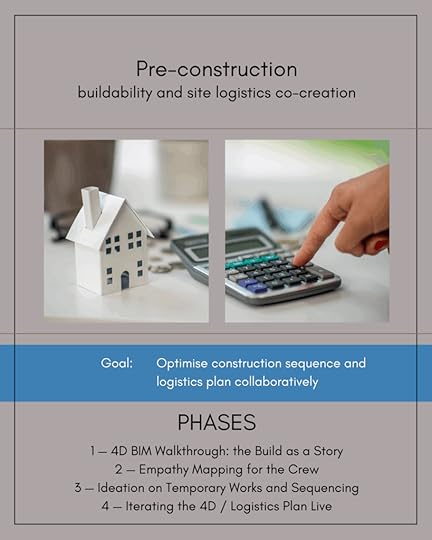

Keep models rough. The goal is to test ideas, not create detailed designs.Invite commentary from those who’ll build or install: does this work on-site?Document what was tried and why solutions were accepted or set aside.Notes to the FacilitatorMind the balance: let every discipline speak, but watch the clock. Protect space for solutions, not just descriptions of the problem.Defuse tension: when clashes feel personal, remind the group: The building needs all of us. There are no villains here.Anchor in purpose: when choices get tough, come back to the end users and project goals — that’s your North Star. 5.3. Pre-construction: Buildability and site logistics co-creation

5.3. Pre-construction: Buildability and site logistics co-creationGoal: optimise construction sequence and logistics plan collaboratively

Field team, planners, and designers gather around a 4D BIM simulation;Empathy mapping of site crew needs (access, safety, material flow);Ideation on temporary works, sequencing, and staging;Iterate the 4D model live during the workshop.Outcome: a logistics plan that respects on-site realities, co-owned by the people who’ll execute it.

Phase 1 — 4D BIM Walkthrough: the Build as a StoryUse 4D BIM (or a simplified sequence visualisation) to “tell the story” of the build. Let all participants — designers, planners, contractors, trades — walk through the planned sequence, observing site flows, pinch points, and blind spots.

Tools:

4D BIM viewer (Synchro, Navisworks Timeliner, ACC build with scheduling plug-in);Large screen or immersive VR headset for small groups;Timeline overlays on site plans.Facilitator Tips:

Frame this as storytelling, not checking compliance: what’s it like to build this?Slow down at key stages: site setup, major transitions, critical lifts.Watch for moments of confusion or concern and call them out with care.Phase 2 — Empathy Mapping for the CrewMap what the site crews will need at different stages: safe access, clear material flows, storage, clean work areas, shelter, utilities. Highlight where the current plan helps or hinders them.

Tools:

Empathy map templates focused on construction crew needs;Site plan printouts or digital overlays;Colour-coded markers for needs (access, storage, safety, welfare)Facilitator Tips:

Focus on real people: not “the contractor,” but the scaffolders, the concrete team, the fit-out crew;Ask field participants to describe their experience in similar projects: where did things fall apart?Capture small details: where will people eat lunch? Where do deliveries queue? These matter.Phase 3 — Ideation on Temporary Works, Sequencing, StagingGenerate ideas for improving buildability: better sequencing, smarter staging, temporary works that enhance safety and flow.

Tools:

Sketch overlays on site logistics plans;Information model massing adjustments (temporary structures, crane zones, laydown areas);Physical props: blocks or cardboard for quick spatial mock-ups.Facilitator Tips:

Grant permission to challenge assumptions: what if we flipped the sequence? What if we staged this differently?Ensure site operatives have an equal voice: their ideas are often the most practical.Document the logic behind each idea: not just what, but why.Phase 4 — Iterating the 4D / Logistics Plan LiveAdjust the 4D model or logistics drawings in real time to test the most promising ideas. Run quick simulations of impacts: time, space, safety.

Tools:

4D tools (same as Phase 1) with editable timeline;Live editing in logistics CAD/BIM layers;Quick cost or risk assessment tools (even simple spreadsheets)Facilitator Tips:

Focus on big wins: don’t get bogged down perfecting every detail.Highlight how changes improve worker experience as well as program outcomes.Capture decisions clearly, and flag what needs deeper follow-up offline.Notes to the FacilitatorHold space for reality: what looks clean in a model may be messy on-site. Trust — and ask for — the wisdom of those who’ve built before.Champion respect: this is where design and construction cultures can clash. Be the voice that says: we’re all builders here.Keep sight of purpose: a logistics plan isn’t just about efficiency, it’s about building safely, humanely, and with pride. 5.4. Construction stage: problem-solving sprints

5.4. Construction stage: problem-solving sprintsGoal: rapidly address unforeseen site issues with creative, practical solutions

Small, focused Design Thinking sprint with field staff, designers, and BIM team;Frame the problem clearly using data from BIM and site observations;Sketch and model alternative solutions in BIM on the fly;Evaluate trade-offs with input from all disciplines.Outcome: agile, well-informed decisions that keep the project moving without compromising quality.

Phase 1 — Frame the Problem ClearlyBring together the smallest possible team of relevant players (field staff, designers, BIM team, planner). Clarify what the issue is, who it impacts, where it sits in the sequence, and why it matters.

Tools:

BIM viewer focused on the affected area;Photographs, drone footage, or 360 site captures;Simple problem framing template (e.g. We see [issue] at [location] which affects [process] because [reason])Facilitator Tips:

Don’t let people jump to solutions too soon. Make sure the problem is understood by all.Ask: what do we know? What don’t we know?Be inclusive: sometimes the most valuable insights come from quieter voices (e.g. a site supervisor or trade lead).Phase 2 — Ideate Alternatives FastRun a time-boxed burst of idea generation (think: 30 minutes max). Focus on generating multiple approaches, no matter how unorthodox.

Tools:

Quick hand sketches on paper or tablet;Mark-up directly in model viewer (e.g. redlines, annotations)Preloaded standard detail libraries for rapid referencingFacilitator Tips:

Enforce “no bad ideas” in this phase: even half-formed thoughts can trigger breakthroughs.Use a round-robin format to ensure everyone contributes.If tension rises, remind the team: We’re here to solve, not to blame.Phase 3 — Prototype Solutions in BIM + Reality CheckMock up top ideas directly in the BIM model (at massing/detail level as appropriate). Quickly test for impacts on adjacent systems, schedule, and cost.

Tools:

BIM authoring tool or viewer with markup / edit functions;Clash detection or coordination module;Quantity takeoff or cost estimator (even simple volume-based checks)Facilitator Tips:

Keep prototypes rough and flexible: this is for testing, not for issuing.Run basic checks live: does this clash? Can this be built?Involve the planner early: sequence impacts can kill good ideas if not addressed.Phase 4 — Decide + Document the WhySelect a path forward, document the rationale, and flag what needs formal approval. Focus on alignment: Why this solution? How will we implement? Who needs to know?

Tools:

Shared action log (e.g. in ACC or Trello);Annotated model snapshot or marked-up drawings;Decision record template (issue, options considered, choice, reasoning)Facilitator Tips:

Be decisive: the team needs clarity to act.Make sure everyone knows their next step.Document why a solution was chosen: future you will thank you when questions arise.Notes to the Facilitator

Keep it focused: site problem-solving sprints aren’t about exploring the galaxy. They’re about fixing the ship so it can sail on.Stay kind: stress levels can be high. Your calm, inclusive tone will help the team think clearly.Leave a trail: good decisions made fast can still stand up later if you leave a clear record of how you got there. 5.5. Handover and operation: Post-occupancy insight and BIM model refinement

5.5. Handover and operation: Post-occupancy insight and BIM model refinementGoal: capture operational feedback to improve the as-built BIM and inform future projects

Interviews and observation of users in the finished space;Map pain points and delight points in the building experience;Workshop to translate insights into model adjustments (e.g., tagging changes, data enrichments);Identify patterns to guide future designsOutcome: a smarter asset information model that reflects the building as it’s truly used, closing the loop between design intent and lived reality.

Phase 1 — Capture Lived ExperienceEngage with occupants, operators, and facilities teams to understand how the building supports (or frustrates) daily life. Focus on mapping real behaviours and needs, not just collecting complaints.

Tools:

Structured interviews and informal chats (recorded or noted);Observation checklists (e.g. entry flows, use of shared spaces, maintenance access);Photo/video diaries from users (if feasible).Facilitator Tips:

Go beyond managers. Talk to those who interact with the space daily: cleaners, security, reception, technical maintenance.Be present on-site: observe quietly, without interrupting. The details people don’t mention are often the most telling.Focus on both delights and pain points: you need a balanced picture.Phase 2 — Map Insights VisuallyTranslate feedback into annotated floor plans, journey maps, or BIM overlays. Make invisible patterns visible: where discomfort, inefficiency, or unexpected behaviors occur.

Tools:

Annotated PDFs of plans or sections;Digital markups in BIM viewer;Journey mapping templates for key personas.Facilitator Tips:

Visuals are key: most people engage far better with marked-up plans than long lists of comments;Use colour codes for delight, neutral, pain points, and for operational vs. user experience issues;Involve FM teams early: they’ll help validate patterns and flag what’s feasible to adjust.Phase 3 — Translate into BIM RefinementsUpdate the BIM model to reflect reality: tag changes, enrich data, and document operational insights. Where possible, embed feedback for future reference (e.g. comments linked to elements).

Tools:

BIM authoring tool with tagging / property editing;CDE or FM platform linked to the as-is information model (e.g. COBie data updates);Issue tracking or feedback log toolsFacilitator Tips:

Prioritise updates that add long-term value: asset tags, access info, key maintenance data;Don’t try to fix everything at once. Focus on what helps the building work better or informs future designs.Flag gaps in the model that made post-occupancy feedback hard to capture — that’s gold for the next project.Phase 4 — Identify Patterns for Future DesignsSynthesize insights into design principles, guidelines, or “lessons learned” that can inform future BIM models, standards, and strategies.

Tools:

Summary report templates;Visual dashboards (e.g. Power BI linked to data);Team debrief session (in-person or virtual)Facilitator Tips:

Frame this as positive learning: no finger-pointing, just collective wisdom.Keep it short and focused: one page of key patterns beats a 50-page report no one reads.Share findings beyond the project team. The next design will thank you.Notes to the FacilitatorChampion the users: they lived in the space before we did. Their voices matter most now.Fight the “it’s done” mindset: a building isn’t finished at handover. Help the team see this as the next chapter, not an afterthought.Protect the data: this is precious knowledge. Make sure it’s stored where it will be seen and used, not lost in forgotten folders. 6. Applications Beyond the Blueprint

6. Applications Beyond the BlueprintDesign Thinking’s value in construction doesn’t stop at creating better designs or refining information models. Its principles — empathy, iteration, co-creation — can drive positive change across the full construction ecosystem, wherever humans, tools, and environments intersect.

6.1. Design Thinking for Safety, Sustainability, and Site LogisticsSafety plans, sustainability strategies, and site logistics are too often treated as add-ons, documents to comply with, not living systems to co-create. Design Thinking invites teams to approach these areas differently:

For safety: instead of top-down rules, involve workers in mapping risk from their perspective. Prototype safer workflows, test new signage or procedures collaboratively, and iterate based on real feedback.For sustainability: use empathy tools to connect design choices to community and environmental impact. Engage stakeholders in exploring how materials, energy systems, and construction methods affect their world, and prototype lower-impact alternatives early.For site logistics: map site flows as human journeys, not just truck paths. Co-design layouts that respect workers’ experience, from arrival to departure, and test them in real time through rapid simulations or mock-ups.In each case, Design Thinking shifts the focus from compliance to ownership, turning these plans into tools teams believe in.

6.2. How Gamification and User-Centric Design Reshape Construction SitesConstruction sites are complex, high-pressure environments, and often designed around the work rather than the people doing it. Design Thinking, fused with principles of gamification, can transform that dynamic. Gamification brings feedback, motivation, and clarity. Imagine safety systems that reward proactive hazard reporting, or logistics apps that turn clean, efficient work zones into a shared team goal. User-centric site design recognises workers as users of space. This means considering their comfort, cognitive load, and daily rituals. Wayfinding that reduces stress, break areas that restore energy, and workflows that support focus, all things essential to building better.

These applications go beyond models and drawings. They ask the industry to see the site — and the people within it — as worthy of design attention in their own right.

Epilogue: the Endless Frontier of Human-Centred Construction TechnologyWe often talk about technology in construction as if it’s the end of the story, as if once we master BIM, automation, AI, or digital twins, of whatever the fuck there’s to master this time, the mission is complete. But in truth, it’s what we choose to do with them that defines our impact.

Design Thinking reminds us that technology is not an answer in itself. It’s a means to ask better questions, a way to build not only structures but systems that learn, adapt, and care for the people they serve. In this sense, the frontier is endless because people’s needs, dreams, and contexts will keep evolving, and so must we.

The real challenge is having the courage to stay human-centred as the landscape shifts. To keep asking: who are we building for? What do they need? How can we work together to deliver it, wisely and well? This is the frontier that matters. And it’s wide open for those ready to explore it with integrity, imagination, and the strength to resist the easy path of business-as-usual.

Welcome to Westworld

Welcome to Westworld