AI From 1986, Reading Minds...Badly

The first time I wrote the words “artificial intelligence” in a published article was, apparently, in 1986.

Here’s what was exciting (then!) about that 1986 AI: It was the kind of autocomplete function that we all experience today when we try to text “mortadella” and it gets changed to “mortgage.”

You know, then the text goes out as: “Hey, you good with a mortgage sandwich for lunch?”

I often use Newspapers.com to find old articles. It’s a searchable archive of more than 29,000 newspapers, some going back to the 1800s. Included are every newspaper I’ve ever written for. (I haven’t been writing since the 1800s, though sometimes it feels that way.) These days, like just about everyone else, I’m writing, thinking, and talking about AI a whole lot. So I wondered when I first encountered it as a journalist covering technology.

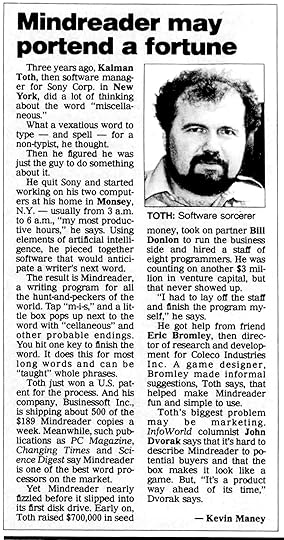

Turns out it was 1986, and once I saw the story, I realized it was thanks to a burly bear of a guy named Kalman Toth and his software product called Mindreader.

I vaguely remember Toth. I do remember Mindreader because he let me test it out. The software was the right idea too early. That it worked at all was miraculous. But it didn’t work well. I’m pretty sure I turned it off before long.

The Mindreader back story: Toth worked on software for Sony in its New York offices. For Lord knows what reason, he got thinking about the word “miscellaneous” and how hard it can be to spell and to type that word out. He quit Sony and started writing code to solve the miscellaneous problem.

The sentence I wrote when I first typed the words “artificial intelligence” was this: “Using elements of artificial intelligence, he pieced together software that would anticipate a writer’s next word.”

Yeah, so when you’d type “mis” it would automatically add “cellaneous.” Mind blown!

Toth started a company, Businessoft, to sell Mindreader at $189 a pop. He landed a seed investment of $700,000, but failed to get any more funding.

I don’t know much about what happened to Toth or Businessoft after I wrote about him. In 1988, another company, Brown Bag Software, released Mindreader 2.0. A site called WinWorld acknowledged that Mindreader was “originally written by Kalman Toth of BusinesSoft (sic).” You can go to that page to see what Mindreader looked like. Whoever wrote about it also concluded that the software wasn’t that useful: “The majority of its suggestions seemed irrelevant, and the auto complete does not really act as a spell checker.”

Otherwise, though, I searched all over the internet. Toth, his company and his pioneering AI seem to have vanished in the 1980s. Another software company called BusinesSoft was founded in Bulgaria in the 1990s – and still exists. It doesn’t do anything like Mindreader.

Toth is one of those too-early innovators lost to history. What he started with Mindreader has become part of our everyday lives. As I’m typing this in a Google Doc, it’s offering to complete words and sentences.

What I know now that I didn’t in 1986 is that Mindreader was a casualty of running afoul of the adjacent possible.

When my firm works with leadership teams on creating new market categories, it always involves a conversation about the adjacent possible. If you consider that there is a “possible” (all the technology that we already use) and the “not-yet-possible” (technology not yet invented or not yet very workable), then there is a border between them called the adjacent possible.

When a new technology lands in the adjacent possible, it’s new enough to be cool and amazing but mature enough to actually work well. Which is when a new technology catches on.

Mindreader was too far into the not-yet-possible. By the time more advanced versions of autocomplete entered the adjacent possible, Toth’s company had long run out of money and faded away.

(One related point: If a company is building a product that lands squarely in the possible, it’s entering an existing market and trying to scrape out a few points of market share. Those companies aren’t creating new market categories.)

Anyway, back to Mindreader. Today’s generative AI is sometimes described as superpowered autocomplete, kind of a great-great-great-grandchild of Mindreader’s technology. In fact, when I asked Anthropic’s Claude to describe how its technology works, it responded:

Think of a large language model like an incredibly sophisticated autocomplete system that has read virtually everything ever written on the internet. When you type a message, it doesn't actually “understand” what you're saying in the way humans do – instead, it's making incredibly nuanced predictions about what word should come next based on the patterns it learned from analyzing billions of text examples.

Claude went on:

It's like having a friend who has memorized every conversation, book, and article ever written, and when you start a sentence, they can finish it by drawing on all those patterns – except this friend processes all that information simultaneously and can predict not just the next word, but entire coherent responses.

In other words, it’s a lot like a mindreader.

—

This is the article as it appeared in USA Today on February 13, 1986, as accessed on Newspapers.com: