Poetry Reading List for Architects

Architecture, as a discipline, has long claimed dominion over the notion of space. From Vitruvius’ triad of firmitas, utilitas, venustas to Le Corbusier’s declaration of the house as “a machine for living in”, architects have positioned themselves as the stewards of spatial order. Yet, for all the technical precision and aesthetic theory, architectural discourse often reduces space to geometry, structure, and function, what the eye can measure and the hand can build.

Le Corbusier once wrote, “Architecture is the learned game, correct and magnificent, of forms assembled in light.” But in this emphasis on light, form, and assembly, something slips through the cracks: the lived, felt, and imagined qualities of space. Juhani Pallasmaa, in The Eyes of the Skin, laments this very reductionism, arguing that modern architecture has become a “retinal art”, too focused on vision at the expense of the full sensory and emotional experience of space. As you know, I’ve never been a fan of the crow.

Space in architectural discourse can become rigid, formalised, a domain of grids, plans, and sections. But human experience of space is messier, more fluid, and harder to pin down. And this is where poetry begins to offer its lessons.

Poetry, unlike architecture, is unburdened by gravity, budget, or building code. It can conjure vast cathedrals in a single line or collapse entire worlds into the tight confines of a haiku. Where architects draw elevations and axonometrics, poets map the inner landscapes of memory, sensation, and longing.

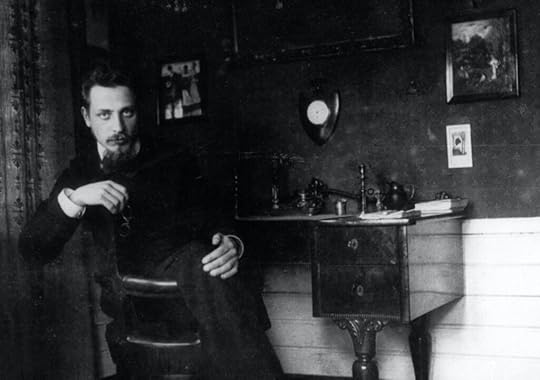

Consider Rainer Maria Rilke’s evocation of space in Duino Elegies:

“Ah, but what can we take along

into that other realm? Not the art of looking,

which is learned so slowly, and nothing that happened here.

Nothing. The sufferings, then. And, above all, the heavy,

the ponderous weight of space…”

Here, space is not an external void to be measured but a burden we carry within us. The poet reminds us that space is as much an emotional and existential construct as it is a physical one.

Similarly, Emily Dickinson’s “I dwell in Possibility / A fairer House than Prose” reimagines the very boundaries of habitation. Her “house” is a metaphor for the infinite potential of the imagination, a space that expands precisely because it is unbuilt.

The Value of Cross-Disciplinary InsightsWhy, then, should architects — those who give material form to our shared environments — pay heed to poets? Because poets help us remember what architecture sometimes forgets: that space is not just seen, but felt; not just planned, but lived. The poet teaches us to be attuned to atmospheres, thresholds, silences, and the invisible contours of experience.

As architect Peter Zumthor reflects, “Architecture is not about form, it is about many other things. The light and the air. The smell and the sound. The way things feel. The memory of a space.” These are precisely the elements that poetry has always known how to capture. When architects borrow the poet’s sensitivity, they can aspire to create spaces that resonate not just in the mind’s eye but in the body’s memory.

This post proposes that five poets — each with a distinct way of understanding and shaping space through words — can help architects (and all of us) see space anew. They remind us that space is not simply a void between walls, but a condition shaped by perception, history, and desire.

Possibly my favourite project by Peter Zumthor.Poet #1: Emily Dickinson and the Architecture of Interior SpaceMicrocosms of a Room and the Mind

Possibly my favourite project by Peter Zumthor.Poet #1: Emily Dickinson and the Architecture of Interior SpaceMicrocosms of a Room and the MindEmily Dickinson, the reclusive poet of Amherst, lived much of her life within the bounds of a single house and, more precisely, within the confines of her small upstairs room. Yet in her poetry, this narrow space becomes a boundless universe, a microcosm where the architecture of the mind unfolds in endless variation.

In one of her most famous lines, Dickinson declares:

“The Brain – is wider than the Sky –”

“For – put them side by side –”

“The one the other will contain”

“With ease – and You – beside –”

Here, spatial scale collapses: the brain, enclosed within the skull, out-expands the sky itself. Dickinson’s room, like her brain, becomes a site where immensity is not measured by external dimensions, but by the reach of thought and imagination.

This stands in stark contrast to the modernist architect’s fascination with open plans and expansive vistas. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously championed “less is more”, but his minimalism aimed at clarity and openness. Dickinson’s minimalism, on the other hand, finds vastness in enclosure, a reminder that scale is a matter of perception as much as proportion.

Emily in a family portrait (she’s the one on the left)How Minimalism and Enclosure Create Infinite Worlds

Emily in a family portrait (she’s the one on the left)How Minimalism and Enclosure Create Infinite WorldsDickinson’s physical world was one of walls, windows, and limited horizons. Yet this very constraint fostered a deeper engagement with the textures of inner space. The smallness of her environment was not a prison but a portal:

“A Prison gets to be a friend –”

“Between its Ponderous face”

“And Ours – a Kinsmanship express –”

Here, enclosure generates intimacy, familiarity, and even affection. Dickinson teaches us that the bounded space can nurture an expansive interiority, much as a cloister or a cell might provide the contemplative with room for spiritual wandering.

Peter Zumthor echoes this sensibility when he writes in Atmospheres:

“I try to create buildings that are loved. Loved by the people who live in them, who work in them, who encounter them. This is only possible if architecture has something of the quality of silence about it.”

Dickinson’s space is precisely that: silent, intimate, inwardly resonant. Where architects sometimes seek to dissolve boundaries in the name of transparency or flow, Dickinson’s poetry reminds us of the value of shelter, of places where the self can retreat, reflect, and expand inwardly.

Managing to be intimate in a vast space, and silent in a public venue, is possibly one of Zumthor’s highest achievements in his Thermæ of Vals.Lessons for Architects on Introspection and Scale

Managing to be intimate in a vast space, and silent in a public venue, is possibly one of Zumthor’s highest achievements in his Thermæ of Vals.Lessons for Architects on Introspection and ScaleWhat can architects learn from Emily Dickinson? First, that scale is not an absolute. A small room can contain infinite possibilities if it engages the imagination and the senses.

Second, that introspection requires spaces that allow for withdrawal as much as for interaction. The rush toward openness in contemporary design risks neglecting the human need for pause, solitude, and inwardness. See any open space for reference. As Frank Lloyd Wright observed: “space is the breath of art.” But Wright’s breath often took the form of grand, sweeping volumes. Dickinson reminds us that sometimes, breath is drawn deepest in the quiet stillness of a small, enclosed space.

Architects might consider, then, how to design not only for movement and spectacle, but for stillness and thought. In Dickinson’s minimal, bounded spaces, we find a model for architecture that honours the private vastness of the mind, a space where, as she wrote, “possibility is a fairer House than Prose.”

Poet #2: Rainer Maria Rilke and the Poetics of ThresholdsSpaces of Transition and Liminality

Poet #2: Rainer Maria Rilke and the Poetics of ThresholdsSpaces of Transition and LiminalityRainer Maria Rilke’s work brims with a profound sensitivity to spaces that lie between: between inside and outside, life and death, the visible and the invisible. His poetry is attuned to thresholds, those in-between zones where identity dissolves and transforms. As he writes in the Duino Elegies:

“For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror,

which we are still just able to endure,

and we are so awed because it serenely disdains

to annihilate us.”

Here, beauty itself is liminal: poised at the edge of terror, existing in a space of ambiguity. Rilke’s spatial imagination is one of doors left ajar, windows opening onto darkness, stairways that vanish into silence. His houses, cities, and rooms are not static enclosures but vessels of becoming, passage, and transformation.

This echoes the architectural reflections of Juhani Pallasmaa, who writes: “the door handle is the handshake of the building.” Pallasmaa, like Rilke, focuses on the moment of crossing, the tactile encounter at the threshold that defines our relationship with space. Rilke teaches architects to cherish these transitional moments not as mere connectors between “real” spaces, but as spaces of their own, charged with meaning.

The modular building is possibly one of Juhani Pallasmaa’s most enchanting projects.The Duino Elegies and the Metaphorical House

The modular building is possibly one of Juhani Pallasmaa’s most enchanting projects.The Duino Elegies and the Metaphorical HouseIn the Duino Elegies, Rilke invokes the metaphor of a house not as an object of shelter, but as an existential condition. The house is where the human spirit negotiates its place between the earthly and the eternal. In the First Elegy, he speaks of “the open house of the earth”, a place where angels, humans, and animals intermingle in uneasy proximity. His imagery suggests that our dwellings are never truly ours: they are shared with ghosts, memories, and the forces of nature. The house becomes a threshold in itself, a site of dialogue between permanence and flux. As he writes: “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the angels’ hierarchies?” The house, in Rilke’s hands, is less a fortress than a question—a permeable structure open to the winds of the unseen.

This resonates with the ethos of architects like Peter Zumthor and Álvaro Siza, who design not with the arrogance of control but with humility toward place. Zumthor notes:

“I have often thought that my buildings try to be a vessel for the human soul rather than monuments to the architect’s ego.”

Rilke’s poetic houses, likewise, are vessels for the soul’s uncertainties.

One of Alvaro Siza’s monuments to his poetic approach is the Tea House in Porto.What Architects can learn about Ambiguity and Becoming

One of Alvaro Siza’s monuments to his poetic approach is the Tea House in Porto.What Architects can learn about Ambiguity and BecomingRilke’s gift to architecture lies in his reverence for ambiguity: the refusal to define, the embrace of what is in process. In a world where architectural practice often privileges clarity, function, and resolution, Rilke asks us to consider the virtues of the unresolved, the liminal, the space of becoming.

Thresholds, in Rilke’s poetics, are not obstacles to cross but experiences to inhabit. They invite us to dwell in uncertainty, to attune ourselves to the subtleties of change. As Louis Kahn famously said: “A room is not a room without natural light.” But Rilke might counter that a room is not a room without shadow, without mystery, without the sense of what lies beyond.

For architects, Rilke’s work suggests designing spaces that honour these moments: foyers that slow our passage, staircases that invite pause, windows that frame the ungraspable. To design with Rilke’s sensitivity is to create buildings that do not merely shelter bodies but accompany souls in their ceaseless transition.

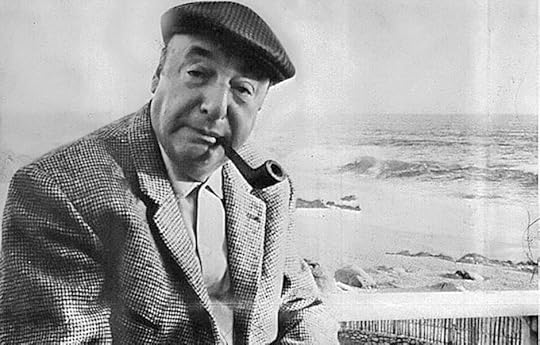

Poet #3: Pablo Neruda – The Tactile and the ElementalOdes to Everyday Objects and Spaces

Poet #3: Pablo Neruda – The Tactile and the ElementalOdes to Everyday Objects and SpacesPablo Neruda’s Odas elementales are celebrations of the ordinary. In these poems, he sings the praises of spoons, onions, chairs, socks, and the most unremarkable of rooms. Far from trivial, these odes elevate the material world to the realm of the sacred. Neruda writes:

“I love things with a fervour

that I can’t explain:

the metal compass and the carpenter’s plane,

the carpenter’s saw,

the smell of wood,

and the smell that unfolds

from the firewood.”

Here, the poet’s gaze lingers not on monumental spaces or heroic structures, but on the humblest artefacts that shape daily life. Neruda understands that space is not made grand by scale, but by its relationship to the objects and gestures that inhabit it.

This attention to the everyday echoes the wisdom of architects like Peter Zumthor, who writes: “Materials have the capacity to awaken the emotions in us. A certain material, or the sound of it, or the way light falls on it, can transport us to another place in our memory.” Neruda’s odes remind us that architecture begins not with abstractions, but with the intimate dialogue between hand, tool, and matter.

Architecture as Intimacy with MaterialityNeruda’s poetry invites architects to rediscover materiality not as a means to an end, but as an end in itself. His words caress surfaces, textures, smells. He praises the density of wood, the weight of stone, the grain of bread. For Neruda, to know the world is to touch it, to breathe it in, to taste its presence.

His Ode to the Table exalts this sensorial bond:

“The world is a table… engulfed in honey and smoke smothered by apples and blood. The table is already set, and we know the truth as soon as we are called…”

In the same way, architecture that is truly human must honour the table, the threshold, the window sill, the small-scale elements that root us in place. This perspective counters the tendency in contemporary design toward sleekness and dematerialisation, where glass facades and synthetic skins often mask the tactile reality of structure. Neruda’s elemental poetics call to mind the ethos of Alvar Aalto, who observed: “Form must have a content, and that content must be linked with nature and the human soul.” Neruda’s harmonies of wood, stone, bread, and cloth challenge architects to rediscover the sensual unity of material and life.

Designing with the Senses, not Just the EyeModern architecture, with its privileging of vision, has too often neglected the full range of human sensation. Neruda’s poetry compels us to design for touch, smell, taste, and sound, to create spaces that embrace the body, not just impress the eye. His Ode to the Onion reminds us that even a simple aroma can evoke entire worlds: “You make us cry without hurting us.”

In the same spirit, Juhani Pallasmaa, in The Eyes of the Skin, urges architects to reject ocularcentrism and engage all the senses: “Every touching experience in architecture is multi-sensory; qualities of matter, space, and scale are measured equally by the eye, ear, nose, skin, tongue, skeleton, and muscle.”

Neruda, through his poetry, teaches architects to approach space as an orchestra of sensations where the roughness of a wall, the creak of a stair, or the coolness of a stone floor become as vital as the play of light or the sweep of form. Designing with Neruda’s spirit means shaping spaces where materiality is not hidden, but celebrated; where the sensual encounter with the world is at the heart of the architectural experience.

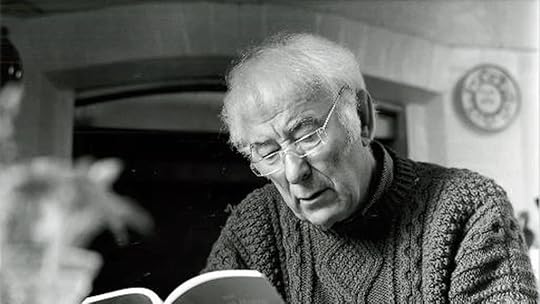

Pablo NerudaPoet #4: Seamus Heaney, excavating Memory in the LandscapeThe Layered Spatiality of History and Soil

Pablo NerudaPoet #4: Seamus Heaney, excavating Memory in the LandscapeThe Layered Spatiality of History and SoilSeamus Heaney’s poetry draws deeply from the soil, not just as physical matter, but as a medium of history, memory, and identity. His verses are filled with bogs, fields, and furrows, where each layer of earth conceals the traces of those who have gone before. In Digging, Heaney writes:

“Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.”

The poet’s act of writing mirrors the act of excavation. Both the farmer’s spade and the archaeologist’s trowel unearth hidden narratives, buried truths, and forgotten lives. In Heaney’s hands, the landscape is no blank canvas: it is a stratified archive, rich with stories waiting to be revealed.

Architects, too, work upon the land, but too often they erase rather than reveal its histories in the name of progress or supposed poetics. Heaney’s sensitivity to the earth challenges designers to see the site as a text to be read, not a page to be cleared. His bog poems, in particular, invite us to contemplate land as both witness and participant in human drama, a place where time is inscribed in layers of peat and mud.

Space as Palimpsest: the Invisible in the VisibleHeaney’s landscapes are palimpsests, surfaces inscribed, erased, and inscribed again, where new meanings emerge only through attentive excavation. In Bogland, he writes:

“Our pioneers keep striking

Inwards and downwards,

Every layer they strip

Seems camped on before.”

Here, space is not simply a backdrop for human action; it is an active agent in the formation of memory. The visible landscape conceals invisible histories — of violence, of toil, of ritual — that shape our sense of belonging.

This idea finds resonance in architectural thought. Kenneth Frampton, in his call for critical regionalism, warns against placelessness and urges designers to root their work in the cultural and topographic specificity of the site. Heaney’s poetry gives voice to this ethos, reminding us that every site is haunted by its own past, and that good design listens for these echoes rather than silencing them.

The architectural theorist and practitioner Peter Zumthor echoes this respect for the invisible in the visible: “The site is not simply a place where I build; it is part of what I build. The building does not stand on the ground, it emerges from the ground.” Heaney’s bogs and fields offer architects a model for how to engage with landscape as a living archive.

Kenneth FramptonTopography and the Ethics of Place-Making

Kenneth FramptonTopography and the Ethics of Place-MakingAt the heart of Heaney’s spatial poetics is an ethics of place-making. His work asks us to honour the integrity of the land, to recognise its layered meanings, and to design in dialogue with its memory. In The Tollund Man, he writes of the bog body:

“I will feel lost,

Unhappy and at home.”

This tension — between belonging and estrangement, between the known and the unknowable — defines his relationship with place. Heaney teaches us that to make a place ethically is to acknowledge these tensions, to design not for mastery over the land but for companionship with it. For architects, this means resisting the urge to overwrite the land with generic forms, and instead engaging in what Heaney might call a conversation with topography. It means allowing the shape of a hill, the course of a stream, or the memory of a field boundary to inform the shape and orientation of a building. It means seeing a place not as property, but as a partner. In the words of Glenn Murcutt: “We do not impose on the landscape; we work with it.”

Heaney’s vision of space as layered, storied, and morally charged offers a powerful counterpoint to the flattening tendencies of globalised design. His poetry asks architects to dig deeper, to see more, and to build with humility before the deep time of the land.

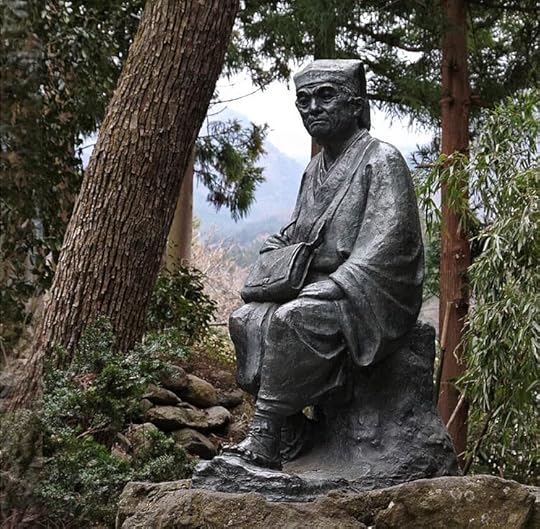

Poet #5: Matsuo Bashō and the Ephemeral JourneySpace as a Sequence of Moments

Poet #5: Matsuo Bashō and the Ephemeral JourneySpace as a Sequence of MomentsMatsuo Bashō, master of the haiku and of the poetic journey, invites us to experience space not as a static entity but as a sequence of moments, each fleeting, each charged with transience. His travel journals, like Oku no Hosomichi (something along the lines of The Narrow Road to the Deep North), trace paths through landscapes where space is continually revealed and redefined by the traveller’s passage.

For Bashō, space is not a fixed composition but an unfolding of encounters: the sudden opening of a view through mist, the shifting of light on water, the momentary alignment of stone, tree, and sky. This conception of space resonates with the idea of architecture not as object, but as experience, an architecture that emerges, as Bashō’s poems do, through time and movement.

Architects like Kengo Kuma echo this sensibility. Kuma writes: “We pursue an architecture that vanishes. An architecture that melts into the landscape.” Like Bashō’s path, Kuma’s architecture seeks not permanence, but presence, attuned to the rhythms of nature and the temporality of human life.

A statue to the poetThe Haiku as a Spatial Composition

A statue to the poetThe Haiku as a Spatial CompositionBashō’s haiku are themselves micro-architectures of space and time. With the utmost economy, they conjure entire worlds within seventeen syllables. Consider his famous haiku:

“An old pond,

*a frog jumps in,

the sound of water.”

Here, space unfolds through a sequence: the stillness of the pond, the leap of the frog, the ripple and sound that mark the moment’s passing. The haiku is not a snapshot but a choreography, a spatial composition that depends on what precedes and what follows, on silence and sound, on absence and presence.

This minimalist spatial poetics offers profound lessons for design. In architecture, as in haiku, what is left unsaid — the pause, the void, the interval — is as significant as what is articulated. And as much as this might escape us when translated in our Western languages, Tadao Ando captures this in his reflection: “I don’t believe architecture has to speak too much. It should remain silent and let nature in the guise of sunlight and wind speak.” Like the haiku, architecture can frame and heighten awareness of the transient, the subtle, the barely-there.

Tadao Ando’s architecture in NaoshimaTemporal Architecture: Learning from Impermanence

Tadao Ando’s architecture in NaoshimaTemporal Architecture: Learning from ImpermanenceBashō’s vision of space is inseparable from his deep embrace of impermanence, or mujō. His poetry celebrates the passing of the seasons, the weathering of buildings, the falling of blossoms. This attitude challenges the Western architectural obsession with durability and monumentality. Bashō’s lesson is that beauty and meaning arise precisely because things change and fade. In Oku no Hosomichi, Bashō reflects on the decayed ruins of past grandeur:

“The summer grasses—

All that remains

Of warriors’ dreams.”

The remains of castles and temples are not failures of permanence, but reminders of the natural cycles to which all human works belong. For architects, this suggests a practice that designs with time in mind, not to defy it, but to move with it. The patina of materials, the growth of moss, the erosion of stone: these are not defects, but part of architecture’s dialogue with the world. This idea resonates with the philosophy of wabi-sabi and with contemporary designers like Peter Zumthor, who is scarcely Japanese and still he writes:

“Buildings that have the qualities of age and time… they touch us because they bear witness to the life that has been lived within them.”

Bashō’s haiku, with their distilled temporality, remind architects to create spaces that are not frozen in time, but that invite and embody the passage of time. To build in Bashō’s spirit is to accept that architecture, like the journey, is always incomplete, always becoming.

Common ThreadsAcross cultures, eras, and languages, the poets we have explored — Emily Dickinson, Rainer Maria Rilke, Pablo Neruda, Seamus Heaney, and Matsuo Bashō — offer a vision of space that challenges, enriches, and ultimately transcends conventional architectural thinking. Though their voices differ, they share key insights that architects might find stimulating to heed.

Space as Lived Experience, Not Abstract FormEach of these poets teaches us that space is not a neutral container, a stage upon which life merely happens. Instead, space is something felt, inhabited, and made meaningful through memory, perception, and use. Dickinson’s small room expands through imagination; Rilke’s thresholds invite transformation; Neruda’s table becomes the altar of daily ritual; Heaney’s bog preserves the deep time of human histories; Bashō’s path reveals space as momentary and ever-changing.

This stands in stark contrast to an architectural tradition that has often privileged visual composition, geometric rigour, or iconic form. As Louis Kahn put it: “Architecture is the making of the world as it should be, not as it is.” But the poets remind us that architecture is not merely the art of creating what nature cannot, but the art of creating spaces in dialogue with nature, time, and the human condition.

The Value of Ambiguity, Silence, and the UnseenPoetic space is rarely totalizing or complete. It leaves room for the unknown, the incomplete, the ambiguous. Rilke’s houses are porous to angels and shadows; Heaney’s landscapes hold histories we can never fully uncover; Bashō’s spaces exist only in the instant of perception.

Architects can learn here the value of designing not only for clarity but for mystery. Peter Zumthor’s call for buildings that have “a beautiful silence about them” echoes the poet’s wisdom: space should not always shout; sometimes it should listen.

Materiality and Sensory RichnessWhere much contemporary architecture risks becoming dematerialised — relying on glass, steel, and abstract surfaces — the poets draw us back to the world of touch, scent, and sound. Neruda’s odes are hymns to grain, weight, and texture. Heaney’s soil and Bashō’s rain wet the hands and the feet. Dickinson’s room is felt in the hush of solitude.

This is an invitation for architects to engage all the senses in their design: to think about how a floor feels beneath bare feet, how a door handle greets the palm, how a space smells after rain.

Time as a Dimension of DesignFinally, these poets show us that space cannot be separated from time. Buildings are not fixed objects: they weather, they age, they are lived in and changed. Bashō’s haiku is architecture in miniature: a structure built to house a moment. Heaney’s bog is architecture in the deep time of geology and history. Dickinson’s room is a vessel for memory. In embracing impermanence, architects can move beyond the illusion of permanence toward designs that gracefully accommodate growth, decay, and renewal.