Word with a Past: Muckrackers

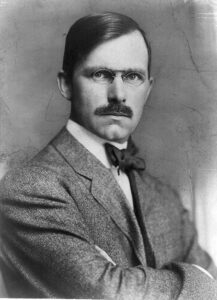

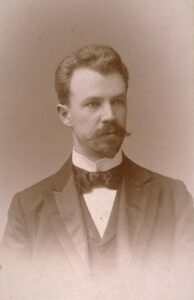

While I was writing about Rebecca Harding Davis (1831-1910), I started off thinking of her as a proto-muckraker, working a generation before people like Ray Stannard Baker (1870-1946),* Lincoln Steffens (1866-1936), Ida Tarbell (1857-1944) and Ida B. Wells (1862-1931). But the closer I looked, the more I realized that the realism for which she was known was not the same as the investigative reporting which earned the muckrakers their name. They exposed political and economic corruption–and related social hardships–that resulted from the growing power of big business in the Second Industrial Revolution. Corporate monopolies, political machines, unsafe working conditions, urban poverty, and child labor were all fair targets. Davis described the hardships, but she didn’t dig for the, well, muck.

I sadly abandoned several lovely but incorrect sentences about Davis, and then treated myself to a little rabbit-holing. Here are the high, or possible low, points:

The word muckrake entered English in 1366 as the name for a rake designed to collect and spread muck, referring to manure, not filth in general.John Bunyan was first the first to use the implement in a literary metaphor, noting in Pilgrim’s Progress that “The Man with the Muckrake could look no way but downward”—and that he consequently was unable to look up when offered a spiritual crown.Theodore Roosevelt used Bunyan’s words and imagery in a 1906 speech in which he exhorted the investigative journalists of his time to show moderation: “The men with the muck rakes are often indispensable to society; but only if they know when to stop raking the muck, and to look upward to the celestial crown above them, to the crowd of worthy endeavor. There are beautiful things above and round about them; and if they gradually grow to feel that the whole world is nothing but muck, their power of usefulness is gone.” (You can read the entire speech here . Personally, I think Roosevelt makes some good points.)Roosevelt did not mean the term as a compliment, but many of the journalists of the time embraced it.

Muckraking as a movement disappeared between 1910 and 1912. The need for journalists willing to look down and the stir the, ahem, muck, did not.

*Who also wrote work that was the antithesis of muckraking using the name David Grayson. As Grayson, he wrote books of personal essays with titles like Adventures in Contentment, Adventures in Friendship, and The Friendly Road. He not only took on a different name for these books, he created an entirely different persona. Baker was an Amherst family man; Grayson a well-read bachelor who left the city to live on a modest farm. (Think an intellectual version of the 1960s television comedy Green Acres,** minus the glamorous wife and, presumably, Arnold Ziffel, the pig.) Grayson had serious fans: they formed clubs named after him and called themselves Graysonians, claiming to be dedicated to the simple life. On the other hand, as Baker he won a Pulitzer for his biography of Woodrow Wilson. Best of both writing worlds?

**My apologies to any of you who now can’t get the theme song out of your head.