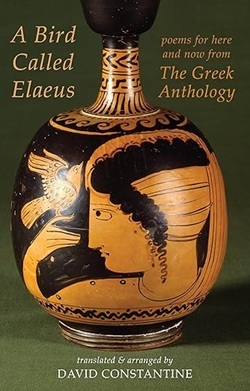

Review of A Bird Called Elaeus, by David Constantine, pub. Bloodaxe 2024

The thing about the Greek Anthology; it is universal in a way so much poetry aspires to be. It deals with universal human concerns, which is why it lends itself not just to straight translation but to re-making in other contexts. There is some of both here. Constantine’s translation of an epigram of Leonidas of Tarentum is fairly straight:

This here is Clito’s bit of a dwelling, this

The bit of land he sows, that there’s

His vineyard, that his wood, both scant. Nevertheless

Among these meagre ownings Clito’s clocked up eighty years.

This felt oddly familiar, and was, but not via Leonidas. I was recalling the Orkney poet Robert Rendall:

Look! This is Liza’s but and ben,

Wi’ screen o’ bourtrees tae the door,

Her stack o’ peats, her flag-roofed byre,

Her planticru abune the shore;

Yet ‘mang her hens and household gear

She’s brucked aboot for eighty year.

Constantine is himself a fine poet and his versions of the Anthology poets are as sensitive and effective as one might expect. The poets he has chosen are a personal selection. The predominance of Leonidas must be a personal preference, and understandable, because the man was such a superb epigrammatist that one wonders if there has ever been a better. Constantine also makes a point of foregrounding the female poets who are often overlooked, especially Anyte of Tegea, whose work also fits in with a thread of kindness to animals that runs through the selection – this concern for nature and our fellow creatures will resurface in the Coda, a section of his own poems inspired by the Anthology. Anyte was clearly an animal lover, and several of the Anthology poets express indignation at ill-treatment of horses or sympathy for injured dolphins, seen as friendly to man. Perhaps the most moving is Addaeus of Macedon, praising a grateful farmer:

When his labouring ox was worn out by old age and the furrows

Alcon, reverencing him for his service, led him not to the slaughter

But to a meadow of deep grass. There how this fellow creature

When Alcon strolls out to visit him at the hour of shadows

In grateful delight lifts up his head and bellows!

“This fellow creature” – we do not often think of the ancient world as a kindly place for other species, but some of the Greek anthology poets clearly had a sense of fellowship with them.

This kinship with animals is a major theme of the epigrams he has chosen. So are human relationships, often expressed in the sense of loss on the death of friends or kin, and the often troubled relationship between humans and their environment, especially the sea, on which so many Greeks found both a living and their death.

In the “Coda” we have a further development, wholly original poems constructed on the acknowledged model of the Anthology poems. Many are full of contained anger and sadness both at what we do to each other:

Laws of war

We too had laws of war: don’t poison wells

Don’t fell the olive trees (they take so long to grow)

Don’t bomb the schools, don’t bomb the hospitals …

Stranger seeking our monument, look around you.

and at what we do to the environment and to other creatures:

Albatross chick

Opened, this babe’s full stomach looks like a trove

Of bright things stowed away for an after-life.

What we cast on the waters is not the food of love.

Nothing will come of us for you but grief.

Perhaps the two most striking examples concern the death of children. In the main body of the work, he translates Zonas, being as universally relevant as any poet has ever been:

Dour ferryman, coming for the child Euphorion

When you hush your prow through the reeds and touch the shore

Be kind. His father, standing in the muddy shallows

Will hand him up the plank. Reach down, Charon

Bring him carefully on board. Those are his first sandals,

His pride and joy. But his footing in them is still unsure.

And then we have Constantine’s own take on a child in the aftermath of war:

Child After.

Over and done with. All gone.

She is too small to be left on the road alone.

Another day, another night, will nobody come?

Death will, a kindness, and take her home.

I found it interesting to compare Constantine’s versions with those of Dudley Fitts in his “Poems from the Greek Anthology” (1978). Fitts’s choice was often different, he translated many more humorous poems, but when he and Constantine translate the same poem, you couldn’t say one version was better than another, more that they have looked at the poem from slightly different angles. But that’s the Anthology for you: new to everyone who reads it and the proof that ancient models still say something to living poets. Genius can’t date.