How to Start Writing Your Novel (or Screenplay or Whatever)

Over the years I’ve received a lot of questions about the craft and business of fiction—including in a bunch of recent interviews I’ve done about my latest novel, The System—questions to which my responses have been unfortunately piecemeal. Rather than the ad hoc approach, recently I decided it might be more useful to more people if I offered some periodic thoughts here on Substack. So here we are.

If you find this video useful, let me know in the comments—there’s a ton more to say on the topic and if people enjoy it, I’ll make time to do more.

Here’s the video I mention in the talk: Andrew Stanton’s Clues to a Great Story.

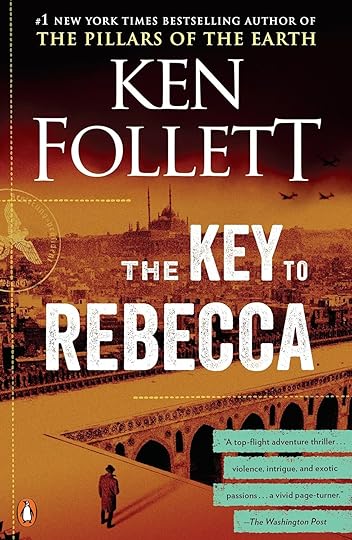

Okay. There are a lot of ways into this subject. Eventually we can talk about characters, structure, dialogue, and more—but for now I’m going to start by analyzing Ken Follett’s opening to his novel The Key to Rebecca, a terrific thriller that begins with the best example of opening craft I’ve ever read.

I’ve included the jacket copy below so you have context. Back in the day when I would teach writing workshops, I noticed that a fair number of students didn’t want to give context—“Just read it pure and unsullied, I don’t want you to be influenced by anything I might say,” they would tell me. My response was always, “We can do it anyway you want, but know that in the real world, no one ever reads a book or sees a movie without context. You never buy a book without knowing something about it; you never go to a movie without some notion of the movie that’s more specific than ‘It’s a movie.’ You’ve always been cued beforehand. So I recommend that rather than an unrealistic and artificial experiment, we do in practice what always happens in real life, instead.”

And now, on to The Key to Rebecca.

A brilliant and ruthless Nazi master agent is on the loose in Cairo. His mission is to send Rommel’s advancing army the secrets that will unlock the city’s doors. In all of Cairo, only two people can stop him. One is a down-on-his-luck English officer no one will listen to. The other is a vulnerable young Jewish girl…

The last camel collapsed at noon.

It was the five-year-old white bull he had bought in Gialo, the youngest and strongest of the three beasts, and the least ill-tempered: he liked the animal as much as a man could like a camel, which is to say that he hated it only a little.

They climbed the leeward side of a small hill, man and camel planting big clumsy feet in the inconstant sand, and at the top they stopped. They looked ahead, seeing nothing but another hillock to climb, and after that a thousand more, and it was as if the camel despaired at the thought. Its forelegs folded, then its rear went down, and it couched on top of the hill like a monument, staring across the empty desert with the indifference of the dying.

The man hauled on its nose rope. Its head came forward and its neck stretched out, but it would not get up. The man went behind and kicked its hindquarters as hard as he could, three or four times. Finally he took out a razor-sharp curved Bedouin knife with a narrow point and stabbed the camel's rump. Blood flowed from the wound but the camel did not even look around.

The man understood what was happening. The very tissues of the animal's body, starved of nourishment, had simply stopped working, like a machine that has run out of fuel. He had seen camels collapse like this on the outskirts of an oasis, surrounded by life-giving foliage which they ignored, lacking the energy to eat.

There were two more tricks he might have tried. One was to pour water into its nostrils until it began to drown; the other to light a fire under its hindquarters. He could not spare the water for one nor the firewood for the other, and besides neither method had a great chance of success.

It was time to stop, anyway. The sun was high and fierce. The long Saharan summer was beginning, and the midday temperature would reach 110 degrees in the shade.

Without unloading the camel, the man opened one of his bags and took out his tent. He looked around again, automatically: there was no shade or shelter in sight—one place was as bad as another. He pitched his tent beside the dying camel, there on top of the hillock.

He sat cross-legged in the open end of the tent to make his tea. He scraped level a small square of sand, arranged a few precious dry twigs in a pyramid and lit the fire. When the kettle boiled he made tea in the nomad fashion, pouring it from the pot into the cup, adding sugar, then returning it to the pot to infuse again, several times over. The resulting brew, very strong and rather treacly, was the most revivifying drink in the world.

The Heart of the Matter

- Barry Eisler's profile

- 3027 followers