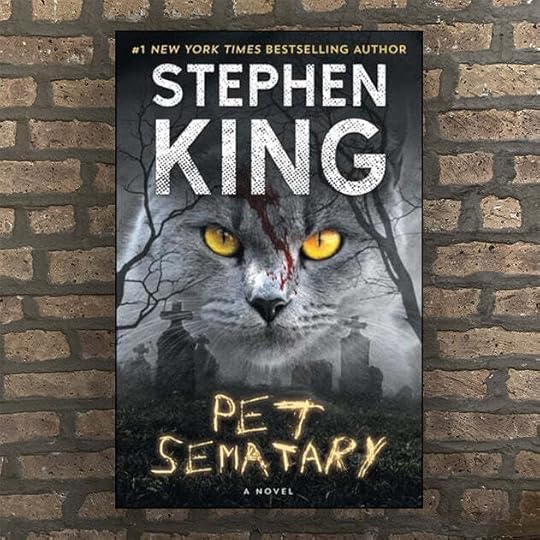

Pet Sematary Revisited

Knowing what a horror hound I am, last Halloween the book club at work asked me to recommend some suitable books for them to read. I’d previously been shocked at how few of them had ever read Sai King, and in a bid to remedy the situation recommended Pet Sematary. I’ve read it before, when I was a teenager, and wanted to see if my perceptions would be different now. When it first came out in 1983 I was barely even into double figures, and I didn’t even discover SK until my teens. This was probably one of the first of his books I ever read, if not THE first. I might have read it again at some point in the late nineties or early naughties but if I did, I can’t remember a lot about it. Not that that’s saying much. If you’d lived in nineties Britain, you’d know what I mean. This was the era of acid and Britpop.

I find Stephen King really easy to read, you just sort of fall into the story, the characters are relatable and he doesn’t try to reinvent the wheel. You pick up one of his books and the next thing you know you’ve read 50 pages. Which is just as well, as he has a bit of a reputation for waffling. Even the waffle, though, is kinda comforting, it’s like listening to Uncle Albert talk about the war, and it all helps shape the characters and the setting. I think because I’ve read him so much, I find his writing style very familiar. I know every quirk and idiosyncrasy. It’s like meeting an old friend for a pint. I’ve been off gallivanting and meeting lots of new people over the past few years (by that I mean making an effort to read other writers) so it feels good to get back to what I know. Like coming home. The version I read this time, a reprint published in 2000, includes an introduction where he talks about writing the book and then being so horrified by it that he stuck it in a drawer and only got it out again years later when he needed to fulfil a contract with his then-publisher. They always say that you should avoid harming children and animals in books because readers don’t like it. In Pet Sematary there’s plenty of both, along with some elder abuse for good measure. Well, it isn’t abuse as such. Old people die in it. They get moidered. But that isn’t saying much because children also die, as do students, regular folk and animals. Everyone dies, which ties into the fundamentals of the book.

One thing more clear to me now is that Pet Sematary is essentially a study in mortality. It’s about death, and the flip-side of death, which is, of course, life. The thought processes and actions of main characters, all at different stages of life, reflect this, meaning for an interesting dynamic. We have Luis and Rachel, in their thirties, their young kids Ellie and Gage, and the older generation represented by Jud and Norma Crandall. An exchange between the three groups quite early in the book not only demonstrates King’s insightfulness but also sets the tone for what follows. It’s Halloween night, and shortly before poor Norma has her heart attack, she gives the trick-or-treating Ellie an apple, which she drops. Ellie then says she doesn’t want a bruised apple, and Luis scolds her for being impolite. Norma then turns the tables and scolds him, reminding him that ‘only children tell the whole truth,’ the implication being, of course, that adults don’t. Harsh truths, and how people deal with them (or don’t) are integral to the story. How a parent would feel about an outsider undermining him in front of his offspring is another sub-plot, tantalisingly unexplored by SK. In this instance, anyway.

Something else that took on added weight is Jud’s reasoning for taking Luis to the place beyond the Pet Sematary even though he knew Church the cat would come back changed. The assumption was at first that he had done it because he felt endebted to Louis for saving Norma’s life. Then, he said he did it to teach little Ellie that sometimes dead is better, before finally admitting that he did it because he wanted to share the secret he was privy to (“You make up reasons, they seem like good reasons, but mostly you do it because you want to”). He was compelled to share the secret. Whether this was a damning indictment of human nature (Don’t we all love to share secrets?) or whether there was something deeper at work, is left to the reader’s imagination. The implication is that the Pet Sematary itself somehow reached out and influenced events.

In the book club discussion, it was agreed that there are many different kinds of horror; there’s the supernatural kind, the evil that men (or women) do to each other, then there’s the kind where terrible shit just happens. Accidents, natural disasters, survival situations, that kind of thing. It’s all horrific. Though Pet Sematary definitely has supernatural elements, given the prophetic dreams, the Indian burial ground, and people coming back from the dead, it’s more about that last category. It’s about the fragility of life, and how it likes to kick you in the arse every now and again. There are lessons to be found in this book, lessons that went completely over my head when I read it the first time. One more thing that has more resonance now is when Louis Creed quotes the Ramones’ Blitzkrieg Bop (“Hey ho, let’s go!”), which he does numerous times throughout the book. It makes you wonder whether they were being earmarked to do the soundtrack even while SK was writing the book, or whether that line was inserted later as one of his infamous Easter eggs.

Since editing other people’s work has been part of my day job I have become hypersensitive to bad habits. After a while, they stand out a mile. One of my pet hates is repetition, where writers use the same word, or words, repeatedly. I never noticed it with SK before, but in Pet Sematary a lot of people laugh until they cry. In the first half, anyway. There isn’t too much laughing in the second half. There’s a section around the midway point where it’s all happy families and Gage and Louis are flying a kite (Flyne, Daddy!) and even if you haven’t read it before you just know SK is setting you up for something. And when it hits, its brutal, man. BROO-TAL.

In the aftermath, the same suggestion that the Pet Sematary, or, more precisely, the Micmac burial ground that lies beyond it, might have the power to influence outside events to its liking is made again when the driver responsible for the carnage admits being clean and sober at the time of the accident, but was speeding because, “When he got to Ludlow he just felt like putting the pedal to the metal. He said he didn’t even know why.”

At its core, Pet Sematary raises an interesting ethical dilemma; if one of your loved ones died and you had the ability to bring them back, even though you knew they might come back changed, would you still do it?

Let’s face it, most of us probably would.

Like all of us, Louis Creed is deeply flawed. He is a weak man, though at the same time strong. He knows right from wrong, and he knows where the line is. But he is more than prepared to cross it, ostensibly to serve and protect his family. But dig a little deeper (pun intended) and you can see his actions are driven by selfishness rather than selflessness. He just wants things back the way they were because he preferred them that way.

I think sometimes we all kid ourselves that the things we do are for other people’s benefit when in reality we do it meet our own needs. Take, for example, people who donate their time or money to charity. Good on them, right? But ask yourself, do they really care about that particular charity? Or are they donating just because it makes them feel good? You might argue that it doesn’t matter. But if you value honesty and integrity, maybe it does. Of course, the other option is that Louis really had no choice in proceedings. He was always going to do what he did because that was what the force connected to the Pet Sematary/Micmac burial ground wanted him to do.

I can confirm that even after repeated readings, and even when you know it’s coming, that ending still packs a wallop.