Natalia Ginzburg and some lessons in design

What does Natalia Ginzburg, an Italian novelist of quiet prose and domestic landscapes, have to do with design? On the surface, little: she did not theorise objects or urban space, nor did she work alongside architects or engineers. Her worlds were ones of cramped kitchens, failed marriages, broken relationships, and political grief. And yet, these same qualities — restraint, attentiveness, the search for meaning in the everyday — offer profound lessons for the contemporary designer.

Design education today often centres on visibility, disruption, and — when it’s done right — measurable innovation. Whether in product development, UX/UI, or architecture, the designer is expected to deliver solutions that are efficient, elegant, and user-friendly but such expectations, and a certain superomistic approach to the designer as The One Who Understands The World, often obscure the slow, ethical labor of understanding what people feel, how they live, and why they resist change. In this gap — between functionality and meaning — Ginzburg becomes an unexpected guide.

Born in 1916 and shaped by fascism, exile, motherhood, and grief, Ginzburg cultivated a writing voice that was deliberately unspectacular. She wrote as if overheard, using language that was blunt, affective, and unadorned. It is precisely this anti-rhetorical stance that makes her valuable to design, a field that increasingly recognises the importance of humility, empathy, and storytelling.

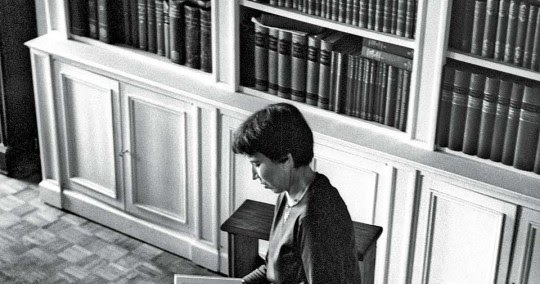

Natalia Ginzburg

Natalia GinzburgReading Ginzburg, we are reminded of what lies beneath function: the habits, contradictions, and rituals of everyday life. Her texts capture the tacit systems people design for themselves: kitchen tables as negotiation sites, domestic routines as ways of coping with disorder, relationships as fragile structures held together by repetition rather than clarity. In this way, her work parallels the work of design: she gives form to need, voice to context, and shape to the invisible.

Beyond literature, Ginzburg has become a touchstone in feminist thought, narrative ethics, and social history. Her insistence on narrating “small lives” against the backdrop of political collapse offers a critical model for designers interested in social impact, inclusion, and cultural memory. She teaches us that design is not just about making, but about witnessing. Not just solving, but listening.

In proposing Ginzburg as required reading for designers, this article does not seek to stretch her work into metaphor, nor to treat literature as decoration for theory. Instead, I’m arguing that her way of looking — attentive, relational, and unflinchingly honest — is itself a form of design literacy. In her margins, we find what the centre often forgets: that good design begins not in the blueprint, but in the kitchen, the silence, the story.

2. The Grammar of Everyday Life: Writing as DesignNatalia Ginzburg’s prose has often been praised as spare, restrained, even ascetic. Yet this economy is not a stylistic quirk but an ethical stance. Her writing, like good design, works through omission rather than excess: she removes clutter not to impress with elegance, but to preserve the truth of experience. Ginzburg assembles language with the precision and intentionality of someone sketching a schematic for human emotion.

“I believe that we must not tamper with the truth; we must not edit it, decorate it or twist it. We must accept it as it is, if we want it to be of any use.”

— Natalia Ginzburg, My Craft (often published in English as The Little Virtues)

This sentence could easily be pasted onto the wall of a UX design studio. In an era where clarity, usability, and ethical communication are prized across product, interaction, and service design, Ginzburg’s commitment to honesty and transparency resonates powerfully. She models what Don Norman describes in The Design of Everyday Things as “affordances”: clear cues in design that suggest how something should be used. Ginzburg’s writing is full of such affordances. It does not demand interpretation through metaphor or excess; it invites use, like a well-placed handle or a readable label.

Consider the layout of a Muji product, a Japanese design brand renowned for its minimalist aesthetic: a toothbrush with no branding, a desk lamp with no embellishment, and a kitchen timer reduced to its most essential controls. These are not “boring” designs: they are honest ones. Likewise, Ginzburg’s prose seems to retreat so that life can come forward. Her short story “La madre” (The Mother) ends with an ordinary phrase — “Poi non venne più” (Then she didn’t come anymore) — that lands like a punch. There is no crescendo, no flourish. Just absence, rendered exact.

This capacity for understatement finds strong echoes in UX writing principles. As Kinneret Yifrah argues in Microcopy: The Complete Guide, good interface writing avoids drawing attention to itself. It guides, supports, and reassures users in moments of uncertainty. Ginzburg does the same. In Lessico famigliare (Family Lexicon), she writes something along the lines of:

“We were five children. We lived in a large, dark, and noisy apartment. We were always shouting.”

These are not evocative metaphors or poetic abstractions but facts, delivered in rhythm, calibrated in tone. Yet within their simplicity lies a world of tension, of constraint, of joy and fatigue. This is information architecture disguised as memoir.

Her technique parallels what service designers call touchpoint choreography. The emotional experience of a service — waiting at a post office, filling out a tax form, booking a medical appointment — is not defined by any single moment, but by the accumulation of small, often invisible, interactions. Ginzburg teaches designers to attend to these. In Caro Michele, for example, the exchange of letters between a mother and her absent son is built on minutiae: groceries, stomach aches, a change in the weather. But these small data points aggregate into an emotional map of disconnection, anxiety, and love. It is design thinking applied to relational life.

Similarly, Jenny Odell in How to Do Nothing advocates for a politics of attention that resists the noise of capitalist productivity. Ginzburg shares this orientation decades earlier. Her work forces us to slow down, to notice the unspectacular that Odell calls “the chorus of the nonhuman.” In Ginzburg’s case, the chorus is domestic: saucepans, doors, the sound of someone breathing in the next room. It is the territory from which designers, especially those working in the domestic or social sphere, must learn to draw meaning.

Even the way Ginzburg structures her narratives offers a design model. She eschews traditional plot arcs for modular, repeatable sequences: conversations, habits, domestic choreography. One might think of Charles and Ray Eames, whose documentary Powers of Ten (1977) frames experience through a series of zooms, each moment nested within a broader system. Ginzburg too zooms in, not to aggrandise, but to clarify. She shows that meaning is not something designers insert into a system; it is something they reveal by carefully observing its existing grammar.

“Sometimes our own words aren’t really ours. They’re just echoes. Echoes of someone else’s words.”

— Lessico famigliare

This observation is as true for designers as for narrators. The materials we work with — language, space, form — carry with them histories, associations, and expectations. Ginzburg helps us listen to these echoes and choose what to pass on, what to reframe, and what to leave behind.

In sum, Ginzburg’s minimalist style is not merely a matter of taste: it is a model of design thinking grounded in restraint, respect, and radical clarity. She shows us that the ordinary, when attended to with precision and care, is not the opposite of the innovative: it is its grounding condition. She teaches designers to stop striving for the novel and start noticing what is already there.

3. Designing for Others: Empathy, Care, and the Relational GazeDesign is, at its most ethical, an act of care. It begins with the recognition that others exist: others with needs, constraints, contradictions, and desires that do not necessarily mirror our own. Few writers have captured this recognition more consistently than Natalia Ginzburg. Her entire literary project is built on paying close, difficult, and sometimes painful attention to others, especially when those others are elusive, annoying, or slipping away.

Ginzburg writes to inhabit the spaces alongside her characters as the only way to really define and understand them: her stories often unfold in the claustrophobic domestic environments of mid-century Italy — shared apartments, narrow kitchens, tight stairwells — where the only architecture is relational. Her protagonists seldom grow through self-actualisation; instead they grow, or collapse, in proximity to others. This lens is crucial for designers today, especially those engaged in social design, community-centred design, or participatory urbanism, where the success of a project often depends less on individual creativity than on relational intelligence.

“We are never alone in our pain or our joy; we are always surrounded by others, by their lives and their feelings, even when we think we are most isolated.”

— Natalia Ginzburg, My Craft

This sentiment offers a rebuke to individualistic narratives in both literature and design. Ginzburg’s people are not heroes. They are caretakers, in-laws, abandoned wives, bored children. The power of her work lies in its capacity to stay with the mundane without reducing it to cliché. She sketches communities in tension — marked by power imbalances, generational wounds, and political failure — but never without affection. Her gaze is relational, and for designers working within communities, that is everything.

Designers often turn to empathy maps or personas to frame user experiences, but these tools risk flattening lived complexity into digestible insights, and are getting less and less popular as they show their inadequacy to capture complexity. Ginzburg resists that simplification. In Caro Michele, the mother writes to her distant son with a mix of guilt, irritation, longing, and self-deception, sometimes all in the same paragraph. That emotional messiness is data, too, if designers are willing to listen for it. Her work models what Sara Ahmed might call an affective archive: a dense layering of emotions, gestures, and repetitions that reveal how people experience power, care, and abandonment.

This nuanced emotional landscape has profound implications for participatory practices. In co-design workshops or community engagement sessions, practitioners often enter with tools for listening — sticky notes, post-its, exercises in storytelling — but what’s harder is to stay with discomfort, to resist the urge to “solve” people’s problems on their behalf. Ginzburg teaches that real care begins not with the question What can I do for you?, but with the question Can I bear witness to what you are already living?

Natalia Ginzburg

Natalia GinzburgVisual designer and educator Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, a pioneer of feminist design, often insists that the designer’s job is not to impose meaning, but to build platforms through which people can express their own. Her iconic Pink poster project (1973), which invited anonymous contributions from women about the colour pink, mirrors Ginzburg’s instinct: to collect the fragmented expressions of others and make their logic visible. In Lessico famigliare, Ginzburg does just this, curating the personal vocabularies of her family, not to memorialise them, but to show how shared language can be a form of intimacy and exclusion at once.

“The words we used… belonged only to us, and when we repeated them, we believed we were saying something important.”

— Lessico famigliare

This attention to private language mirrors what service designers observe in tight-knit user groups: forms of interaction that are coded, intuitive, and emotionally significant. Whether it’s the slang used among hospital staff, the unspoken rituals in a neighbourhood café, or the gestures exchanged by passengers on a bus, these micro-rituals are forms of relational infrastructure. Ginzburg uncovers them in writing; designers must do so in the field.

Furthermore, her ethics of representation — never sentimental, never exploitative — should be required reading for anyone engaged in the politics of design. When we tell a user’s story in a case study, when we cite a community member in a pitch, when we quote an interviewee on a slide, what responsibility do we carry? Ginzburg, who wrote often about the people she loved and lost, refused to idealise them. She offered their contradictions alongside their virtues, their small betrayals alongside their sacrifices.

This is the emotional precision that social design demands. As Ezio Manzini notes in Design, When Everybody Designs, the designer is now a facilitator of “enabling solutions” that emerge from communities themselves. To do this well requires not just tools but a disposition—one that Ginzburg exemplifies: humble, attentive, unafraid of ambiguity.

In sum, Ginzburg’s body of work offers a model for design practice grounded in witnessing rather than problem-solving, relational attentiveness over visionary leadership, and emotional precision in place of emotional packaging. She reminds us that the most transformative interventions often happen not through grand gestures, but through acts of careful noticing: a hand on a shoulder, a phrase half-repeated, a silence held between people.

4. Form, Resistance, and Silence: A Politics of DesignIn an age dominated by noise — visual, verbal, digital — resistance often takes the form of silence. Of withholding. Of choosing not to amplify. Natalia Ginzburg, in both her literary style and political positioning, understood this intuitively: her writing does not shout; it lingers. It does not assert, it witnesses. In its quietness, in its anti-rhetorical form, it becomes an act of refusal. For designers grappling with excess, spectacle, and urgency, Ginzburg’s practice offers a model of resistance through form.

“I write in a flat voice, a voice that leaves things out, because life itself is flat and leaves things out.”

— Natalia Ginzburg, My Craft

This is not self-deprecation but strategy. Ginzburg’s stylistic flatness is a refusal to perform, to embellish, to please, a politics of minimal presence, especially potent for a woman writing under and after fascism. Just as resistance movements often take form in silence, secrecy, or coded speech, her writing holds space for the unsaid. This form of communication — what Susan Sontag called “writing against interpretation” — has direct relevance to critical design, speculative design, and any practice that challenges dominant narratives by withholding easy answers.

Susan Sontag

Susan SontagTake Lessico famigliare, for instance, which is rightfully considered Ginzburg’s most significant and accessible work. Beneath its fragmented anecdotes and remembered phrases is a political story — of anti-fascist struggle, persecution, exile, the assassination of Leone Ginzburg — told almost entirely without explicit commentary. The political is embedded in the domestic, smuggled through speech, suggestion, silence. This approach mirrors how critical design practitioners like Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby craft speculative artefacts: not to explain, but to provoke reflection. Just as Ginzburg’s silence is a provocation.

Fiona Raby

Fiona RabySilence in design is often misunderstood as lack. But in fact, designing with absence can be one of the most powerful communicative strategies. Consider the white space in a Yoko Ono instruction piece, or the subtractive minimalism of a Tadao Ando chapel. These are not neutral or serene gestures but forms of refusal. They force the viewer or user to do more, to participate, to project. Ginzburg, too, demands an interpretive labour of the domestic. She writes, but does not explain. She describes, but does not justify. Her silences ask the reader to fill in the emotional and political gaps, thereby creating an ethical bond of participation.

In design, this mirrors constraint-based practices, where limits become generative. Working with limited materials, restrictive budgets, inaccessible sites, or institutional obstacles, designers often produce their most creative work under pressure. Ginzburg’s work is forged in constraint: political censorship, grief, the banal logistics of motherhood, the expectation of silence from women. But like the architect Anne Lacaton, who famously declared “Never demolish,” Ginzburg makes something from what remains. She builds form out of loss.

“After a death, the days go on as before, but nothing is the same anymore.”

— Caro MicheleAnne Lacation

This paradox — of permanence within loss — is a key concept for designers working in memorialization, disaster recovery, or transitional urbanism. How do we design for grief? For rupture? For that which can no longer be directly named? Ginzburg offers no answers, only blueprints for how to persist in the wake of silence. Her refusal of closure, her resistance to arc or redemption, has deep implications for counter-hegemonic design. Where mainstream design often seeks to solve, conclude, streamline, Ginzburg remains with the unresolved. This makes her an ally to those working on the margins — migrant communities, disenfranchised populations, Indigenous designers — who resist being packaged into digestible narratives for policy or publicity.

Even in her essays, Ginzburg deploys rhetorical silence: long, flat paragraphs with no formal transitions; stories that begin mid-thought and end without catharsis. These are structural refusals. They mirror the work of feminist architects and spatial practitioners like Jane Rendell or Doina Petrescu, who speak of “critical spatial practice” as a method of occupying liminal, incomplete, or contested spaces. Ginzburg’s texts are these kinds of spaces: unfinished, resistant to enclosure, structured around omission.

This ethic — of restraint, refusal, and radical silence — should be central to any politics of design. It teaches us that form is not neutral; it always expresses values. And sometimes, the most political choice a designer can make is to leave something out: to not speak for the user, to not polish the story, to not fill the space. In doing so, we make room for others not just as subjects, but as co-authors.

5. Biography, Memory, and the Built EnvironmentNatalia Ginzburg never wrote explicitly about architecture, but few writers have mapped the emotional topography of domestic space as intimately as she did. Her narratives unfold not just in time, but in places inhabited, abandoned, returned to, or remembered. Rooms are not neutral containers but protagonists, as kitchens carry the weight of unsaid resentments, hallways are conduits of surveillance and avoidance, shared apartments reflect political alliances and personal betrayals. In Ginzburg’s work, the home becomes the architecture of biography, the stage on which memory, identity, and transformation are continually rehearsed.

“That house remembers everything, holds all our voices, even those who are no longer here.”

— Lessico famigliare

Her approach captures what spatial designers, urbanists, and architects have long recognised: that built environments store affect. They are archives of experience, holding onto gestures, silences, even grief. Ginzburg’s homes are not abstract or symbolic; they are stubbornly real, marked by the messiness of life, and yet they carry emotional geometries that spatial design must reckon with: how a room’s proportions can generate tension, how furniture can enforce roles, how space can reinforce or resist memory.

Her autobiographical strategy — what we might call a narrative mapping of lived space — bears striking resemblance to practices in architectural phenomenology and heritage conservation. Think of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, which explores how attics, cellars, and drawers shape the contours of interior consciousness. Ginzburg’s attics and kitchens do the same, but they are never abstractions. They are layered with people, crumbs, muttered phrases. They are lived spaces, thick with repetition, rupture, and unresolved history.

Gaston Bachelard

Gaston BachelardIn The City and the House, a novel told entirely through letters, Ginzburg charts how place mediates relationships. Cities and houses are not neutral settings but living forces: Paris, Rome, the countryside, each produces different intimacies, different forms of alienation. The house becomes a main character, not only in its architecture but in its role as a vessel for longing, exile, and attachment. This resonates with how urban storytelling is approached in disciplines like placemaking and civic design, where memory is embedded in both physical structures and the narratives that surround them.

Projects such as Massimo Scolari’s The Theatre of Architecture, Joan Ockman’s Out of Ground Zero, or Forensic Architecture’s investigations similarly frame buildings as witnesses, not static objects but actors within history. Ginzburg, through quieter means, does the same: her writing turns the house into an interlocutor, and her biographies don’t just to tell about a life, but to render the built environment as a companion to loss, joy, or betrayal.

This is not nostalgia; it’s spatial indexing. Memory in Ginzburg is not linear but properly architectural. It returns in loops, tethered to objects and thresholds: a cracked wall, a broken lamp, the smell of a stairwell. These are the same anchors that interior designers, curators, and urban ethnographers work with when trying to preserve or reimagine a space’s identity: in post-conflict architecture, for instance, designing around memory often involves more than plaques or reconstructions, but listening to the everyday remnants people associate with presence and absence. Ginzburg’s stories offer that attentiveness, in narrative form.

Her approach to autobiography also challenges the division between personal and public memory. While writing her family’s story in Lessico famigliare, she documents a collective experience: of fascism, resistance, displacement. The apartment in via Pallamaglio becomes not only a private home but a microcosm of historical forces. This echoes how heritage studies now think about domestic spaces, not just as sites of personal memory but as arenas where political histories are enacted and contested. In contemporary urban regeneration projects, especially in historic neighborhoods, this lesson is crucial. Too often, design intervenes without understanding the narrative infrastructure already embedded in place. Ginzburg teaches us that the stories people tell about their homes — the things they say, repeat, forget — are design materials. Memory isn’t soft data; it is structural. It shapes how people move, what they protect, how they orient themselves to the future.

This is where Ginzburg intersects with the work of Lina Bo Bardi, the Italian-Brazilian architect who believed that design must respect the social fabric already in place. Bo Bardi’s buildings — like the SESC Pompéia in São Paulo — preserve traces of their past use, allow for adaptation, and refuse monumentalism. Ginzburg does the same with text. She preserves the cracks. She allows the ordinary to speak.

Lina Bo Bardi

Lina Bo BardiIn the end, Ginzburg’s autobiographical spaces offer a method for reading and designing space as lived, remembered, and relational. They teach us that architecture is not only what we build, but what we carry. That the city is not only a structure, but a memory system. And that biography, when told through space, becomes not self-expression but shared infrastructure.

6. Teaching Ginzburg to Designers: a Practical CompendiumIf Natalia Ginzburg should be required reading for designers, what does it look like to teach her, not as an add-on to the syllabus, but as a structural element of design education? Integrating Ginzburg into a design curriculum is not about turning literature into a case study or poeticizing the design process, but about cultivating a disposition: attentive, honest, and grounded in the complex dynamics of human life. Her writing becomes not content but method, not subject matter but lens.

Contemporary design teaching strategies, especially within human-centered or speculative design, is increasingly aware of its limitations. The prevailing design thinking model — typically structured around problem definition, ideation, prototyping, and iteration — risks instrumentalizing empathy, aestheticizing complexity, and prioritizing innovation over care. Ginzburg’s narrative techniques stands as a counterweight: she teaches slowness, precision, ethical ambivalence, refuses to solve or optimize. She pays attention instead. That is the beginning of good design.

“We are adult because we have behind us the silent presence of the dead, whom we ask to judge our current actions and from whom we ask forgiveness for past offences: we should like to uproot from our past so many cruel words, so many cruel acts that we committed when, though we feared death, we did not know — we had not yet understood — how irreparable, how irremediable, death is: we are adult because of the silent answers, because of all the silent forgiveness of the dead which we carry within us.”

— My Craft