I’d send my love to all the kids who feel like weirdos.

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of existing?

Kathryn Mockler: What is your first memory of existing?Kate Gies: My first fully formed memory is the day I used a toilet for the first time on my own. I’ll spare you some of the specifics, but afterward, I called my parents in and they stood around the toilet and clapped for me and my little floating turd. I was then awarded with a trip to Tim Hortons and a chocolate éclair. I remember being so proud of myself, and also thinking how the éclair looked similar to the turd I’d made.

KM What is your first memory of being creative?KG: I don’t ever remember a time I was not drawn to colour, words, and music.

I remember being very young and going into a neighbour’s garden, pulling out her own flowers to make a colourful bouquet, and then ringing the doorbell to give it to her. Despite me ruining her garden, she’d always give me a mint. My mother had a talk with me about it and I started drawing her pictures to get my mint. After that, I drew pictures for everybody. I remember a cello and bow I drew that stayed on my musician uncle’s fridge for many years.

In addition to flower arranging and drawing, I made up songs and recorded them on my tape player. I also made up dances to Madonna songs and performed for babysitters.

Perhaps not surprisingly, I didn’t have a lot of friends when I was really young and I was set up with a girl whose parents were friends with my parents (she didn’t have a lot of friends either). We wrote plays together and presented them to our parents. Some of my favourite creative memories come from that friendship.

KM: What is the best or worst dream you ever had?KG: A long-time favourite dream of mine is from when I was thirteen. At the time, I was bullied by a group of boys in my class after showing up to school with a large bandage wrapped around my head (a souvenir from a surgery). In the dream, I was part of a secret society that met under a sun-drenched willow tree. The boys who bullied me were also part of the secret society. Under the willow tree, we’d eat fistfuls of All-Bran that would make us “high”. (To note: I didn’t have a concept of what “being high” was like, as I wasn’t cool enough for anyone to offer me drugs in real life, but in the dream, it made us all huddle in a giant group hug.) Anyway, I loved that dream. I’d flick back to the memory of it for years, the warm feeling of “being high” under the willow tree, the sun glittering on my face, enveloped in the arms of the kids who hated me most.

KM: What is your favourite or significant coincidence story to tell?KG: I’ve had many moments of synchronicity throughout my life. For me, they are a beautiful reminder that there is something big connecting us all to each other.

Two examples:

1. I teach creative writing in a program for people with mental health and addiction issues. About ten years ago, one of my students mentioned a poet he liked who’d just written an e-book about his mental health journey. Two days later, I shared a bathroom with that poet at a week-long writing retreat. We ended up dating on and off for two years and he became a significant part of my own life journey.

2. I took a writing and meditation course with a beautiful instructor who left a big impact on me. A few years later, I attended a conference for work on the importance of meditation in education. There were thousands of participants spread over multiple dorms across the campus. In my dorm, I shared a bathroom with the person in the room next to me (the bathroom connected our rooms together). On the first night, I opened the bathroom door at the same time as the person in the other room opened the bathroom door from her end. And yes, it was my writing and meditation teacher.

KM: Do you have a preferred emotion to experience? What is it and why? Or is there an emotion that you detest having and why?KG: I’ve been off chocolate since I was twelve, as it causes me migraines. Once, while riding passenger side on a coastal drive through Florida, I ate a red-velvet cupcake (not realizing that it had chocolate in it). What resulted was a calm that spread through me like light. Not a quiet calm, but the calm one gets when neurons explode in perfect symphony. With the ocean beside me, and the orange-red bleed of a late afternoon sun, everything around me felt illuminated, like a childhood memory of summer. That was a good feeling.

My least favourite feeling is definitely shame. This has been a big one throughout my life and I’m working hard at eliminating it where I can. For me, shame feels like a belly full of glass—heavy, sharp, and immobilizing. It’s such a damaging emotion.

KM: Can you recount a time (that you're willing to share) when you were embarrassed?KG: As someone who is hard of hearing, I’ve many moments of embarrassment. Often mis-hearing words, or having to ask people to repeat themselves many times until it’s super awkward socially. When I was young, gym class was the worst, as the teacher and students kept moving around and it was hard to hear instructions. I have a story in my memoir about playing Ring Around the Rosey and falling too soon, dragging all the kids down with me.

Two other embarrassing moments unrelated to hearing:

1. In eighth grade, we were in an assembly where I had to read something in front of the school. I had a dentist appointment that day and my mother had given me instructions to meet her in front of the school at a specific time. I thought I’d have time to do my reading, but realized just as I was walking up the steps to the stage that it was time to meet my mother. I got up on stage, leaned into the mic, and instead of doing the 2-minute reading, I said “I have to go to the dentist”. I then promptly exited stage right to a loud and sarcastic applause.

2. In my mid-twenties, I was just finishing up a job interview at York University that I’d thought had gone really well. The HR person walked me out to the elevator. She leaned to put down her suitcase and I thought she was going in for a hug. So I hugged her. It wasn’t until I felt her body stiffening that I realized, she had, in fact, not leaned in for a hug.

KM: What advice would you give to your younger self? Your younger self could be you at any age.KG: Don’t, under any circumstances, hug the HR person at a job interview.

KM: Do you believe in ghosts? Why or why not?KG: Yes. I haven’t had a personal experience with a traditionally conceptualized ghost, but I’ve definitely felt the essence of people after they’ve passed.

My Oma passed away very suddenly when I was eighteen. She was truly an amazing woman. She was orphaned at age nine and became a wife and mother in her late teens. At age fifty, she decided she wanted to learn to paint and by sixty, she was restoring AY Jacksons and other famous Canadian painters. She was generous and brilliant and humble. When I was a little kid, I was terrified of the large moths that showed up at the cottage we used to rent in the summer. I found their frenetic enthusiasm for light very disturbing. My Oma took it upon herself to help me through this fear. She walked me out to the trees and I remember her guiding my finger over the velvet-soft nest of the moths. She told me all sorts of interesting facts about moths, and effectively turned my fear into fascination. Many years later, in what would be our last conversation, I reminded my Oma of this gift she gave me. We laughed and reminisced about our times at the cottage. Three days later, she died of a brain aneurism. I was devastated. One night, early in my grief, a large moth found its way into my bedroom. Instead of flying into the light of the lamp, it stayed still on the wall beside my bed. I swear I could feel the soft energy of my Oma in this moth.

KM: If you could send your love to anyone, who would it be and why?KG: I’d send my love to all the kids who feel like weirdos. The kids who feel they need to hide parts of themselves to be loved. I see you. You’re cooler than you think, I promise. And those parts of yourself you feel you need to hide are the very parts that make you most human, and by extension, most loveable.

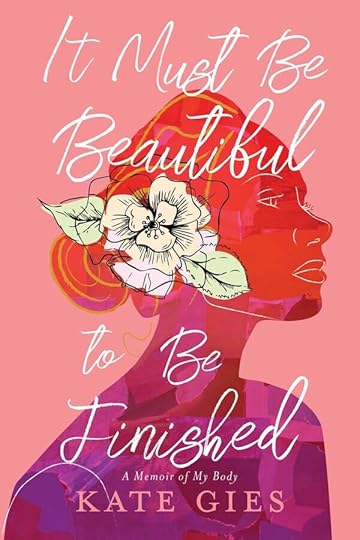

KM: Tell me about your latest book.KG: My book, It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished: A Memoir of My Body, is about my experiences growing up missing an ear, the well-intentioned violence of the medical system intent on “fixing” me, and the booms and echoes of the body shame I’ve carried throughout my life. It’s a story about coming of age in the 90’s, and all the gross and insidious messages girls received about their bodies at that time. It’s about coming of age again, much later in life, and learning to fully inhabit a body I never believed was mine to own.

Kate Gies is a writer and educator living in Toronto. She teaches creative nonfiction and expressive arts at George Brown College. Her fiction, nonfiction, and poetry have been published in The Malahat Review, The Humber Literary Review, Hobart, Minola Review, and The Conium Review. She was a finalist for the CBC Nonfiction Prize, and her essay “Foreign Bodies” (excerpted from It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished) will be included in the forthcoming Best Canadian Essays anthology from Biblioasis. Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished: A Memoir of My Body

by Kate GiesSimon Schuster, 2025

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published

It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished: A Memoir of My Body

by Kate GiesSimon Schuster, 2025It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished

A raw, beautiful memoir of a girl born missing an ear, a medical system insistent on saving her from herself, and our culture’s desire to “fix” bodies.

When Kate Gies was four years old, a plastic surgeon pressed a synthetic ear to the right side of her head and pulled out a mirror. He told her he could make her “whole”—could make her “right”—and she believed him. From the age of four to thirteen, she underwent fourteen surgeries, including skin and bone grafts, to craft the appearance of an outer ear. Many of the surgeries failed, leaving permanent damage to her body.

In short, lyrical vignettes, Kate writes about how her “disfigured” body was scrutinized, pathologized, and even weaponized. She describes the physical and psychic trauma of medical intervention and its effects on her sense of self, first as a child needing to be fixed and, later, as a teenager and adult navigating the complex expectations and dangers of being a woman.

It Must Be Beautiful to Be Finished is the story of a girl desperately trying to have a body that makes her acceptable and of a woman learning to own a body she has never felt was hers to define. In an age of speaking out about the abuse of marginalized bodies, this memoir takes a hard look at the role of the medical system in body oppression and trauma.

Bluesky | Instagram | Archive | Contributors | Subscribe | About SMLTA