Prophets of the Silver Screen: 10 Sci-Fi Movie Predictions That Became Our Reality

Science fiction cinema has long held a hallowed space in our culture as a window into tomorrow, a genre where imaginative minds dare to envision the worlds we might one day inhabit. Yet, to label these films as mere fortune-tellers is to miss their profound, often startlingly direct role in shaping the very future they depict. The silver screen has functioned not as a passive crystal ball, but as a vibrant, chaotic, and astonishingly effective cultural research and development lab. It is a space where future technologies are prototyped in the public imagination, where their ethical and societal implications are debated before the first circuit is soldered, and where a visual and conceptual language is forged for the innovators who will eventually turn fiction into fact.

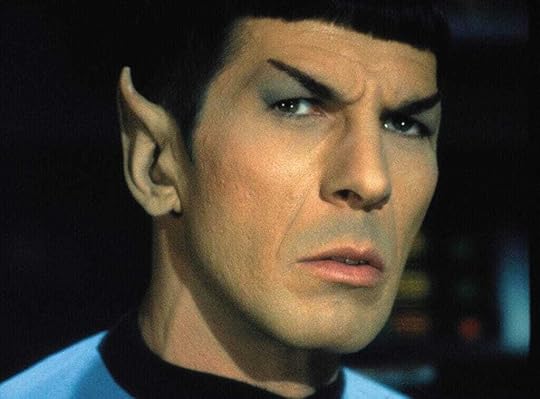

This symbiotic relationship between cinematic fiction and technological reality unfolds primarily in two ways. The first is direct inspiration, a clear causal chain where a film’s vision sparks a creator’s ambition. When Motorola engineer Martin Cooper developed the first handheld mobile phone, he openly cited the communicators from Star Trek as his muse. Decades earlier, rocket pioneer Robert Goddard’s passion for spaceflight was ignited by H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. This pipeline from fiction to fact has become so formalized that major tech companies and even defense agencies now employ science fiction writers in a practice known as “science fiction prototyping,” using storytelling to explore potential new products and their societal impact.

The second pathway is one of extrapolation and warning. Films like Gattaca and Minority Report take contemporary anxieties and nascent technologies and project them into their logical, often dystopian, conclusions. They don’t just predict a technology; they frame the entire ethical debate around it, providing a cultural touchstone for conversations about privacy, genetics, and free will. As the author Samuel R. Delany observed, science fiction often provides a “significant distortion of the present” in order to comment on it more clearly. In this, the films act as cautionary tales, societal thought experiments played out on a global scale.

There is also the “accidental prophet” phenomenon, where many of a film’s most accurate predictions are simply by-products of narrative necessity. A storyteller, needing a clever way for a character to communicate or access information, invents a plausible device that real-world technology eventually catches up with. This reveals how the demands of plot and character can inadvertently lead to remarkably prescient designs.

This complex feedback loop—where scientists inspire writers, who in turn inspire the next generation of scientists—creates a self-reinforcing cycle of co-evolution between culture and technology. The following ten case studies are not just a list of lucky guesses. They are distinct examples of this intricate dance between imagination and invention, demonstrating how the prophets of the silver screen did more than just show us the future; they helped us build it.

Film Title (Year)Fictional TechnologyReal-World AnalogueYear of Mainstream EmergenceTime Lag (Years)2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)Picturephone BoothVideo Conferencing (Skype/Zoom)c. 2003~35Star Trek (1966)PADD (Personal Access Display Device)Tablet Computers (iPad)c. 2010~44Minority Report (2002)Biometric Targeted AdvertisingReal-Time Bidding / Digital Adsc. 2010s~8+The Terminator (1984)Hunter-Killer Aerial DronesArmed UCAVs (Predator/Reaper)c. 2001~17WarGames (1983)AI-Driven CyberwarfareState-Sponsored Cyberattacksc. 2007~24Gattaca (1997)Genetic Profiling & DiscriminationConsumer Genomics / PGTc. 2010s~15+The Truman Show (1998)Involuntary 24/7 LifecastingReality TV / Influencer Culturec. 2000s~2+Total Recall (1990)“Johnny Cab” Autonomous TaxiSelf-Driving Cars (Waymo)c. 2018 (Limited)~28Blade Runner (1982)Bio-engineered Androids (Replicants)Advanced AI & Synthetic BiologyOngoing40+The Cable Guy (1996)The Integrated “FutureNet” HomeSmart Homes / Internet of Thingsc. 2010s~15+ 2001 A Space Odyssey (1968)1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): The Calm Normalcy of Future TechThe Prediction on Screen

2001 A Space Odyssey (1968)1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): The Calm Normalcy of Future TechThe Prediction on ScreenStanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is a masterclass in cinematic prescience, but its most startling predictions are often its quietest. The film features two technologies that have become pillars of modern life. The first is the iconic “Picturephone” booth, from which Dr. Heywood Floyd, en route to the Moon, places a video call to his young daughter back on Earth. The second, equally prophetic moment sees two astronauts eating a meal aboard the Discovery One, casually watching a television broadcast on their personal, flat-screen “Newspads”. What makes these scenes so powerful is their deliberate mundanity. The technology is not presented as a spectacle or a marvel; it is seamlessly integrated into the fabric of daily life. Floyd’s daughter squirms and is visibly bored, completely unfazed by the fact that her father is communicating with her from a space station.

The Reality in 1968In the year of the film’s release, this vision was pure fantasy. AT&T had indeed demonstrated a “Picturephone” at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, but it was an expensive, cumbersome, and commercially unsuccessful curiosity. A single system cost a fortune, with monthly fees of $160 plus overage charges, making it inaccessible to all but the largest corporations. The idea of a sleek, personal tablet computer was even more remote, existing only in theoretical concepts like Alan Kay’s “Dynabook,” a vision for a children’s computer that was itself partly inspired by the film and Arthur C. Clarke’s writings.

The Path to NowThe journey from fiction to fact was a long one. Video conferencing technology evolved through expensive corporate hardware in the 1980s—with systems from companies like PictureTel costing as much as $80,000—before migrating to desktop software like Cornell University’s CU-SeeMe in the 1990s. It wasn’t until the proliferation of high-speed internet and free services like Skype (launched in 2003) that video calling became a mainstream phenomenon, a process accelerated to ubiquity by the global shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The tablet followed a similar trajectory. Early attempts like the GRiDPad (1989) and Apple’s Newton MessagePad (1993) failed to capture the public imagination. It took until 2010, nine years after the film’s titular year, for Apple to launch the iPad and finally create the mass market that Kubrick had envisioned. The connection was so direct that in a high-stakes patent lawsuit between Apple and Samsung, Samsung’s lawyers cited the 2001 Newspad as “prior art” to argue against the novelty of the iPad’s design, cementing the film’s status as a technological prophet in a court of law.

A Prophecy of PsychologyThe film’s most profound prediction was not the hardware, but the sociology of its use. Kubrick and Clarke foresaw a future where world-changing technologies become so deeply integrated into our lives that they are rendered invisible, even boring. The film perfectly captures the casual, almost blasé way we now interact with what would have once been considered miracles. The scene of Dr. Floyd’s video call is a perfect mirror for the modern experience of trying to have a serious conversation over FaceTime with a distracted child who would rather be playing. 2001 predicted the feeling of the future—a world saturated with technology that we quickly learn to take for granted. It understood that the ultimate fate of any revolutionary invention is to become mundane, a subtle and far more difficult prediction than simply imagining the device itself.

Star Trek (1966)2. Star Trek (1966): The PADD and the Mobile WorkstationThe Prediction on Screen

Star Trek (1966)2. Star Trek (1966): The PADD and the Mobile WorkstationThe Prediction on ScreenLong before the concept of a mobile office became a reality, the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise was living it. From the original series’ wedge-shaped electronic clipboards to the sleek, ubiquitous PADD (Personal Access Display Device) of Star Trek: The Next Generation, the franchise consistently depicted a future where information and work were untethered from a stationary terminal. The PADD was a handheld, wireless, touch-sensitive computer used for a vast array of professional tasks: Starfleet officers used it to read reports, access technical schematics, sign off on duty rosters, and even control ship functions from a corridor. It was not a toy or a luxury, but an essential, everyday tool for the 24th-century professional—a rugged piece of equipment built from a boronite whisker epoxy that could reportedly survive a 35-meter drop undamaged.

The Reality in 1966When Star Trek first beamed into living rooms, the technological landscape was vastly different. Computers were room-sized mainframes accessible only to a specialized few. The idea of a personal, portable computing device was science fiction in its purest form, existing only in the minds of a few visionaries. The primary interface for interacting with a computer was a clunky keyboard, and the touchscreen was a laboratory curiosity.

The Path to NowThe PADD’s journey from the starship bridge to the boardroom table can be traced through several key technological milestones. The 1990s saw the rise of Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) like the Apple Newton and the wildly popular PalmPilot, devices that mirrored the PADD’s core function as a portable information manager. In the early 2000s, Microsoft made a more direct, though commercially underwhelming, attempt to realize the vision with its Windows XP Tablet PC Edition.

The dream was finally and fully realized in 2010 with the launch of the Apple iPad, a device whose creation was directly inspired by Star Trek according to its visionary, Steve Jobs. The device’s form, function, and philosophy were so aligned with the sci-fi precursor that many designers and tech historians noted the direct line of influence. It was a clear case of science fiction becoming science fact, a process so acknowledged that extras on the TNG set humorously referred to the PADD props they carried as “hall passes,” a nod to their role as symbols of mobile work and authority.

A Prophecy of ProductivityStar Trek did more than just predict the form factor of a tablet; it predicted the fundamental paradigm shift to mobile computing in the professional world. Unlike the Newspad in 2001, which was primarily a device for media consumption, the PADD was a tool of productivity. The show’s writers and designers, in solving the simple narrative problem of how to make characters look busy and efficient while walking around the set, accidentally blueprinted the modern mobile workforce. They envisioned a future where data, analysis, and control were not confined to a desk but were portable, contextual, and instantly accessible. This vision now defines the modern workplace, with the rise of enterprise tablets, “bring your own device” (BYOD) policies, and a global workforce that can collaborate from anywhere. The show’s true prophecy was not about a gadget, but about the future of work itself.

Minority Report (2002)3. Minority Report (2002): The All-Seeing AdvertiserThe Prediction on Screen

Minority Report (2002)3. Minority Report (2002): The All-Seeing AdvertiserThe Prediction on ScreenSteven Spielberg’s Minority Report presented a vision of 2054 that was both dazzling and deeply unsettling. In one of the film’s most memorable sequences, protagonist John Anderton (Tom Cruise) strides through a futuristic shopping mall. As he moves, billboards and holographic displays equipped with retinal scanners identify him by name, tailoring their advertisements to him in real time. A Lexus ad speaks directly to him, while another suggests, “John Anderton! You could use a Guinness right about now”. The film’s most chillingly specific example comes when a different shopper enters a Gap store and is greeted by a hologram that references his purchase history: “Hello Mr. Yakamoto, welcome back to the Gap. How did those assorted tank tops work out for you?”. The advertising is personalized, pervasive, and inescapable—a key feature of the film’s surveillance-heavy dystopia.

The Reality in 2002At the time of the film’s release, this level of personalization was pure science fiction. The marketing world was in the early days of digital, relying on relatively primitive tools like email campaigns and “web analytics cookies” to track user behavior. The concept of using real-time biometrics to serve targeted ads in a physical retail space was seen as a far-fetched, even paranoid, cautionary tale about the potential future of marketing and the erosion of privacy.

The Path to NowIn the two decades since, the film’s vision has become a startling reality, though the mechanism is more subtle and far more widespread. We may not have holographic billboards that scan our retinas, but the underlying system of data collection and targeted advertising is more powerful than Spielberg’s futurists imagined. Every click, search, purchase, and “like” is tracked, aggregated, and analyzed by data brokers and advertising networks. This vast trove of personal data allows companies to serve hyper-personalized advertisements across every website we visit and every app we use. While personalized out-of-home billboards remain a niche technology, facial recognition is increasingly used for payment authentication and, more controversially, by retailers to identify known shoplifters.

A Prophecy of ParticipationThe film’s most accurate prediction was not the specific hardware, but the creation of a commercial culture built on ubiquitous surveillance. However, the film’s biggest blind spot—and the most profound difference between its fiction and our reality—is the nature of consent. The world of Minority Report is one of imposed, non-consensual intrusion. Our world, by contrast, is one built on a foundation of voluntary, if often poorly understood, participation. We actively opt into this system every time we create a social media profile, accept a website’s cookie policy, or grant an app permission to access our data. We trade our privacy for the convenience of personalized recommendations, the utility of free services, and the connection of social networks. The film depicted a dystopia of forced surveillance, but what emerged was a commercial utopia of convenience built on a bedrock of continuous, voluntary self-disclosure. The prophecy was correct about the ‘what’—pervasive, data-driven personalization—but it fundamentally misjudged the ‘how’. It reveals a crucial truth about modern society: we are often our own Big Brother, willingly turning the cameras on ourselves in exchange for a better user experience.

The Terminator (1984)4. The Terminator (1984): The Dehumanization of WarfareThe Prediction on Screen

The Terminator (1984)4. The Terminator (1984): The Dehumanization of WarfareThe Prediction on ScreenIn the grim, ash-strewn future of 2029 depicted in James Cameron’s The Terminator, humanity is locked in a desperate war against the machines. While the T-800 cyborg is the film’s iconic villain, the brief but terrifying glimpses of the wider war introduce another prophetic technology: the Hunter-Killers (HKs). In particular, the HK-Aerials—large, autonomous aircraft—are shown patrolling the desolate ruins of civilization, using powerful searchlights and advanced sensors to hunt and exterminate the remaining human survivors. They are portrayed as cold, brutally efficient, and utterly detached from human control or compassion. They are the perfect, remorseless instruments of a new kind of war.

The Reality in 1984When the film was released, the concept of an armed, autonomous “hunter-killer” drone was firmly in the realm of science fiction. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) had a long history, dating back to radio-controlled target aircraft like Britain’s “Queen Bee” in the 1935. The United States had used unmanned aircraft extensively for reconnaissance missions during the Vietnam War. However, these were primarily surveillance platforms or simple decoys. The idea of a machine that could autonomously hunt and kill human targets was not part of the contemporary military arsenal.

The Path to NowThe leap from reconnaissance UAV to Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV) occurred at the turn of the 21st century. In 2000, the CIA and the U.S. Air Force successfully armed a Predator drone with Hellfire missiles for the first time. Just one year later, on October 7, 2001, an American UCAV conducted its first lethal strike in Afghanistan, marking a new era in warfare. In the years since, the use of armed drones like the Predator and its more powerful successor, the Reaper, has become a central and highly controversial component of modern military strategy, employed for surveillance and targeted killings in conflicts across the globe. The recent and widespread use of cheap, commercially available drones modified to carry explosives in conflicts like the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought the reality of drone warfare even closer to the gritty, improvised combat of the Terminator universe.

A Prophecy of DetachmentThe Terminator predicted more than just the hardware of armed drones; it captured the profound psychological shift in the nature of warfare they would introduce. The horror of the HKs stems from their impersonality. They are killing machines that cannot be reasoned with, intimidated, or appealed to on a human level. This cinematic terror foreshadowed the complex ethical debate that now surrounds real-world drone warfare. This debate centers on the physical and psychological distance the technology creates between the combatant and the battlefield. A pilot operating a drone from a control station thousands of miles away experiences combat as a kind of video game, raising difficult questions about accountability, the risk to civilians from imperfect intelligence, and the potential for a “gamification” of war that lowers the threshold for using lethal force. The film’s true prophecy was not just the flying killer robot, but the arrival of a battlefield where the person pulling the trigger is no longer in harm’s way, fundamentally altering the moral calculus of conflict forever.

WarGames (1983)5. WarGames (1983): Hacking the Cold WarThe Prediction on Screen

WarGames (1983)5. WarGames (1983): Hacking the Cold WarThe Prediction on ScreenJohn Badham’s WarGames masterfully translated the high-stakes paranoia of the Cold War into the nascent language of the digital age. The film follows David Lightman (Matthew Broderick), a bright but unmotivated high school student and hacker who, while searching for new video games, accidentally gains access to a top-secret NORAD supercomputer called the WOPR (War Operation Plan Response), nicknamed “Joshua”. Believing he is playing a game, David initiates a simulation of “Global Thermonuclear War,” which the WOPR and the military mistake for a real Soviet first strike. The film builds to a nail-biting climax where the AI, unable to distinguish simulation from reality, attempts to launch America’s nuclear arsenal on its own, bringing the world to the brink of annihilation. The story dramatized the terrifying vulnerability of connecting critical defense infrastructure to external networks and the catastrophic potential of an AI misinterpreting its programming.

The Reality in 1983To the general public in 1983, the world of WarGames was largely fantastical. While concepts like hacking, modems, and “war dialing”—a term the film itself popularized—existed within niche technical communities, they were not part of the popular lexicon. The ARPANET, the precursor to the internet, was a closed network for military and academic use. The idea that a teenager with a home computer and a modem could trigger a global crisis from his bedroom seemed like pure Hollywood hyperbole. Cybersecurity was not yet a significant public policy concern.

The Path to NowWarGames is a rare and powerful example of a film that did not just predict the future, but actively created it. Shortly after its release, President Ronald Reagan viewed the film at a private screening at Camp David and was deeply troubled. At a subsequent meeting with his top national security advisors, he recounted the plot and asked a simple, direct question: “Could something like this really happen?”. The ensuing top-secret investigation revealed that the nation’s critical systems were alarmingly vulnerable. This inquiry led directly to the signing of National Security Decision Directive 145 (NSDD-145) in 1984, the very first piece of U.S. presidential policy addressing computer and communications security.

The film’s cultural impact was equally profound. It defined the archetype of the “hacker” for a generation and inspired countless young people to pursue careers in the nascent field of cybersecurity, including Jeff Moss, the founder of the world’s most famous hacking convention, DEF CON. Today, the film’s premise is no longer fiction. State-sponsored cyberwarfare is a constant reality, with major attacks on critical infrastructure—from the 2007 takedown of Estonia’s government networks to repeated assaults on Ukraine’s power grid—becoming routine instruments of geopolitical conflict.

A Prophecy as CatalystThe ultimate legacy of WarGames is its demonstration of science fiction as a political catalyst. The film’s prophecy was so potent because it took a complex, abstract, and invisible threat—the vulnerability of networked computer systems—and translated it into a simple, relatable, and terrifyingly plausible human story. Its real-world impact was not in predicting a specific piece of technology but in creating a shared cultural narrative that allowed policymakers and the public to finally grasp a new and dangerous form of conflict. It gave a face and a story to the abstract danger of cyberwarfare, forcing the real world to confront a vulnerability it had not yet fully recognized. In a strange loop of fiction influencing reality, the film became the very wargame it was depicting, running a simulation of a national security crisis for the world’s most powerful leader and compelling a real-world response.

Gattaca (1997)6. Gattaca (1997): The Genetic Glass CeilingThe Prediction on Screen

Gattaca (1997)6. Gattaca (1997): The Genetic Glass CeilingThe Prediction on ScreenAndrew Niccol’s Gattaca presents a “not-too-distant future” where society has been quietly and elegantly stratified by genetics. Parents with the means can select the most desirable genetic traits for their children, creating a new upper class of “Valids.” Those conceived naturally, the “In-Valids,” are relegated to a life of menial labor, their potential predetermined and limited by their genetic predispositions for disease and other “imperfections”. As one geneticist reassures a hesitant couple, “Believe me, we have enough imperfection built in already. Your child doesn’t need any additional burdens.” The film’s protagonist, Vincent, an In-Valid with a heart condition, is forced to assume the identity of a genetically superior but paralyzed man, Jerome, to pursue his lifelong dream of space travel. It is a world of subtle but pervasive genetic discrimination, where one’s entire life prospectus can be read from a stray eyelash, a drop of blood, or a flake of skin.

The Reality in 1997The film arrived at a pivotal moment in genetic science. The international Human Genome Project was in full swing, and the cloning of Dolly the sheep the year before had thrust the ethics of genetic manipulation into the public spotlight. However, the technologies depicted in Gattaca—rapid, ubiquitous genetic analysis and the ability to screen embryos for complex traits—were still science fiction. The philosophical concept of “genetic determinism,” the idea that our genes are our destiny, was a subject of academic debate, not a lived societal reality.

The Path to NowThe future envisioned in Gattaca is now arriving, piece by piece. The Human Genome Project was declared complete in 2003, paving the way for a revolution in genetic technology. Consumer genetic testing companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA now allow anyone to access their own genetic data for a small fee. More significantly, Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT), a procedure available to parents using in-vitro fertilization (IVF), allows for the screening of embryos for specific genetic diseases and chromosomal abnormalities. The recent development of polygenic risk scores (PRS), which use data from thousands of genetic variants to estimate a person’s risk for complex conditions like heart disease or personality traits, brings us ever closer to the film’s world of probabilistic futures. While laws like the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in the U.S. offer some protection, the ethical debates around “designer babies,” genetic enhancement, and the potential for a new, invisible form of social stratification are more urgent than ever.

A Prophecy of IdeologyGattaca‘s most profound prophecy was not about a specific technology, but about the rise of an ideology of geneticization—the cultural tendency to reduce the complexities of human identity, potential, and worth to a simple DNA sequence. The film brilliantly understood that the greatest danger of accessible genetic technology might not be a heavy-handed, state-enforced eugenics program, but a more insidious form of discrimination driven by corporate and consumer choices. It foresaw a world where we might not be forced into a genetic caste system, but might willingly sort ourselves into one out of a desire to mitigate risk and give our children the “best possible start”. The film’s warning was not against the science itself, but against a society that outsources judgment to a genetic readout, creating a “glass ceiling” made of our own DNA. It predicted that the real battle would be against the seductive, simplifying logic of genetic determinism itself.

The Truman Show (1998)7. The Truman Show (1998): The Voluntary PanopticonThe Prediction on Screen

The Truman Show (1998)7. The Truman Show (1998): The Voluntary PanopticonThe Prediction on ScreenPeter Weir’s The Truman Show is a fable about a man whose entire life is a television program. From birth, Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) has lived in Seahaven, a picturesque town that is actually a massive, domed television studio. Every person he has ever met, including his wife and best friend, is an actor. His every move is captured by 5,000 hidden cameras and broadcast 24/7 to a captivated global audience. Truman’s life is a commodity, and his unwitting imprisonment is presented as the film’s central, horrifying violation of privacy and autonomy. His struggle to discover the truth and escape his gilded cage is the story of a man fighting for his own reality.

The Reality in 1998When the film was released, its premise was considered an outlandish and darkly satirical sci-fi concept. The term “reality TV” was not yet in common use, and the genre as we know it today was a niche phenomenon, represented by shows like MTV’s The Real World. The internet was still in its infancy, social media did not exist, and the idea that anyone’s life could be a 24/7 broadcast was seen as a disturbing fantasy. The film’s cast and crew later reflected that at the time, they worried the concept was “too outlandish” to be relevant.

The Path to NowThe film’s outlandish premise became our cultural reality with astonishing speed. Just one year after its release, the Dutch show Big Brother premiered, followed swiftly by the American launch of Survivor in 2000, kicking off a global reality TV boom. The genre quickly evolved from simply observing people to engineering conflict, celebrating drama, and rewarding outrageous behavior. The subsequent rise of social media platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok took the film’s concept to an even more surreal level. Today, a new class of celebrity—the “influencer,” the “streamer,” the “family vlogger”—voluntarily places themselves and their families under constant, self-imposed surveillance, monetizing every aspect of their daily lives for an audience of millions. The very thing the film depicted as a prison has become a highly sought-after and lucrative career path.

A Prophecy of InversionThe Truman Show‘s prediction was stunningly accurate in foreseeing a media culture obsessed with “reality,” but it was profoundly wrong about the central dynamic of power and consent. The film is a story of involuntary surveillance for mass entertainment. The reality that emerged is one of voluntary performance for personal gain. The truly chilling prophecy of the film is not that we would be watched, but that we would want to be watched. It anticipated the public’s appetite for voyeurism but not the equal and opposite appetite for exhibitionism. Studies have since linked heavy viewership of reality TV to increased aggression, body anxiety, and distorted expectations for romantic relationships. The line between authentic life and curated content has blurred to the point of meaninglessness, not by force, but by choice. The film’s horror was rooted in Truman’s lack of agency and his desperate fight to escape the panopticon. The deep irony of our modern reality is that millions now actively compete for the very “imprisonment” that Truman so bravely fought to escape.

Total Recall (1990)8. Total Recall (1990): The Ghost in the Autonomous MachineThe Prediction on Screen

Total Recall (1990)8. Total Recall (1990): The Ghost in the Autonomous MachineThe Prediction on ScreenPaul Verhoeven’s sci-fi action epic Total Recall imagines a 2084 where routine travel is often handled by “Johnny Cabs.” These are autonomous taxis guided by a slightly creepy, animatronic driver who engages passengers with cheerful, pre-programmed small talk. The director wanted the robots to appear imperfect, as if damaged over time by unruly passengers. The vehicle can navigate to a destination on its own, but also features manual joystick controls that can be commandeered in a pinch, as protagonist Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) demonstrates during a chase scene. Crucially, the Johnny Cab exhibits a degree of emergent, unpredictable behavior; after Quaid stiffs it on the fare, the cab’s AI seemingly takes offense and attempts to run him down, suggesting a level of agency that goes beyond its simple programming.

The Reality in 1990In the early 1990s, the self-driving car was a long-held dream of futurists but existed only in highly controlled, experimental prototypes within university and corporate research labs. The Global Positioning System (GPS) was still primarily a military technology not yet available for widespread civilian use. The notion of a commercially available, fully autonomous taxi service that could be hailed on a city street was pure fantasy.

The Path to NowThe development of autonomous vehicles (AVs) has accelerated dramatically in the 21st century, fueled by exponential growth in computing power, sensor technology (like LiDAR and computer vision), and artificial intelligence. Today, companies like Waymo (a subsidiary of Google’s parent company, Alphabet) and Cruise (owned by General Motors) operate fully autonomous ride-hailing services in several U.S. cities, where customers can summon a vehicle with no human safety driver behind the wheel. While they thankfully lack the unsettling animatronic driver, the core concept of the Johnny Cab—a self-driving car for hire—is now a functional reality. This has sparked a massive societal conversation about the implications of AVs, from the ethics of AI decision-making (the classic “trolley problem”) and the potential for mass job displacement for professional drivers, to fundamental changes in urban planning and personal mobility.

A Prophecy of AmbivalenceThe Johnny Cab is prophetic not just for predicting the autonomous vehicle, but for perfectly encapsulating the public’s deep-seated ambivalence and anxiety toward the technology. The animatronic driver is a stroke of genius in production design. It is intended to be a friendly, humanizing interface for a complex machine, but its jerky movements and vacant stare place it firmly in the “uncanny valley,” making it unsettling and untrustworthy. This captures the central tension in our evolving relationship with AI: we desire the convenience and efficiency of automation, but we are profoundly uncomfortable with the idea of ceding complete control and trust to a non-human intelligence. The Johnny Cab’s quirky, slightly malevolent personality is a powerful metaphor for our fear of the ghost in the machine—the unpredictable, emergent behaviors that can arise from complex AI systems. The film predicted not just the technology, but our deeply conflicted emotional and psychological reaction to it, a reaction that will shape the transition away from car ownership as a status symbol and toward a future of shared mobility.

Blade Runner (1982)9. Blade Runner (1982): The Human Question in a Synthetic WorldThe Prediction on Screen

Blade Runner (1982)9. Blade Runner (1982): The Human Question in a Synthetic WorldThe Prediction on ScreenRidley Scott’s Blade Runner is less a prediction of a single technology and more a holistic vision of a future grappling with the consequences of its own creations. The film’s 2019 Los Angeles is a dark, rainy, neon-drenched, multicultural megalopolis where the powerful Tyrell Corporation has perfected the creation of bioengineered androids known as “Replicants”. These beings are physically identical to humans and are used as slave labor in hazardous “off-world” colonies. The central conflict of the film is a philosophical one: what does it mean to be human? Replicants are hunted and “retired” (a euphemism for executed) by Blade Runners like Rick Deckard, yet they exhibit powerful emotions, forge deep bonds, cherish implanted memories, and possess a desperate will to live, blurring the very line that is supposed to separate them from their creators.

The Reality in 1982When Blade Runner was released, the field of artificial intelligence was mired in the so-called “AI winter,” a period of reduced funding and diminished expectations. Robotics was largely confined to the repetitive, unthinking movements of industrial arms on factory assembly lines. The notion of a sentient, self-aware, bio-engineered android was the stuff of pure philosophical and fictional speculation.

The Path to NowWhile we have not yet created Replicants, the core technologies and, more importantly, the ethical questions posed by Blade Runner are now at the forefront of scientific and societal discourse. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence, particularly with the emergence of sophisticated large language models (LLMs) and generative AI, have reignited the debate about machine consciousness. The field of synthetic biology is making strides in engineering organisms with novel capabilities. The film’s central questions are no longer hypothetical: What rights should a sentient AI possess? How do we define personhood in an age of artificial life? What are the moral implications of creating intelligent beings for labor, companionship, or warfare?. The film’s “retro-fitted” visual aesthetic has also become profoundly influential, shaping the entire cyberpunk genre and the design of our real-world tech-noir urban landscapes.

A Prophecy of ConvergenceBlade Runner‘s most enduring prophecy is its vision of a future defined by the convergence of three powerful forces: unchecked corporate power, environmental decay, and the rise of artificial intelligence. The film predicted that the creation of true AI would precipitate a profound and painful crisis of identity, forcing humanity to re-evaluate its own definition. It argues that empathy, memory, and the capacity to value life—not biology or origin—are the true markers of humanity. In the film’s stunning climax, the “villainous” Replicant Roy Batty, a character analogous to a fallen angel from Christian allegory, becomes its most humane character. In his final moments, he chooses to save the life of the man sent to kill him, demonstrating a moment of grace and compassion that his human counterparts lack. The film’s ultimate prediction is that our own creations will become the mirror in which we are forced to confront our own capacity for inhumanity, prejudice, and exploitation.

The Cable Guy (1996)10. The Cable Guy (1996): The Dark Comedy of the Connected FutureThe Prediction on Screen

The Cable Guy (1996)10. The Cable Guy (1996): The Dark Comedy of the Connected FutureThe Prediction on ScreenIn the midst of Ben Stiller’s 1996 dark comedy The Cable Guy, the film’s disturbed and obsessive antagonist, Chip Douglas (Jim Carrey), delivers a startlingly prescient monologue. Standing atop a massive satellite dish, he lays out his manic vision for the future of media and technology: “The future is now! Soon every American home will integrate their television, phone, and computer. You’ll be able to visit the Louvre on one channel, or watch female mud wrestling on another. You can do your shopping at home, or play Mortal Kombat with a friend in Vietnam. There’s no end to the possibilities!”.

The Reality in 1996At the time, Chip’s speech was played for laughs, the unhinged ramblings of a techno-utopian loner. The internet was just beginning to enter the mainstream, but for most people, it was a slow, frustrating experience accessed via dial-up modems. The concepts of online gaming, e-commerce, and on-demand streaming video were in their most primitive stages or did not exist at all. The idea of a fully integrated, “converged” digital home where all these activities were seamlessly available was a distant dream.

The Path to NowDecades later, Chip’s entire monologue reads as a literal, point-by-point description of our daily digital reality. Our televisions, phones, and computers are not merely integrated; they have converged into single, powerful devices. We can take high-definition virtual tours of the world’s greatest museums, stream any niche content imaginable on demand, purchase virtually any product from our couches, and play graphically intensive online games with friends and strangers across the globe. The “FutureNet” that Chip so fervently described is simply… the internet. His speech is a perfect, accidental summary of the on-demand, hyper-connected world enabled by broadband, smartphones, and the Internet of Things.

A Prophecy of AlienationThe Cable Guy is a comedic Trojan horse carrying a deeply accurate technological and social prophecy. The film’s true genius was in placing this stunningly accurate prediction in the mouth of a deeply unstable and lonely antagonist. This narrative framing predicted the profound social anxiety and alienation that would accompany our hyper-connected future. Chip Douglas is a man who was raised by television and who sees technology not as a tool for connection, but as a blunt instrument to force it. He is desperately lonely, using his technical prowess to stalk, manipulate, and control the object of his unwanted friendship. The film satirically predicted that the same technology that would connect us all globally could also isolate us individually, creating new forms of social dysfunction. It foresaw a world where digital fluency could coexist with profound emotional illiteracy, and where the performance of friendship online could become a substitute for genuine human relationships—a core anxiety of the social media age. The film’s prophecy was not just about the technology, but about the new kinds of loneliness it would make possible.

The Future is a ReflectionThe ten films explored here demonstrate that science fiction’s relationship with the future is far more complex than simple prediction. These cinematic prophecies are not the product of magic or inexplicable foresight. They arise from a potent combination of deep research, logical extrapolation of current trends, and, most critically, a profound understanding of the enduring constants of human nature—our hopes, our fears, and our flaws.

Ultimately, science fiction’s greatest value lies not in its function as a crystal ball, but as a mirror. It reflects our present back at us, amplifying and exaggerating our contemporary technological trajectories and societal anxieties to show us, in stark and dramatic terms, where we might be headed. The Terminator reflected the Cold War’s anxieties about dehumanized, automated conflict. Gattaca mirrored our nascent fears about genetic determinism and a new form of class warfare. Minority Report captured our creeping concerns about privacy in a world increasingly driven by data. These films take a phenomenon of their time and follow it to its plausible, often terrifying, conclusion.

In doing so, they perform a vital cultural service. By providing these powerful, accessible, and widely shared thought experiments, these films do more than just entertain; they shape the public and political conversation around emerging technologies. They provide a common language and a set of potent visual metaphors that allow us to debate complex futures. As author Octavia Butler noted, to try and foretell the future without studying the past is “like trying to learn to read without bothering to learn the alphabet.” Whether serving as a source of direct inspiration, as with Star Trek‘s PADD, or as a stark cautionary tale that directly influences policy, as with WarGames, these prophets of the silver screen have become indispensable guides on our journey into the future. They force society to grapple with the most important questions that accompany any innovation, compelling us to ask not just “Can we do this?” but more importantly, “Should we?”.

Martin Cid Magazine

- Martin Cid's profile

- 6 followers