Making of a Poem: Eugene Ostashevsky on “Falling Sonnet XI”

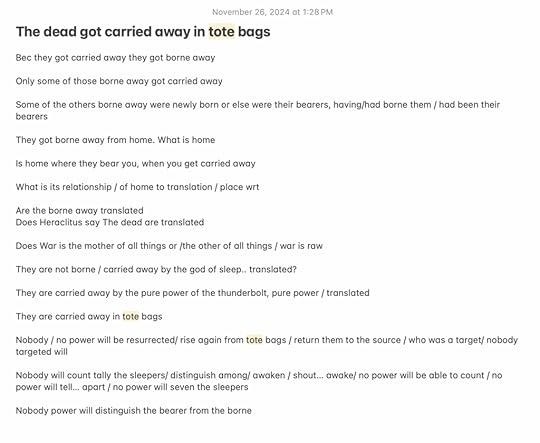

The second draft of “Falling Sonnet XI.”

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets and translators to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Eugene Ostashevsky’s “Falling Sonnet XI” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 252.

How did you come up with the title for this poem?

This is the eleventh poem in a series called Falling Sonnets. They are “sonnets” in the sense that each has fourteen lines with a Petrarchan logical structure, although without meter or rhyme. Right now, there are twelve, although I would prefer to have fourteen. The series reacts to one of the wars currently being fought. I’d prefer not to name which one—as soon as you do, the poem’s reception depends on how readers feel about the war rather than on anything having to do with the poem. Four other poems from the series have recently appeared in n+1.

My most recent book is called The Feeling Sonnets, and sections in it are called “Fooling Sonnets,” “Feeding Sonnets,” and even “Leafing Sonnets.” When I finished, I wanted to stop writing these sonnets, which aren’t real sonnets, anyway. But I was too busy to lay aside enough time to develop a new form for a new book, so I kept writing them, much to my chagrin. This is why I call my new sonnet book “The Failing Sonnets,” and a part of it is a cycle called “The Falling Sonnets,” because it reacts to a war that feels as if it had my name on it and that destabilizes my sense of self in unpleasant ways.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

I usually generate ideas by playing with words. The first draft (below) shows me coming up with the first terms of “Falling Sonnet XI” while writing another poem. In this poem, the main term was alien. Although I was thinking of it in the sense of “a person from elsewhere,” I also split alien up into a lien and looked up the financial sense of the word alienation, which yielded “disposal of property.” Disposal of property gave the association of “tote bag,” and then the disposal of bodies, because tot in German is “dead.” This link became the seed of a new poem. (The final draft of the “alien” poem was published here.)

The second draft (see image at top of post) shows me working on “Falling Sonnet XI.” Tote gave me carry and carried away, with its two meanings, the physical and the emotional, and then borne / born, bear away / bear with, bear a child / pallbearer, and the like. Translate enters the same line of synonyms of carry because it means “to bear across.” Translation may refer to reburial of remains, especially royal remains, like when the bodies of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were translated to Saint-Denis in 1815. I also think of translate as transform, such as Bottom’s acquiring an ass’s head in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As another character comments, “Bottom, thou art translated.”

In this way, “Falling Sonnet XI” became a poem about the reburial of body parts pulled out from the remains of buildings that were collapsed by bombing or missile strikes.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

The second draft shows explicit literary associations that got ironed out of the final version, although the thoughts they enabled remained. There appears the name of Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher who argued that things change into their opposites. I was thinking of fragment 27 in Guy Davenport’s great translation—“In death men will come upon things they do not expect, things utterly unknown to the living.” The second draft also recalls fragment 53, which declares war the king of all, and another fragment, which says the same of lightning. But I was equally remembering the theophany of Zeus and Semele. He shows himself to her in his real state, as lightning, and it kills her. The final version of my poem has the opposition between sleep and death as that between oral interpreting and written translating. I remember that I was thinking of the Euphronios Krater that used to be at the Met, on which Hermes directs Sleep and Death to carry Sarpedon away. And the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, because they appear in the eighteenth sura of the Quran, which I was teaching that month.

These associations for me are shorthand, and I try to get rid of them as I work on the text. Literary associations are often not art but the products of erudition. They are an imperfection inasmuch as they are too forbidding to many readers. Unfortunately, my poetry retains many literary associations, and these can be crucial to understanding the poem, but I am not happy about it and would prefer merely to connect words. For me, art lies in verbal connections. These can consist of using the same word with different meanings or else rethinking its meaning through true etymology or else bringing the word into contact with words that resemble it formally, in sound or shape. For me, poetry is thinking in words, by which I mean following the different meanings that come together in the same word or in similar word forms.

On second thought, I am not against all literary associations. They can create great emotional depth through a kind of secret language. Some of the most moving moments in literature are intertextual, like when Dante, upon seeing Beatrice in Purgatorio, speaks the words about love and remembrance that Virgil gives Dido. And it is then that Virgil, unobserved, returns to Limbo … That scene is not merely erudition but great art, and it is heartrending. But only when the reader understands not just the similarity but also the difference in the allusion, and the semantic work that the allusion performs, which is almost always that of irony, because irony is when you expect coincidence and get divergence instead. Still, the text should not depend on the allusion. It should make sense even to those who do not notice the allusion, which simply provides it with a double bottom. The problem does not lie with making the allusion but rather with wearing it on your sleeve, as an armband that says, “O reader, attend to the allusion here!” This is why I try to get rid of literary associations in the final drafts, but I often fail.

Eugene Ostashevsky is the author of, most recently, The Feeling Sonnets.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers