What is Excellence?

Okay, so I’ve been reading Human Accomplishments by Charles Murray.

In this book, as part of, basically, an extremely extended introduction, Murray presents a defense of the concept of excellence and of the basic human ability to identify excellence. This is interesting and persuasive, and I’m going to summarize it here to help myself understand it, and you can see what you think.

The assertion: Excellence is a thing.

Excellence is a thing, humans evolved in such a way as to find certain qualities attractive and worthy, and Michelangelo’s David is objectively a work of timeless excellence, while the dinosaur your five-year-old made out of clay in kindergarten isn’t. This is my example, not Murray’s.

I think this is obviously true. Moving on to the sub-assertions.

Sub-assertion one: It’s difficult to be so good at something that you create a work of enduring genius.

“Enduring” means a lot of people still admire your work after 100 years. (My summary, remember.) This isn’t as obviously true, because how much of a role does luck play in whether a work endures? And the answer is: not as much as you’d think; the sheer difficulty of creating works of enduring genius is more important.

Whole chapter defending this sub-assertion; eg, alllll about the Lotka curve as it emerges in many fields of human endeavor. Have I mentioned that my first dog’s name was Lotka? Yes, after this Lotka, though not with this particular curve in mind. Yes, I got my first dog when I was in grad school; why do you ask?

My Lotka, 1994-2208. He had four obedience titles, which doesn’t reflect his sheer brilliance. Brain the size of a walnut, yet he was practically telepathic.

Moving on!

Sub-assertion two: Your emotional fondness for a thing has nothing to do with excellence.

Or at least, not a lot. You can be very fond of the singing fish your uncle gave you. Your emotional attachment to the singing fish is not a judgment of its intrinsic excellence as a work of art; it’s sentiment, which is not the same thing.

I think this is clearly and obviously true and needs no defense.

Sub-assertion three: Some people have a much better ability to judge excellence in a specific field of endeavor than others because their experience with and knowledge of that field is much more extensive than average.

Sub-assertion four: The nature of a person’s appreciation of a thing depends on the level of their expertise with that thing.

I think these assertions are clearly and obviously true as well, and I will step way outside any field Murray discusses to lift an example from practical experience: Seeing the anatomical soundness of a dog or a horse – an animal that is standing right in front of you in full view – is a learned skill. Most pet owners do not see structure outside the most absolutely glaringly obvious facts, such as “that Dachshund is short.”

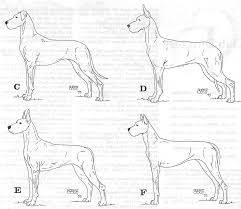

Check this out:

This drawing is from An Eye from a Dog by Robert Cole, by far my favorite resource for learning about canine structure, by the way. Cole is a judge, knowledgeable about both type and structure, and also capable of doing these great, clean line drawings, often based on real animals, that illustrate everything exactly as he wants to show it. I flipped to the Dane images because Great Danes have no coat to speak of and giant bones, so you can see everything about them very clearly.

Compare all four dogs. Is it obvious which ones are the best-constructed, soundest dogs, or do you only notice the ears? If you have more of a natural eye, you might think something vague, such as “Dog F is sort of spindly, isn’t she?” This would not exactly be wrong, but it would be … all right, it would be mostly wrong, though she is sort of spindly.

Anyone knowledgeable about functional structure can see at once that C and E are both good. I like C’s neck better, but E’s front better. But they are both fine.

D and F are both terrible, and of the two, it’s hard to choose which is worse. D has an ewe neck and overly long and sloped front pasterns — a serious fault in a big dog, inviting breakdown in the front. She has an abrupt angle where the withers should lead into the back, showing that her shoulder layback is not correct. She’s overangulated in the rear, she’s too long in the loin, her croup is steep. My vote for Most Likely To Suffer Back Issues is D.

F also has a sharp angle between neck and withers, caused by a direly upright shoulder — she lacks every kind of angulation in the front, her whole torso has been shoved upward on the stilts of her front legs, popping her chest up above her elbows. Her front pasterns, far too upright, are worse than the overly sloped pasterns seen in D. F is cruising toward orthopedic breakdown in the front. Her rear lacks angulation too, but not nearly as severely as her front. My vote for Most Likely To Suffer Orthopedic Breakdown is F. That front is dreadful.

No one who knows nothing about structure will be able to see any of this unless every feature of the dog is painstakingly pointed out. The judgment that B and E are structurally much more sound than the D or F s a judgment of objective quality. Nothing about it is subjective. The subjective part is stating that the sound dogs are more attractive. This is also true, because once you learn to see soundness, then correct anatomy is in fact more attractive than incorrect, unsound anatomy. The size, color, and fluffiness of the dog – almost the only physical features most pet owners see – recede in importance to the point that the expert barely notices those features.

“I don’t like natural ears much,” says the non-expert, looking at a ring filled with Great Danes. “Ears?” says the expert. “Oh, I guess I don’t either, now that you mention it, but her front is good, her shoulder’s nice, her topline is smooth — she’s far, far better put-together than those behind her.”

So, when someone says, “Experts can see things about paintings that nonexperts can’t see, or can see only when these features are painstakingly pointed out to them,” I have no trouble believing that’s true. Or a piece of music, or some other work of art. Or a sport. I know when I like a painting or a piece of music. I’m so perfectly ignorant about team sports that I can’t even express a preference. All events in football are essentially equally opaque to me. I know nothing about any of it and have zero ability to judge the relative greatness of football players.

Naturally, I have strong opinions about quality in writing.

And to the left, three yards beyond,

You see a little muddy pond

Of water – never dry

I measured it from side to side:

‘Twas four feet long, and three feet wide.

Compard to a quite different fragment, also by —

Was it for this

That one, the fairest of all rivers, loved

To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song,

And from his alder shades and rocky falls.

And from his fords and shallows, sent a voice

To intertwine my dreams?

The poem on the top is silly and pointless; and the poem below is excellent and that’s the way it is. Practically everyone is going to agree, and this is an important component of Murray’s argument that excellence is a thing:

Sub-assertion Five: Excellence is measurable because experts in a field routinely and predictably converge in their opinions.

What Murray is arguing here is that, by and large, the reason people who know a lot about a subject prefer A to B is because A is better than B – intrinsically better, objectively better. This remains true for experts regardless of nationality, by the way; eg, Western experts and Chinese experts converged in opinion about Chinese art. Art and music are easily perceived by anybody with vision and hearing, but to avoid bias when assessing opinions about literature, Murray excluded reference sources written in the language of the author; eg, the importance of English authors was assessed by looking only at the opinions of experts writing in languages other than English. That’s clever, and should pretty well do the job. There’s lots more about the statistical methods used in this book.

But here’s a sub-assertion that Murray doesn’t explicitly pull out as an assertion, though it is:

Sub-assertion Six: Excellent works invite extensive study, especially study by experts, in a way that works of lesser quality do not.

Another way of determining whether a work of art is excellent is by assessing this trait: whether the artwork invites and rewards prolonged study, especially prolonged study by people who know a great deal about the field. Here’s what Murray says about this:

The prolonged study of Bach’s music does not become boring. Bach’s music keeps presenting new facets to examine. … The person who knows a lot about art can look at Titian’s Venus of Urbino for a long time, and the looking alone – not the social context of Titian’s era, not the meaning of the female nude in the construction of gender, not what sort of person Titian was, but just the looking – absorbs the full attention of the expert.

The people who know the most about an artistic field are drawn to certain works. The qualities that draw their attention are those that offer the biggest payoff in the aesthetics of the art, and this payoff is based on qualities distinct from subjective sentiment.

and also

On topics about which we know a lot, we [all of us] have concrete reasons for concluding that amateur observations are either wrong or boringly obvious.

Bold is mine. That last is like me saying, “Oh, yeah, true, the dog has natural ears, but so what, look at her shoulder layback.” Pointing out that the dog has natural ears is not wrong, but it’s trivial.

Or again, like someone saying, “That dog looks strong!” and me saying, “No, he doesn’t look strong, he looks like an orthopedic disaster waiting to happen – he has loaded shoulders, he’s out at the elbow, his chest is tremendously too flat and wide, in what universe can this dog be said to look strong?” In this case, the non-expert is flatly wrong in his perception because he does not know anything about functional anatomy.

But back to excellence, this time excellence in literature.

This all makes me think of the time fairly recently on Quora where I stated flatly that Tolkien was a far, far better writer than Terry Brooks. And there’s a certain amount of “It’s all opinions anyway” and “Tolkien is a bad writer in my opinion” and so forth in the comments, and I am now thinking: The prolonged study of The Lord of the Rings does not get boring. The person who knows a lot about literature can contemplate The Lord of the Rings for a long time, and the work alone – not the social context of Tolkien’s era, not the meaning of fantasy settings and fairy tales in human history, not the roles of female characters in the story, not what sort of person Tolkien was, but just the work itself – absorbs the full attention of the expert.

I think: If I were going to be stuck on a desert island with one work of literature for the rest of my life, just one, this is a top contender for the one work I would pick. And I would be absolutely gobsmacked if anybody ever said the same about anything by Terry Brooks, and I think the difference is exactly what Murray is talking about here.

And I will just note that if you search for “nonfiction books about Tolkien,” there are dozens – I mean, I counted dozens and then got bored and stopped counting; there could be hundreds for all I know. If you look for nonfiction books about Terry Brooks or the Shannara series, there aren’t any. The next time I decide to start that argument, I’ll mention that, and this idea that TLotR does not get boring, as evidence that all opinions about quality may not be equal and that sentiment or enjoyment aren’t the same thing as excellence.

And of course it is worth mentioning here that expertise in a field is what allows someone to say, “I loathe this book and everything about it, here are the things I hate about it, but it is nevertheless an excellent book.” Or a piece of music, say, or I suppose any kind of artwork. I’m largely bored by portraits; I prefer landscapes. I don’t mistake that for anything but irrelevant personal preference. Separating preference from judgment is something someone distracted by sentiment can’t do, especially if this person does not have any depth of knowledge about the field. This is what leads to people saying, “The Sword of Shannara is just as good as The Lord of the Rings.” They don’t notice the craft or even the plot, and they mistake their liking of the book for a judgment of quality.

So, to sum up this summary:

What is excellence in literature? Is there such a thing as excellence, or is it all “I know what I like” and nothing is objective and The Sword of Shannara is just as good as The Lord of the Rings because it’s all about sentiment and there’s nothing real?

No one, unless bludgeoned into it by some instructor, actually thinks there’s no such thing as excellence. Anyone can see that yes, of course there is, and everyone can see this most readily in a field where they are experts.

While some nonexperts may prefer The Sword of Shannara, zero experts think that it is comparable in quality – though for reasons of sentiment, it’s possible some expert somewhere likes it better. (In theory, anyway.) And this is because TLotR is genuinely excellent and the Shannara books aren’t.

So, to reprise:

Excellence is a thing.

Sentiment is not a measure of excellence.

There is such a thing as breadth and depth of knowledge in a field. People who have this are experts in the field.

Experts in a field are generally much better able to judge excellence in that field than non-experts, and the things they assess are not the same as the things non-experts notice.

Excellence is at least somewhat measurable, because the opinions of experts broadly converge. This leads to lots of references to excellent things and nonfiction books about excellent things.

And, one more note from Murray’s book: evidently the single most frequently expressed opinion, by experts, about the very best works, is: How is it possible that a human person created this? Evidently people say this about Beethoven, about Michelangelo — and about the best Chinese poets — and about the very best in any field. How is this possible? It’s beyond comprehension anyone mortal could write like this / compose like this / paint like this / create this beautiful work.

The whole thing makes me want to listen to Beethoven’s 5th Symphony and gaze at Michelangelo’s David. And go look at the Sistine Chapel. I’ve been there, but now I want to go look at it again. The tour of the Vatican was the highlight of the one trip I’ve taken to Italy.

Painted gallery ceiling at the Vatican

Another painted ceiling

This one was in Venice, which come to think of it was another highlight.

People really do produce the most astounding art. We ought to start building amazing buildings again, and painting the ceilings.

Please Feel Free to Share:

The post What is Excellence? appeared first on Rachel Neumeier.