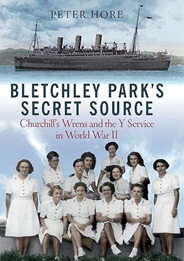

Review of Bletchley Park’s Secret Source, by Peter Hore, pub. Greenhill Books 2021

Now everybody's heard of Bletchley Park and the work they did breaking secret codes, but what they don’t tell you was where they got the signals from to decode – and I was in that department. There was a little organisation in the Navy, which was called the Y Service, and we listened in to all the signals that the Germans were making and disposed of them according to what was going to happen. – Hilda Hale

I got the Kindle version of this book having already read Sinclair McKay’s The Secret Listeners, also about the Y Service. The focus here is specifically on the Wrens who made up a large part of Y – McKay’s book also dealt with the male and other non-Wren members of the service.

The primary sources for this, as for The Secret Listeners, include many personal memoirs, which enables individual voices to come through. One characteristic that crops up again and again is wry humour, unsurprisingly a common reaction in the face of tension. Daphne Humphrys, remembering the walk back to her lighthouse station at night: “the eerie, lonely walk along the cliff at dark with ‘your tin hat bumping on your back [which] made you think something frightful was close behind you treading. I’m ashamed to say I was often glad to have the sky lit up by an air-raid.’” Her colleague Vivienne Jabez-Smith, at Ventnor, bemoaned that ‘Two Messerschmitts used to strafe the front every morning, once getting somebody's boyfriend in the shoulder and once, much more serious, shattering the display window of the only decent cake shop”. The unfathomable goings-on of military authority were also a rich source of humour; decades later, Wrens from the South Foreland station were still wondering to what end they had been issued orders, in the event of an invasion, to collect a tin of tuna fish and walk to Bristol.

Most of these girls were very young, often still in their teens. They had been recruited for their linguistic skills, since they would have to listen to and understand German radio messages. Many had spent time at German universities or on exchange programmes with German families. So they tended to be from upper or upper middle-class families. Joy Banham, “eighteen and straight from a country grammar school, with a strict nonconformist background” was at first ill at ease with “such people as Dawn Thompson, who had just come back from studying singing in the conservatory at Lisbon, Ann Turner, who had led a sophisticated life in London, and several others with confident, bossy manners and far more experience of the world than her”. They were, however, of an age to adapt to each other and their new circumstances, which was just as well, for they were often in the front line. Some made the voyage to overseas stations – in another example of official thick-headedness, “despite the tell-tale armfuls of tropical uniform, they were told to say that their destination was Scotland”.

Secrecy, indeed, was paramount, so much so that many Navy personnel had no idea what exactly they were doing; nor did the girls’ own families. When the Aguila was torpedoed, with the loss of 22 Wrens en route for Gibraltar, the news was not publicly reported and individual epitaphs for the girls do not mention it. And the bar on mentioning this work lasted a long time after the war, which may be one reason their considerable contribution to the victory was slow to be acknowledged.

Doubtless a dismissive attitude to women also came into play. “Nancy McKinlay was distressed that, having joined the WRNS in the summer of 1941 from Glasgow University with a degree in French and German and having served at several Y stations and in NID24, she was, after her marriage in 1945, discharged as ‘a married woman of low priority’, terminology which infuriated her for the rest of her life.” And at the Chicksands station in Bedforshire, the needs of the Wrens were clearly not a priority: “when the nearby rest hut, containing an Elsan, a bucket-sized portable toilet, was commandeered by the male chargehand as his workshop and office, the women were obliged to carry the Elsan into the field and use it there”.

Its roots in individual testimony render this a lively and absorbing account. There is inevitably some duplication of events and information from McKay’s earlier book but not so much as to be a problem, for the WRNS focus is enough to individualise it. There’s something about the sheer youth of these girls – joining the Wrens because they fancied the tricorne hat, longing for the visiting admiral to accidentally lean against the recently whitewashed wall – that makes the important work they were doing all the more impressive.