The “No Kings” Movement in 1775

Kaitlyn Dunnett/Kathy Lynn Emerson here, today sharing a lesser-known bit of Revolutionary War history.

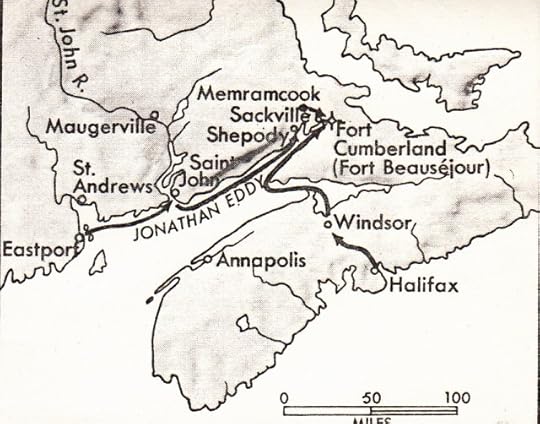

Almost 250 years ago, in August 1775, a group of Nova Scotia men asked General George Washington to send 1000 men, four armed vessels, and eight transports to Windsor, rally local support, and continue on to capture the port of Halifax. Washington rejected the idea on the basis that Nova Scotia (which at that time included present-day New Brunswick) was too remote to hold. Anti-British feeling in the area was high, however, and in February 1776, Jonathan Eddy and fourteen companions left Canada to meet with General Washington in person and try to convince him to change his mind.

They were not successful, but after a brief return home in May, Eddy traveled to Massachusetts in search of military support. This was a logical move. Until 1820, Maine was part of Massachusetts and settlements in Eastport and Machias were relatively close to border towns like Sackville. While Eddy was away, however, 200 British soldiers were sent to Fort Cumberland, which commanded the Isthmus of Chignecto. Pro-revolution leaders were forced to flee by boat to Machias. Their families, including Eddy’s wife and daughter-in-law, were left behind. An expedition to take Fort Cumberland was being planned, but when word leaked out the British sent the Rainbow, two frigates, and an armed brig to attack Machias.

Fort Cumberland

By October, Eddy had gathered eighty men, together with supplies and ammunition, and left Boston for Chignecto. He was joined by enough local men to have a force of 180 when he laid siege to Fort Cumberland. Unfortunately, they were unable to capture the fort before reinforcements from Windsor’s Fort Edward staged a pre-dawn raid on Eddy’s camp, killing some of the rebels and routing the rest. A reward of £200 was offered for Eddy’s capture and a bounty of £100 was placed on John Allen for “exciting rebellion;” Since the British could not find Allen, whose home was seven miles from Fort Cumberland, they set fire to his house with his wife and children still inside.

Mary Allen and her five young children, including seven-month-old George Washington Allen, fled into the woods. They were near starvation and half-frozen by the time her father found them three days later. He was allowed to keep the children, but Mrs. Allen was arrested and imprisoned in Halifax. In June 1777, Allen wrote that many others had been forced from their homes in Cumberland County by “the severe and rigid mandates of the British Tyrant, whose subjects are persecuting the unhappy sufferers with unrelenting malice and fury.” Women with pro-revolutionary sympathies were “kicked when met in the street” and taunted with shouts of “Dam’d rebel bitches and whores.” Allen’s wife, still in custody, repeatedly refused to answer questions about her husband’s whereabouts, saying only that he had gone to “a free country.” When she was finally released, she joined him in Machias.

Jonathan Eddy’s wife and three children were unable to leave Nova Scotia until a special truce was granted in September 1777. At that time there were “a considerable number in the woods . . . waiting for relief from the straits.” Many of those people settled in Maine after the war.

One of the revolutionaries who remained in Nova Scotia, providing information and supplies to his friends in New England, where he had lived until 1766, was Moses Blaisdell. In 1783, he was outlawed for “over acts” against Nova Scotia and he and his extended family, including his son-in-law, Samuel Emerson, were forced to flee. Traveling in small boats, they sailed down the coast at night to avoid capture by British soldiers. They ended up settling on Verona Island in the Penobscot River.

Although Nova Scotians did not succeed in becoming our fourteenth state, a great many of them did end up settling in this country, particularly in Maine. Jonathan Eddy founded Eddington. John Allen settled on Treat’s Island in Passamaquoddy Bay, and Moses Blaisdell’s sons relocated in Thomason, Bucksport, and Orland. One of Samuel and Naomi Blaisdell Emerson’s descendants ended up in Bangor . . . which is why my husband came to be born there.

Kathy Lynn Emerson/Kaitlyn Dunnett has had sixty-four books traditionally published and has self published others. She won the Agatha Award and was an Anthony and Macavity finalist for best mystery nonfiction of 2008 for How to Write Killer Historical Mysteries and was an Agatha Award finalist in 2015 in the best mystery short story category. In 2023 she won the Lea Wait Award for “excellence and achievement” from the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance. She was the Malice Domestic Guest of Honor in 2014. She is currently working on creating new editions of her backlist titles. Her website is www.KathyLynnEmerson.com.

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 509 followers