Teaching in the Age of AI

I’ve been thinking a lot about teaching in the age of Artificial Intelligence. I think all teachers have to now, because our students are clearly using AI applications like ChatGPT to help with their homework — or do their homework. My colleagues have various attitudes toward AI, and have come up with approaches based on those attitudes. Most of them don’t want students to use AI, and explicitly tell students not to use it. But the students do use it — obviously or not so obviously. In response, some teachers have gone back to using paper tests and timed essays handwritten in class. Of course, there are also teachers who are enthusiastic users of AI themselves, and they explicitly incorporate AI into their classes. For example, their students might be asked to write an essay using AI, then revising that essay as a way of learning what sorts of mistakes AI habitually makes and how they can use AI effectively.

I’ve opted for a sort of middle approach, and I thought I would write about it in case my thoughts on this issue might help anyone else. But I’m not sure my approach is the right one. I describe it here in case you find it useful. I will have to evaluate whether it’s useful myself as I continue teaching.

First, let me tell you about my teaching. I’ve taught many things over the years — if you count the classes I taught during graduate school, I’ve been teaching for about twenty years now. My current role is as a teacher of rhetoric, which basically means communication. We start by talking about oral languages, then cover classical oratory, the transition to written systems of communication, the rise of the essay as a literary form, the advent of visual communication in advertising and political propaganda, the invention of photography and film . . . Basically, I take my students from the start of human communication to where we are now, with AI, and then back around to how AI is helping us understand where we all started — with animal languages. It’s a fascinating topic, and one I love to teach because I’m constantly learning, constantly reading up on new theories, new discoveries. Recently, I’ve been reading articles and listening to podcasts on AI. There are new developments every day, and a great deal of disagreement about what AI will do — save the world, destroy it, or a variety of scenarios in between.

My students don’t think about their use of AI so deeply. They see that their friends are using ChatGPT, so they start using it themselves — not all of them, and some students are adamant about not using AI. But some of them are certainly using it, for various purposes. So what have I decided about the student use of AI?

Here’s the policy I adopted earlier this year:

In this course, you may not use generative-AI tools such as ChatGPT to write or revise text in your assignments. Your writing must be your own. You may use AI-based tools to help you understand readings, brainstorm ideas, check grammar and spelling, and assist with translations, as long as the AI tool is not brainstorming, translating, or proofreading instead of you. Even if you use AI to help you understand difficult passages, you are still responsible for reading, completely and with attention, all of the assigned texts.

Then I tell students they must do two things:

Before they use any AI tools, they must (1) watch an article on how AI impacts people in much poorer counties who are paid very small amounts of money to train AI and (2) read an article on how much water AI uses. I want them to be aware of AI’s ecological and societal impact.With their assignment, they must include a note disclosing whether or not they used any AI tools, including grammar checkers and bibliography generators.Do they do these things? The conscientious ones do at least some of them.

My policy goes on to say:

Remember that whatever tools you use to create your assignments, you are the one responsible for turning in thoughtful, interesting, and insightful work. Any errors produced by AI tools that you do not correct will impact the quality of your final draft, and therefore your grade. Use these tools carefully, conscientiously, and ethically, with awareness of their environmental and societal impact.

My goal with this policy is to let students know that they are allowed to use AI (because I think they will use it anyway), but also to make clear that they are responsible for their use of AI. Here is the sort of thing I repeat over the course of the semester:

“Remember that in this class, you’re allowed to use AI, as long as you follow the policy. However, if you’re writing in a way that sounds vague and clichéd and mechanical, you will lose credit, and it doesn’t matter whether ChatGPT wrote it or it’s your own original writing. You need to write in a clear, specific, interesting way, no matter how you do it. You are responsible for your writing. In the end, you will be the one getting a grade, not ChatGPT.”

I also tell them that the worst offenders in terms of mechanical writing — specifically writing flagged by AI checkers — are professors, because so many of them have been taught to write like machines. (This is backed up by research — as well as the experience of colleagues dismayed when they put their own original, carefully researched articles into AI checkers, only to find that it was flagged as almost completely written by AI. This is why I would never use AI checkers for student writing.)

So much for the policy, but what about the actual assignments? I don’t want to go the route of colleagues who are asking students to write on paper. I think that’s a perfectly legitimate route, and it may even be good for students to practice writing manually. I know that I think differently when I write by hand and when I write on a screen. We should not lose what manual writing gives us. But I’ve taken a different approach. Instead, I’ve tried to design assignments that students can’t do by simply plugging them into AI — assignments in which they have to exercise agency and creativity. Here’s an example:

Our first assignment this semester is a photo essay focusing on a specific location. This assignment has a number of steps. First, the students must write a one-paragraph proposal, which I comment on. Then, they must take 10-12 photos and create a storyboard in which they describe both the design elements in each photo (for example, what angle they took the shot from and why) and the sequence in which they want to present their photos. I look at each storyboard and give feedback. Then they must write a draft script for their photo essay, which again I comment on. The final step is to put the photos together with the script to create a photo essay — one that incorporates both text and photos in a way that is more powerful than either the text or photos individually. The photo essay includes a title, captions for the photos, and a Works Cited.

I didn’t design this assignment with AI in mind, but now that we are in the age of AI, here are the basic principles behind this assignment that might help minimize (or at least complicate) student use of AI:

The students can choose which location to focus on (a park, a museum, a market, etc.), and they have to incorporation themselves into the essay (“When I entered Hyde Park, the first thing I noticed was . . .”). They are asked to make choices and incorporate their own experiences and responses. The assignment requires some level of creativity, agency, and introspection.The assignment has a number of steps, and I comment on student work at various stages. At any point, I can say, “This sounds vague–could you be more specific?” or “Could you put more of yourself into this analysis? What did YOU think when you entered the park?” The steps also require students to do different things — propose, analyze, research, synthesize, etc.The assignment has experiential and visual components, so that even if students wanted to plug a prompt into ChatCPT (and they would have to write the prompt, because I don’t provide one — really, their proposal is the prompt), they would still need to visit the location, take the photos, etc. At a minimum, if they were committed to using AI, they would have to use several different AI tools.The assignment does not have a “correct” answer. It asks students to choose a location and show the reader something about that location the reader would not otherwise notice. That could be something about its history, about how it’s used, about the communities that inhabit it . . . So there is no “right” way to do this assignment. It’s about observing, analyzing, researching, and finally revealing.I don’t know if I’m doing this right — it’s possible that a student could do this assignment without going to the location, taking the photos, etc. And the technological landscape is changing so fast that we don’t know how AI will be used, or how we will be teaching, even a year from now. But I offer this as one possible way of thinking about teaching in the age of AI — and I’m eager to learn about what other teachers are doing, at least until we are all replaced by ChatGPT. Which will hopefully not be next year . . .

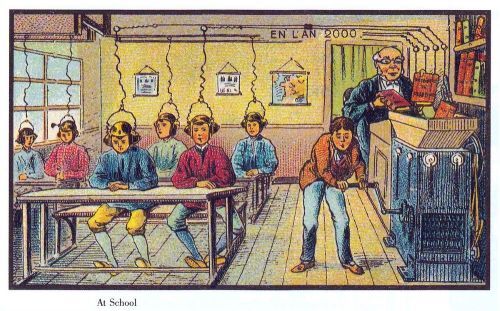

(The image is from In the Year 2000 (En L’An 2000), a French series of postcards produced around 1900 hypothesizing what education would look like in the future.)